Mother Nature throws many obstacles in the path of ranchers, and keeping cows and calves healthy is one of the biggest challenges.

This challenge intensifies when livestock diseases threaten humans. Cryptosporidiosis is one of those diseases.

Cryptosporidium parvum, commonly referred to as crypto, is a group of single-celled intestinal parasites in animals and humans that causes the disease cryptosporidiosis.

Historically, the disease originated from fecal-contaminated drinking water or food. Livestock handlers can contract the disease from ingesting infectious Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts, or immature eggs, from direct contact with fecal material from animals actively shedding these eggs.

Dairy farms at risk

The incidence of bovine crypto diarrhea is higher on dairy farms where confinement and the moist environment is conducive to the spread of these protozoa. However, it is also being identified more often in beef herds in the West. In fact, according to veterinarian Scott Davis, who works throughout central Oregon, crypto in calves is fairly common.

The most common clinical sign of this condition is diarrhea in calves, lambs, and other mammals. People not only experience explosive diarrhea, but also suffer from abdominal cramps, dehydration, headaches, vomiting, fever, malaise and muscle cramps.

If medical attention is not administered, death can occur in severe cases. Children, pregnant women, people with compromised immune systems and the elderly are the most vulnerable and typically have the most severe reaction to this parasite. Unfortunately, there is no commonly advised specific treatment for cryptosporidiosis, and recovery usually depends on the health of your immune system and medical assistance.

North American outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis in humans have primarily been associated with fecal contamination of water supplies. However, this only accounts for 10% of cases reported in the U.S. The source of infection in the rest of these cases is usually unknown, but transmission from animals, particularly Cryptosporidium parvum from calves, is suspected in some cases.

Calves are most commonly infected with Cryptosporidium parvum that can also infect humans. After weaning, calves tend to be infected with other nonzoonotic species of Cryptosporidium that won't spread to humans.

This zoonotic risk poses challenges to humans working with or around 1- to 4-week-old calves. If infected, these animals could potentially transmit Cryptosporidium parvum to people and make them extremely ill.

How humans get sick

Crypto can be passed if a human puts anything in their mouth that has been in contact with the feces of an infected person or animal. Those sickened with crypto often do not suspect contamination from the feces of sick calves and therefore do not know to tell medical personnel of their handling or contact with young calves. This can delay testing for the disease and forestall an accurate diagnosis. Ranchers, dairymen, veterinarian students and others working around young calves need to take precautions against infection.

Cryptosporidium parvum was first described in 1907. Since then, over 30 species of cryptosporidium infecting a wide range of host species have been discovered. There are four species that infect cattle — C. parvum, C. bovis, C. andersoni, and a Cryptosporidium deer-like genotype. Of the four, only Cryptosporidium parvum is a zoonotic disease.

In the early 1970s it was first reported in cattle. At that time, the observed clinical disease could not be solely attributed to Cryptosporidium because there was evidence of coinfection with other viral and bacterial pathogens. In 1983, diarrhea in experimentally infected calves revealed the Cryptosporidium species as a single infective agent. It is now recognized as endemic in cattle worldwide and is one of the most important causes of neonatal enteritis in calves.

Nationally, infections among humans began to rise in the early millennium, but the incidence of the disease has stabilized since 2009. Oregon’s incidence of Cryptosporidium remains twice the national rate (2.6 per 100,000 persons). Cases occur year-round with peaks in August that coincide with increases in exposure to recreational water. Late winter and spring calving season poses a threat to Oregon cattlemen and women as young calves are handled in order to vaccinate, tag and brand. Contact with infected calves during these activities has been blamed for the transmission of Cryptosporidium to ranchers. As it is a communicable disease, human cases must be reported to public health officials.

Adult cows also can be infected

Though neonatal calves less than six weeks of age are most commonly infected with the zoonotic species of Cryptosporidium parvum, adult cows can also be infected. However, adult cows with a healthy immune system may not show any signs of infection. Calves infected with Cryptosporidium parvum can become weak and lethargic and have diarrhea that can be mild or severe in intensity. Feces can contain mucus, blood, or undigested milk. Feces are yellow or pale and watery.

In some cases, persistent diarrhea may result in marked weight loss and emaciation. In most cases, in otherwise healthy calves, the diarrhea is self-limiting after several days.

Cryptosporidium is most infectious when the parasite is passed in feces and then ingested. Infected calves can have crypto in their feces for weeks after they are no longer sick.

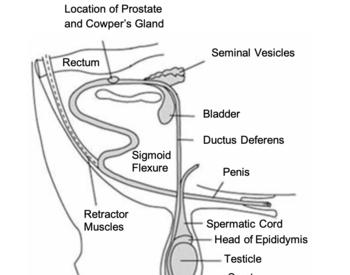

When the immature eggs (oocysts) are ingested, sporozoites are released and invade the cells of the intestines. Infection of cells leads to cell destruction and results in atrophy and fusion of intestinal villi, the finger-like projections extending from the intestinal lumen that are primarily responsible for nutrient absorption. This kind of event can negatively influence the calf’s ability to grow and develop even when it survives the illness.

The risk of infection to humans is substantial as eggs are passed in the manure of infected calves in very large numbers (up to 10 million per gram of manure). During an average infection, a calf may excrete the crypto eggs for six to nine days and shed approximately 40 billion eggs. Simple actions like wiping your mouth with the back of your hand, touching your mouth, or even handling clothes and equipment contaminated with manure and then touching your mouth can spread the parasite. There is some evidence that the infectious oocysts can also be inhaled.

“It’s not unusual for calves to be sickened with a disease and then develop crypto as a secondary disease since immunosuppressed and stressed animals are more susceptible to crypto. In addition, Cryptosporidium parvum can further degrade the calf’s immunity, making the animal at greater risk for coinfection with other diseases,” says Dr. Davis.

No approved treatment

Davis recommends checking for crypto in the feces of sick calves in order to approach treatment in an effective and timely manner. The best way to diagnose Cryptosporidium parvum is to work with your veterinarian and submit a fecal sample to the Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at the Oregon State University, Carlson College of Veterinary Medicine. The lab can run a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that will determine if crypto is present.

There is no effective or approved treatment for cryptosporidiosis in cattle. However, many cases will recover on their own. Sick calves should be housed in a clean, warm and dry environment and receive intensive support. They need fluids to counteract and prevent further dehydration as well as electrolytes to replace fluids lost due to diarrhea.

They also need nutritional support to give them energy to fight disease and repair their bodies. Keeping sick calves hydrated and adequately nourished is critical to a short disease course. Moving unaffected cows and calves to a clean area and away from infected calves will help prevent the spread of disease to other calves. Ranchers should exercise caution when bringing in dairy calves to graft onto beef cows, as dairy calves can be a source of infection.

There is no vaccine commercially available to prevent the disease in cattle and no licensed treatments for sick calves. Good biosecurity and sanitation practices can help limit the duration and spread of the disease. Keeping corrals and livestock pens clean of manure is essential.

Advice for livestock handlers

Crypto eggs have a tough outer shell and are resistant to disinfectants, even chlorine bleach. They can survive outside the body and in the environment for long periods. The eggs can be killed by generous applications of a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution as well as exposure to high temperatures in excess of 160° F, which is hotter than most domestic tap water. Cold temperatures below -4° F will not reliably kill the eggs. The crypto eggs can also be desiccated and killed by completely drying clothes in a hot dryer after washing them.