Introduction

The northern giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia), previously called the Asian giant hornet, is the world’s largest true hornet, and its predatory habits can devastate honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies. In 2019, the northern giant hornet was detected in British Columbia and northwestern Washington. Two wasps were collected that year, and an additional six were collected in 2020. The northern giant hornet can be easily identified by its massive body size and distinct coloration. However, a few wasp and sawfly species in Oregon are commonly mistaken for the northern giant hornet. Beekeepers should familiarize themselves with identifying and reporting suspected northern giant hornets to mitigate potential spread in the Pacific Northwest.

Native distribution and spread in North America

The northern giant hornet is native to Japan. It is well-established throughout eastern Asia, including Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, India, Nepal and as far as east Russia.

The first detection of the northern giant hornet in North America was in August 2019 in Nanaimo (Vancouver Island, BC), followed by a second report in mid-September in Blaine, Washington. Additional reports in southwestern British Columbia and northwestern Washington suggest that the northern giant hornet could overwinter in these areas. The Washington State Department of Agriculture has current information on the status of the northern giant hornet in the Pacific Northwest.

Distinguishable northern giant hornet characteristics

Worker body size:

- 40 mm (~1.5 in.) body length

- 76 mm (~3 in.) wingspan

- 6 mm (~0.2 in.) barbless sting

Coloration:

- Large yellow/orange head

- Black or brown and yellow-striped abdomen

Identification

There are several large hymenopteran species (i.e., wasps, hornets, bees and sawflies) that are commonly mistaken for the northern giant hornet. So far, most reported sightings of the northern giant hornet have been false. Identifications are made by the Ministry of British Columbia or Washington State Department of Agriculture officials.

Despite their large size and fearful appearance, many commonly mistaken species will not sting people. Some, like elm sawflies, only feed on plants. Others, such as the western cicada killer, the great golden digger wasp or mud daubers, only use their stings to paralyze insect prey.

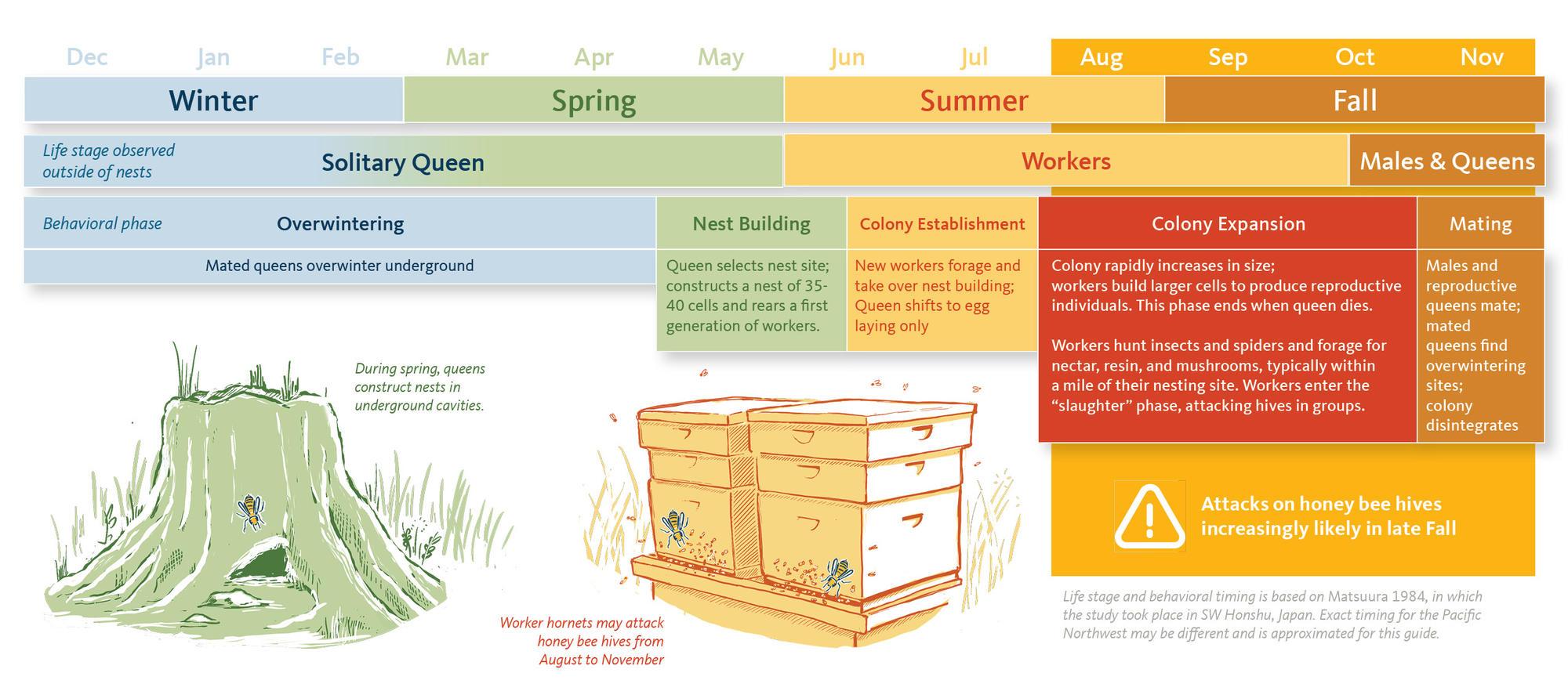

Life cycle

Currently, there is no information about the biology and ecology of the northern giant hornet in North America. Information from Asia indicates that the hornet prefers low mountain lands and forests. Queens mate in late fall and overwinter alone under the soil. They emerge from hibernation in the spring and feed on tree sap while searching for a nesting site. Queens nest in underground cavities and prefer spaces with narrow openings, such as rotting tree roots or abandoned rodent nests. Nests in Japan have infrequently been found in tree hollows 3–6 feet above the ground.

A queen starts building the nest’s framework of comb cells with paper made from mixing her saliva and woody fibers. She lays eggs in these comb cells and feeds developing larvae with tree resin and a chewy paste of insect and spider tissues foraged within a mile of her nesting site. After 40 days, workers emerge and take over foraging and nest building while the queen continues to lay eggs.

Starting in August, the northern giant hornet colony rapidly increases in size and raises males and queens. Males and queens mate very close to their nest near the end of their nesting phase. Once brood rearing ceases, workers and males forage for nectar, tree sap and mushrooms while the newly mated queens find overwintering sites. Nests in Japan typically disband by late October or November.

Japanese beekeepers have developed entrance-mounting hornet traps that protect their bees from late-summer slaughter attacks. There are no reports of honey bee colony deaths related to northern giant hornets in North America. In 2019, there was a report of suspected damage to a honey bee colony, but Washington State Department of Agriculture officials said the report was unconfirmed and lacked documented evidence.

Northern honey bees (Apis cerana), another Apis species, have evolved with northern giant hornets and have behavioral adaptations to protect their hives from northern giant hornet slaughter attacks. If a northern giant hornet enters the hive, northern honey bees can surround and form a “ball” around the hornet. They kill the hornet by vibrating their wings, warming the “ball” cluster and the hornet within it, thus elevating the temperatures at the cluster's center to about 120°F. However, European honey bees (Apis mellifera) are defenseless against slaughter attacks, as they do not possess these defense strategies.

Northern giant hornet and the public

Similar to other stinging social wasps like yellowjackets, northern giant hornet stings can result in a severe allergic response known as anaphylaxis in some people. Hornet stings are more potent than yellowjackets and can cause serious injuries. Beekeepers are the most likely to encounter many northern giant hornets during attacks on their bee colonies. Regular beekeeping suits do not provide sufficient protection, so beekeepers encountering northern giant hornets should not try to kill them but rather contact the Oregon Department of Agriculture immediately. Encounters with northern giant hornets will be less likely for the general public than for beekeepers. Unlike yellowjackets, northern giant hornets are not expected to nest in and around homes in urban areas. They appear more associated with forests or forest fragments. If a nest is discovered, contact the Oregon Department of Agriculture immediately rather than attempt to kill the hornets.

Reporting northern giant hornet sightings

If you are confident that you have seen a northern giant hornet or suspect a northern giant hornet attack on a honey bee colony, please submit a report to the Oregon Department of Agriculture or contact your local Extension agent. Recent modeling from the Washington State Department of Agriculture and Washington State University suggests low winter temperatures and low precipitation make it unlikely that northern giant hornets can establish east of the Cascades.

Report a suspected northern giant hornet sighting to the Oregon Department of Agriculture or call 503-986-4636.

Details to include in a northern giant hornet sighting report:

- Your detailed contact information (name, phone number and e-mail).

- The date and location of the sighting or attack.

- High-resolution photograph of northern giant hornets or suspected predated hive.

- Description of hive damage in case you do not have images from a northern giant hornet attack scene.

CAUTION: Northern giant hornets pose a threat to human health. We urge people to be cautious if they see a suspected northern giant hornet. Do not approach a suspected northern giant hornet, which can sting humans if threatened or disturbed. Do not attempt to remove a suspected northern giant hornet nest.

Trapping for northern giant hornet

Trapping is not recommended at this time in Oregon. Northern giant hornets have not been detected outside of northwest Washington, so northern giant hornet traps in Oregon are more likely to capture other insects that are not a concern. These include beneficial insects. The Washington State Department of Agriculture has launched a trapping program focusing on areas near all confirmed sightings in Washington. In July 2020, Washington trapped the first northern giant hornet in a trap set near Birch Bay in Whatcom County. Commercially available hornet traps will not trap northern giant hornets because the trap entrance is not large enough. However, those traps can be modified to accommodate northern giant hornets.

Recent reports on northern giant hornet sightings

Washington State Department of Agriculture. Reported northern giant hornet sightings.

Washington State Department of Agriculture. Detection data.

References

Matsuura, M. 1984. Comparative biology of the five Japanese species of the genus Vespa (Hymenoptera, Vespidae). Bulletin of the Faculty of Agriculture: 69th Issue. Japan. Mie University.

Matsuura. M., S.F. Sakagami. 1973. A bionomic sketch of the giant hornet Vespa mandarinia, a serious pest for Japanese apiculture. Journal Faculty of Science 19(1): 125–162.

Tripodi, A., T. Hardin. 2020. New Pest Response Guidelines: Vespa mandarinia, Northern giant hornet. U.S. Department of Agriculture — Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

Zhu, G., J.G. Illan, C. Looney, D. Crowder. 2020. Assessing the ecological niche and invasion potential of the northern giant hornet. bioRxiv