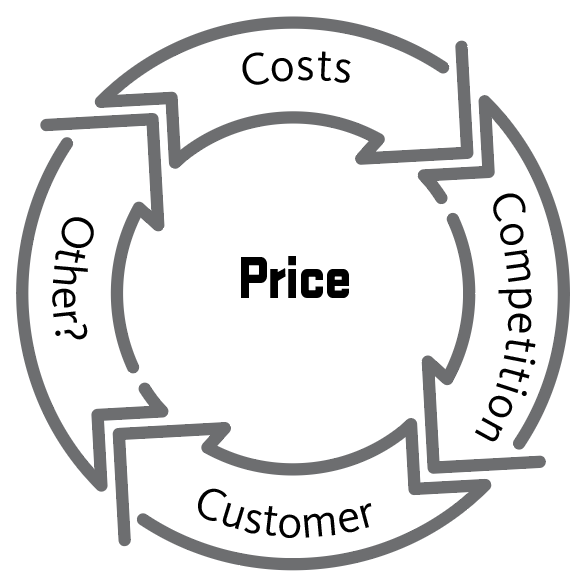

Farmers and ranchers can find it challenging to determine the “right” price for their products. Several variables — including cost of production, competition, customer makeup and season — affect pricing. These variables change regularly. Some are within your control, while others are not.

The more you understand pricing, the more likely your farm business will be profitable. Many farmers don’t know their production cost or their products’ break-even price. They continue to produce and sell based on what they perceive they can charge. Others don’t factor in their own labor when determining profit. It’s also important to remember that in some cases, customers set the prices, while in other cases, prices are up to you.

Pricing decisions are complex. This publication outlines some key considerations that should affect what you charge.

Know your product

Assessing your products and their fit in your market channels is key to setting prices. Do your products have an edge that will command higher prices? Are there better ways to package your products to fit customer needs? Remember that charging the highest price will often not maximize your profit. Here are variables to consider:

Quality

Size, shape, bruises and blemishes factor into pricing. For example, appearance may not be important to customers planning to process produce. You can identify and charge less for seconds (produce items that aren’t attractive enough to be put directly on display). Bagging smaller quantities of products may appeal to parents or single people. When quality varies, post clear signage with pricing tiers.

Quantity

If you have an excess of a product and want to encourage buyers to purchase more, consider offering discounts for bulk purchasing. The more someone buys, the lower the price per unit. For example, you could charge $4 for one pint of raspberries, $22.50 for six pints and $42 for a flat.

Units

Your products can be priced by count, bunch or weight. Think about the demographics of your customers. Since budget shoppers often prefer to know how much a product costs before arriving at the register, consider pricing by unit instead of by weight. Products priced by bunch, count or package don’t need to be calculated and can expedite transactions in crowded markets. On the other hand, tomatoes, apples and other variably sized produce sold by the pound give customers more freedom in choosing how much and what size they want. Providing options can appeal to a diversity of customer preferences. Another common direct marketing practice is to sell products in units other than those commonly used in grocery stores. For example, you can sell eggs in six-packs rather than a dozen. Or, sell flowers by the stem rather than the bouquet.

New and unique products

Keep in mind that having diverse products tends to draw in customers. Think about what products you could add. Recognize the need to provide more education and introduce your customers to new products by offering samples, sharing recipes and telling the product’s story. Novelty items are attractive. Purple carrots, for example, can garner a higher price than orange ones.

Seasonality

Growing in high tunnels will extend your season and allow you to charge more for early and late-season products. When everyone has tomatoes at the market, prices drop. Remember that season extension practices require higher overhead costs than field-grown produce. This will factor in when you’re determining the cost of production.

Bundling

Products that are harder to sell can be packaged with more popular items. Examples include salsa-making kits or gift baskets. Bundling encourages customers to purchase items they wouldn’t otherwise because of the perceived discount.

Know your cost

Knowing and understanding your cost of production in combination with market information provides essential data for determining farm viability in the long run and profitable pricing in the short run. In simple terms, operating a profitable business requires that your revenues (price times quantity sold) exceed your cost of production. This section focuses on your costs, while the next two sections focus on how customers and competition influence the prices you can charge and the revenues you can earn. While the cost of production is always important to you, additional considerations can impact what you decide to charge some of your customers, whether a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) customer or a wholesale buyer.

Determining your costs requires having some key information about the labor and nonlabor inputs that go into producing and selling your products. Collecting data specific to your farm will give you the most useful information. To collect this data, develop record-keeping systems that work for your farm and that you can easily integrate into your day-to-day activities. Start small and be persistent. With a little effort and time, you can collect the information you need to determine your farm’s costs. Suppose you don’t have records that are specific to your farm. In that case, you can refer to published universities and Extension’s enterprise budgets to help you estimate your costs.

Once you have collected the information about different inputs and have assigned a cost to these inputs, it can be helpful to organize your costs. There are two major buckets based on how each cost behaves: variable and fixed.

- Variable costs: When costs are variable, they increase or decrease as you change the number of units (pounds, bunches, count and heads) of a product you produce. Some examples include seeds, fertilizer or labor.

- Fixed costs: When costs are fixed, they stay relatively constant regardless of the quantity of a product you produce. Some examples include property tax, mortgage, rent, insurance and equipment.

At a minimum, the product’s price must be at least equal to the variable cost per unit, or you will lose money on each additional unit sold. To generate a profit, identify the price and quantity combination for a product that will bring in the highest net return.

If you produce multiple products, price each product so that it covers the variable costs. When costs are traceable to an individual product, they are categorized as direct costs. A useful test for determining whether a cost is associated with an individual product is asking whether that cost would be avoided if the product were no longer produced.

In a diversified farm business, there are costs associated with multiple products. Examples include management salaries, business administration costs and liability insurance. When costs are not traceable to any individual product, they are categorized as indirect costs. Both direct costs and indirect costs (also referred to as overhead costs) must be covered for the business to be viable. The question is, how should each individual product be priced so that total indirect costs are covered?

As a starting point for identifying each product’s price and quantity combination, it would be helpful to divvy up total indirect costs and allocate them to individual crops. Farm businesses use many approaches to allocate indirect costs. These include the percentage of space, labor hours, sales and direct costs. There is no one right way to do this. You can choose what works best for you. Once the total indirect fixed costs for the business are covered, any remaining revenue is profit. Predicting the number of products customers will buy at various price points requires knowing your customers and your competition.

If you have dedicated customers such as CSA members, chefs or specialty grocery stores that value your products and production methods, you may be able to use a cost-plus pricing model (covering your costs and providing a reasonable profit).

Let’s look at price-setting situations in which customers and competition must be considered.

Know your customers

A key tenet in determining pricing is understanding who your customers are and what they want.

First things first: Who are your customers? List all the people who currently purchase from you. What products do they buy? How often? In what quantities? What percentage of your overall sales do they represent?

Next: Write down your marketing and financial goals. Do you want to sell more products? Increase the number of vendors you sell to? Increase your profit? All of the above?

If your goals include increasing sales volume, make a list of new potential customers.

Generally speaking, small-scale farmers are more likely to sell directly to the consumer because they can charge higher prices and don’t need a large inventory of products. Consider the pros and cons of these types of market channels:

- Direct to consumer: includes CSA, farmers markets and farm stands

Higher per-unit profit, but typically lower volume of sales. Prices tend to be similar to or higher than shelf prices at the store. Expect to spend significantly more time and energy marketing directly to consumers. - Direct to business: small buyers including caterers, restaurants and co-ops

Lower per-unit profit than retail prices, but the volume of the product may be higher, and you’ll spend less time marketing. Consider offering lower prices for B grade produce, as some small wholesale buyers may be processing the product, and appearance will not be as important. For example, chefs who intend to make soups may purchase B grade produce. - Wholesale to large buyers: includes grocery stores and schools

Lowest per-unit profit. Recognize that grocers need to resell products and will also want a profit. Wholesale distributors offer the lowest prices, but are more likely to purchase larger produce volumes.

Design your pricing strategy with your customers in mind and create pricing tiers accordingly.

Once you determine your ideal customer:

1. Focus on developing relationships

What does your customer value most — personally or in their own business? Examples may include quality, convenience, nutritional value or ecologically sustainable practices. How can you highlight values shared by you and your customers? Examples include pre-orders for busy market customers and CSA newsletters detailing growing practices for ecologically minded members.

2. Research

Customer research is time-consuming but well worth the effort. Consider surveying your market or CSA customers to learn about their values and preferences. How do your retail and wholesale customers want to be contacted? What products do they need in what volume and when? This information will change over time, so be sure to keep current with customer preferences and trends.

3. Use pricing incentives

You can use promotional pricing strategies to market your products and or reward customers for loyalty and bulk buying. Examples include:

- Buy-one-get-one free offers.

- Bulk pricing: incentives for purchasing large volumes.

- Bundling: discounts for purchasing a group of packaged products.

- Loyalty incentive: stamp cards for regular customers.

Know your competition

The final key component to pricing is understanding your competition. When thinking about competition, consider the following questions:

What do your potential customers want?

- Even if you are the only seller of a given product (such as goat meat), you’ll face competition as potential buyers can choose another product or nothing if the price is too high.

- Customers prefer having a choice of suppliers.

- Farmers markets with multiple sellers per product category are more attractive to customers than markets with only a single seller.

- Restaurants and institutions are more likely to commit to local purchases if multiple suppliers are available.

- Bottom line: Competition can be an important part of improving overall market opportunities.

Who is your competition?

- Your competition can be a similar farm or products from elsewhere.

- While customers pay close attention to prices, they also consider quality, display, customer service, convenience and many other factors when making their choices.

- Most market vendors need to watch competitors’ prices because customers can easily compare prices. Farm stands and CSAs have more of a captive audience but should still track the prices offered by others.

How do you stack up? What should you change?

- In comparison to your competition, rate yourself across all attributes that you believe are important to your potential customers.

- If you are new to the market, you may have to set prices at or below the prices offered by competitors.

- Try to avoid “a race to the bottom” when it comes to pricing. Recognize that sometimes competitors will price below what is sustainable for you because they haven’t done their homework or have very different costs than you. In either situation, one option is to discontinue the product.

- You may want to price above the competition if your products offer something extra in terms of:

- Variety (Customers appreciate choice)

- Certifications (such as organic)

- Service (such as help selecting a ripe melon or providing recipes)

- Farm location (Local is a plus, as is a convenient location for a farm stand)

- Diversity of offerings (one-stop shopping)

-

Seek out customer input to direct what you will do going forward

How will your pricing influence your profitability over time?

- Your pricing strategy will influence both immediate and future sales.

- Remember that your pricing strategy will affect how your competitors, including new entrants, price their products.

Remember

There is no “right” price for your products. Determine the price that will best support the success of your farm by factoring in your products, costs, customers and competition. Setting the best prices for your farm products will take time, research and record keeping. Doing that work is an essential part of building a viable farm business.

Additional resources

- More information about the Know Your Cost to Grow program

- Fact Sheet No. 17: Enterprise Budgets, New Entry Sustainable Farming Project

- Farm-direct Marketing: Merchandising and Pricing Strategies, PNW 203

- Recorded OSU Extension webinar and buyer panel: How Much Should I Charge? Pricing Considerations by Market Channel