Each month, the U.S. Department of Agriculture releases state-level data on farmland values through its National Agricultural Statistics Service. Data come from a rotating panel of producers who are asked to estimate the market value of their land. Responses from surveyed farmers are then weighted and extrapolated to generate estimates for entire states.

The survey-based estimates are broken down into four categories of per-acre land values:

- Farm real estate, measuring the value of all land and buildings on the farm.

- Non-irrigated cropland.

- Irrigated cropland.

- Pastureland.

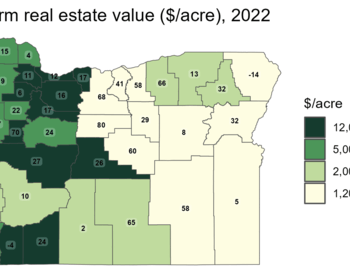

According to the August 2023 report, Oregon's per-acre value of farm real estate is $3,180, representing a $140 (4.61%) increase over the past year (Table 1). This value is in nominal terms, meaning that it is not adjusted for inflation.

| Farm real estate | Non-irrigated cropland | Irrigated cropland | Pastureland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (2023) | 3,180 | 2,600 | 6,600 | 950 |

| Change, 2022-23 | 46 | -81 | 53 | 22 |

| % change, 2022-23 | 1.46 | -3.01 | 0.81 | 2.38 |

| 5-year average, 2019-23 | 3,046 | 2,603 | 6,397 | 909 |

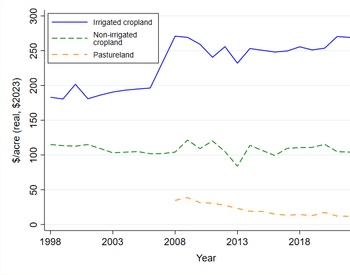

Economists typically examine trends in farmland values over time using real (or inflation-adjusted) values, which account for shifts in values relative to incomes and the prices of other goods.

After adjusting for inflation using the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s Gross Domestic Product Implicit Price Deflator, the change in farm real estate value is more muted but still positive, amounting to a $46 (1.46%) increase in 2023 dollars. When compared to its most recent five-year average, farm real estate values are up $134 (4.41%) (Figure 1). These changes indicate that the value of Oregon’s farm real estate has outpaced inflation in recent years, as it has for many decades.

Non-irrigated cropland value, at $2,600/acre, is down slightly over the past year in real terms, representing a decline of $81 (-3.01%). Compared to its five-year average, the change is a much smaller decline of $3 (-0.11%).

The value of irrigated cropland, on the other hand, is up to $6,600/acre in 2023, a $53 inflation-adjusted gain of 0.81%. Irrigated cropland value is up even more, by $203 (3.18%), relative to its five-year average.

Pastureland value, at $950/acre, experienced the largest gain of any specific land category, increasing by $22 (2.38%) compared to 2022 and $41 (4.49%) against its five-year average.

Despite the recent drop in the real value of non-irrigated cropland over the past year, the values of all categories of Oregon’s farmland have generally more than kept up with inflation in recent history (Figure 2).

Interpretation

With aggregated state-level data on farmland values, it is difficult to tease out any direct cause of the observed trends or year-to-year changes. One clear thing, however, is that the increases in interest rates seen over the past couple of years have not yet translated into large decreases in the value of farmland.

When interest rates go up, we generally expect the value of land to go down. This happens as debt payments for land purchases go up and landowners put a greater discount on the net income they expect to receive from the land in future years.

It is plausible that this is why non-irrigated cropland values have started to come down and growth in overall farm real estate and irrigated values is lower than in the last couple of years. But note that pastureland value growth in 2023 is actually slightly higher than it was over 2021-22.

The contrasting trends between irrigated and non-irrigated land may also be related to the droughts that Oregon, and much of the West, continue to experience, which place a premium on access to irrigation water.

The fact that Oregon’s agricultural land has generally continued to appreciate in value has both pros and cons. Investors tend to be attracted to farmland because it generally keeps pace with inflation, which makes it an attractive and relatively safe asset class. For many reasons, having access to affordable farmland is key for producers, as real estate is the most common source of collateral in farm-related loans.

Without owning farmland, it may be more difficult for producers to obtain the capital, on affordable terms, that allows them to make other investments in their operations. When land values increase, current landowners benefit, but renters and new and beginning producers may find it more difficult to purchase land they need to grow their operations.