Transcript

(00:00) Patty Skinkis

This is the High-Res Vineyard Nutrition Podcast Series, devoted to helping the grape and wine industry understand more about how to monitor and manage vineyard health through grapevine nutrition research. I am your host, Dr. Patty Skinkis, Professor and Viticulture Extension Specialist at Oregon State University.

(00:22) Patty Skinkis

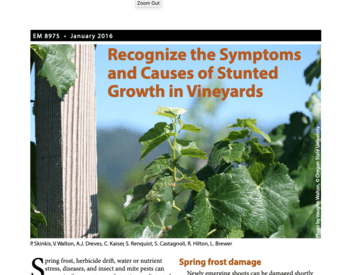

Plant nutrition is important for grapevine health and vineyard productivity. The focus for vineyard nutrient management is on providing adequate mineral nutrients to ensure that we have good fruit set, yield and a healthy canopy to support fruit development to ripeness. However, less is known about the specific role of mineral nutrients on crop quality, particularly for wine grape production. Let’s first start with what we know: nitrogen is important for a healthy fermentation of wine grapes and we can measure must Nitrogen; and it has become a routine measurement in many US wineries. Thresholds for a healthy fermentation were identified about 24 years ago as being about 140 mg/L. However, in practice, there are different views by winemakers about what is ideal, and even for researchers as well, as we’ve done more work on YAN, and the nutrient level is what we need to get coming from grapes going into the winery. Others also quibble about whether supplementing nutrient deficiencies in the winery is easier and a more exact way to control for fermentation quality compared to dealing with it in the vineyard. For potassium (K) , we know that an overabundance can create issues with high must pH. That requires acid adjustments in the winery. However, what about the rest of the mineral nutrients? Do they matter? Or is it really about nitrogen? Is that our main target that we should keep in mind?

Well, to address some of these questions, we have with us today Dr. Amanda Stewart. She’s one of our co-PI’s of the High Resolution Vineyard Nutrition Project. Amanda is an associate professor of enology and fermentation at Virginia Tech. She is leading wine production research in the eastern US where there are field trials being done, most notably studies in Virginia that parallel projects in OR, WA and NY. Her research emphasis is perfect for this study because she has expertise in yeast-assimilable nitrogen (or YAN) and fermentation of grapes and cider apples. She is trained as a biochemist, an agricultural engineer, a food scientist and an enologist, so she is a powerhouse of expertise and knowledge. She received her BS, MS and PhD degrees all from Purdue University--go Boilermakers, also where I got my PhD. She conducts research and teaches courses in enology, fermentation and functional foods.

Thank you for joining us today, Amanda.

(02:47) Amanda Stewart

Glad to be here. Thank you for having me.

(02:49) Patty Skinkis

So, you are the first of our podcast this this season to talk about the wine side of things. We've talked a lot about what's going on in the vineyard, but you're the first one to be talking about what goes on with wine quality as related to mineral nutrition. And much of your work in wine and other fermented beverages and foods has to do with nitrogen. Can you describe the role that nitrogen plays: from what's coming in from the plant to what's going on in the product?

(03:17) Amanda Stewart

Sure. It's a complex role. First and foremost, as you mentioned in the intro, Nitrogen is one of the key mineral nutrients for plants, for life. And, that being said, Nitrogen can be present in proteins which serve both structural and functional roles in plants and in the grape berry, which is what we're looking at when we're making wine. We have, of course, proteins. We also have Nitrogen in other forms like free amino acids, peptides, ammonium ions. Proteins are made up of amino acids, but they're structurally too large to serve as a nutrient source to yeast which is the next step. You know, we've been talking a lot about grapevine nutrition, but in fermentation the next step is the nutrition of the yeast that are going to conduct the fermentation and contribute to the quality of the wine. So, I'm looking at Nitrogen in the grape berry in forms that the yeast can use which include primarily free amino acids and ammonium ions. Maybe some small peptides which are you know, small chains of amino acids, not as big as a protein, but, you know, a couple 3-amino acids as well.

(04:33) Patty Skinkis

So, what forms of Nitrogen are most common in grapes other than in terms of the amino acids? We know that not all of them [amino acids] are in the grape, so can you talk about that a little bit more?

(04:44) Amanda Stewart

Sure, in the grape berry we primarily see arginine and proline as the primary amino acids in varying concentrations, and I say that based on research that has been conducted mostly on Vitis vinifera, or European Wine Grape varieties. So, you know, if you want to look at the diverse genotypes of grape varieties that are being grown around the country, around the world, that may be an oversimplification. I don't know if we can conclude that all grapes are richest in proline and arginine, but the ones we know the most about for wine making definitely are. But that ratio can vary a lot depending on a lot of factors including, but not limited to, the plant genotype, light and dark cycles during the season, rainfall, temperature effects, that can all affect that proline to arginine ratio in addition to the plant genotype.

(05:38) Patty Skinkis

What forms are used most by yeast or other microbes?

(05:42) Amanda Stewart

The forms of nitrogen that are going to be used by the yeast are primarily free amino acids and ammonium ions. These are small compounds that can be taken up by the yeast transported inside the cell and metabolized. A yeast cell is not going to be able to digest protein and utilize that as a nutrient source like a human, or cattle or anything can, so when we look at protein and a lot of crops - soybeans, for example, when we're looking at or when we look at nitrogen in these crops we're looking at protein nutritional value, primarily. But when you come to yeast nutrition, which is what we're concerned with here in the grape berry, we're looking at things that the yeast can use as a food source, which are the smaller compounds like the free amino acids and the ammonium ions that they can readily uptake into the cell and then utilize.

(06:37) Patty Skinkis

The addition of those 2 [ammonia and primary amino acids] are exactly why we call YAN the yeast assimilable nitrogen.

(06:43) Amanda Stewart

Exactly. Exactly

(06:45) Patty Skinkis

So, what happens if there's too much or too little nitrogen?

(06:48) Amanda Stewart

So, one of the primary concerns that winemakers have with too little nitrogen is the evolution of hydrogen sulfide during the fermentation. And this happens as yeast try to compensate for the lack of certain amino acids: pathways are activated that will cause the evolution of hydrogen sulfide which at a very low concentration can have a really negative impact on wine sensory characteristics. You get a smell of like rotten eggs, cabbage, these sulfidic, off-aromas and their related negative sensory impact. So, you know, that's the primary thing that comes up with too little nitrogen. Another thing that can happen is stuck fermentation, slower than ideal fermentation. And with too much nitrogen the primary concern would be that there would be residual nitrogen left over that could lead to microbial instability through promoting unwanted microbial growth after the primary fermentation. Also, with too much nitrogen, some winemakers are seeing a fermentation go faster than they want. You know, with all that being said, these are the general things that I hear from winemakers around these general concepts, around too much or too little nitrogen. However, that being said, I have tasted awesome wines that have been made with 30 mg/L nitrogen - yeast assimilable nitrogen and some starting with 350 mg/L which span far above and beyond that kind of 140 target that you mentioned in the intro. So, I think that the story is probably more complex than just the total YAN value. But those are some general trends and general concerns that winemakers have with too little or too much.

(08:41) Patty Skinkis

Great. Well, some of your research focuses on vineyard and orchard management practices and how they impact fermentations. Have you identified any practices that have a clear impact on fermentation health or product quality that are not related to potential field level impacts of nitrogen?

(08:57) Amanda Stewart

So yes, and I would say that what I'd like to focus on here is diving a little more into the idea that total nitrogen is maybe not the whole story when it comes to product quality or style even, or unique characteristics of sensory characteristics of a product. So, what we've seen in some of the research that I've done along with Greg Peck at Cornell with orchard management for cider apples - we've seen that applying nitrogen both to the soil and in foliar applications can change not only the total yeast assimilable nitrogen in the apple but the amino acid profile that makes up that total YAN. You know, that has also been seen by others working with grapes. I'm looking at that as part of this [Hi Res Vineyard Nutrition] project as well. But the impact of that is something that my lab has looked at with cider apples and fermentation in parallel experiments where we adjust the amino acid profile and look at the impacts of that on fermentation and the cider sensory, and we've seen, even at very low total YAN levels, we've been able to reduce hydrogen sulfide production by adding just a little bit of methionine, for example. And that has been seen by others in wine grape fermentation as well. So, I think there may be more nuance to the total nitrogen requirement than maybe just looking at the total YAN value. Maybe it's worth it to dig in a little more into the amino acid profile and understand how that affects not only product quality and hydrogen sulfide production, but maybe the production of some other interesting sensory impactful compounds as well, like esters. Others have seen boosting the isoleucine, leucine and valine, for example, can boost some of the ester aromas in white wines. So, you know this is something that I think it may not come through in the total nitrogen impact measurements and in plant nitrogen status but may affect the fruit in ways that carry through to wine quality or cider quality.

(11:16) Patty Skinkis

So, most of the trials so far have been nitrogen addition trials? Or have you, have they manipulated nitrogen and in other ways, such as with orchard floor management or vineyard floor management?

(11:28) Amanda Stewart

Sure. In my collaborative work with Cornell, we’ve looked at both soil and foliar nitrogen applications and how that impacts the apple chemistry. What I've done in that project and what I’m doing in this project as well is trying to add value to the horticultural research by maybe digging into a deeper level of nuance on the fruit chemistry and looking at things that might not always be measured in orchard management or a viticulture project but might actually have an impact on the fermentation and the wine quality things like the amino acid profile.

(12:08) Patty Skinkis

That’s a really good point because, like myself, I do vineyard trials and we look just at ammonia and the primary amino acids. We don't go deeper into the individual amino acid profile but we know we're influencing nitrogen in some of the work we do. That's a really good point, I really like that. So, do we know the critical values of nitrogen that is required within a raw product, whether it is wine grapes or apples, that will lead to appropriate levels and types of N in the ferment? I think you got at this before, but how realistic do you think it is to come up with some guidelines around critical values?

(12:45) Amanda Stewart

I think that there are there are several complicating factors to that question. I'm going to answer, not yet. I don't think we have really solid recommendations that can be broadly applied to winemaking in general. I think it's going to depend on factors that interact with the requirements for nitrogen. Others have shown that the lack of biotin or pantothenic acid might influence the YAN requirements to avoid hydrogen sulfide production during fermentation. So, it's a complex system and what we can measure [is] YAN and that's why we want to measure it, we want to track it. But there are other things in the system, other nutrients that could change and influence our need for nitrogen. For example, another thing that I've looked at in cider apples was fungicide residues. So, like post-harvest fruit storage fungicides below the allowable levels. But you know just having a little bit of that there caused negative impacts on fermentation. But those negative impacts could be overcome by boosting the YAN and I believe probably by boosting the cell mass of yeast, though we didn't measure that directly in the experiment. But the fermentation rate sped up, fermentation went to completion with more YAN whereas with low YAN and a little bit of fungicide the situation was different. But that's not something that cider makers or winemakers can measure. But we do develop practices, I think, that lead to kind of the outcomes that we want. We develop empirical practices and sometimes I think we don't realize how many of those practices impact the potential YAN needs, right? So, you have some of the yeast nutrient suppliers who have done some research looking at if we have higher brix, perhaps we need a little bit more YAN. Lower brix, maybe less YAN. Those kind of rules of thumb probably are on the right track but I don't think they've been developed to a high degree of precision yet.

(14:54) Patty Skinkis

Yeah, it takes a lot more research to get at those critical values. I think that's the other thing, is that although a lot of us in research want to come up with critical values to help growers and winemakers, really what we're able to do is provide some guidelines or ballpark. So that's what I like to say: we're getting you in the ballpark so that you know. But in general, it still is good to measure these things and track them. Just like we are encouraging people to take nitrogen or, not just nitrogen, but the plant tissue samples, also collect your YAN data from your must, or from fruit samples if you're a grower. Just to have those pairing to see how they interact because they may not always interact that clearly, like a lot of our data here in Oregon. Whether it's Paul Shriner's or mine, show a very clear link between Veraison time-point, Leaf Blade, Nitrogen and YAN, but it's not always that way. I mean I've seen that in other research projects or vineyards where high vigor, high end but not necessarily high YAN. So, I think getting in the ballpark is what we really can do. You talked about this a little bit earlier but my next question has to do about other aspects of quality beyond just the healthy ferment. So, what role does nitrogen have on other quality-important compounds in wine or other fermented products that you work with?

(16:18) Amanda Stewart

Sure. That's a great question and I think that it's one that is complicated by plant physiology and vineyard management practices . There is some general belief that maybe adding additional or too much nitrogen to the plant might lead to less color in wine, less phenolics in wine, and red wine particularly. The research results on that topic are actually pretty mixed and I think that that can be explained probably by the complexities of vineyard management. If you're adding a lot of nitrogen and the plant’s getting larger and larger and shading the fruit, because of the shading we're going to have less color. You know if there's a lot of canopy management as well as a nitrogen addition, I don't know, maybe that might explain some of the cases where researchers have observed an increase in color or phenolics. Again, it's a very complex system mediated by a lot of factors that happen between putting nitrogen on the soil or the foliar application and harvesting the fruit. It’s a complex system and it's one that's hard to extrapolate broadly from an experiment that was done under a certain set of conditions. But that being said, I think that the main questions that are out there are if we maybe overfertilize looking to boost yield with nitrogen, looking to boost yield, are we going to end up with fruit that's lacking in phenolics, color and other secondary metabolites that impact flavor? We've done a little bit of that with apples. I think the same belief is out there that adding more nitrogen will lead to apples with less polyphenols and that really, recently, has not come out to be true in all cases. I think it was believed for a long time because some good research was done, but under a certain set of conditions. Then when that's tried and people try to apply that broadly under different conditions it doesn't always hold. So, it's a complicated world that we work in with horticultural and food research.

(18:31) Patty Skinkis

I appreciate your comments because I hear that so often, even when we're designing new studies and students are trying to get ready looking at them and we're dealing with a lot of vigor here. Usually pretty good nitrogen levels and we usually are seeing our reduction, or we're trying to reduce nitrogen through our vineyard floor management practices, and we rarely have seen an impact on phenolics related to nitrogen level or based on cropping levels. We've done crop-thinning research, too, and rarely are we making major changes in at least total phenolics that we're looking at. So, it's interesting, and I do think that there's that challenge that we're always trying to break that misunderstanding of nitrogen as being a bad thing or as being, you know, is it really the nitrogen or is it the over-abundance of growth that's really creating a problem? Of course, we know nitrogen plays into that but it's not the only culprit for creating imbalance. So, are there any other nutrients that you think have a clear link to fermentation that are worth exploring, beyond the macronutrients?

(19:35) Amanda Stewart

Oh, sure. Definitely. I think that one that we're looking at in this project, beyond nitrogen is potassium. That's important in wine quality, especially red wine quality, in the role that potassium can play in buffering the pH. So, you may end up with high acid and high pH which is a bad combination in terms of effects on microbial ecology and microbial stability in the juice or the wine that follows. So, that's another one that is of great interest in this project.

(20:09) Patty Skinkis

Do you think that there's any link with any of the micronutrients? I know that there's not much research out there on this topic, but do you think that there is any reason for us to think that there would be any major link, or maybe even minor successful link? Because I know there's a lot of growers and possibly listeners out there who are supplementing with a lot of micros [micronutrients] and we just don't know how much they're helping the plant, let alone the wine quality.

(20:39) Amanda Stewart

Interesting, Interesting. Are you thinking like in terms of like zinc, calcium, things like that?

(20:46) Patty Skinkis

Exactly. So, a lot of growers will tell me that they're applying calcium in hopes of, especially here in western Oregon, hoping with like the structure of the cell, and then they think that will help with maintaining compounds in the fruit. I don't think we have good data out there. Well, I know we don't have good data out there to support that. But, you know, all of these other things that kind of are being used, and maybe they're being just used or grabbed from other cropping systems or other applications and being applied to grapes in hope of improving quality. But do you think there's any link that you could think of from a wine production standpoint that might be even possible? Or is it just too unknown at this point?

(21:31) Amanda Stewart

I feel like that's one that there's a lot of literature out there on, like zinc and fermentation with beer, things like that. But usually, it's on the end of a lack of a key micronutrient that the yeast needs to grow and multiply and reproduce and metabolize. With wine grapes I don't think we're at the threshold typically under normal production conditions to be at a lack of the requirement that yeast have for those micronutrients. So, unless it's potentially something on the plant side or plant health side, berry structural quality, like you mentioned- I don't know, I haven't heard anything like that and I haven't heard that question coming into wine fermentation research to the degree that it does in brewing, where you're getting those things in the water.

(22:28) Patty Skinkis

Interesting. Can you describe some of the research projects that you have planned within the High-Res Vineyard Nutrition Project? We know that we added crop quality to the project, and we have different crops. We've got our different target markets for the grapes. We all have grapes, but we have wine and we have table grapes, but you're really our lead oenologist with Jim Harbertson as well on the project. So, can you describe some of the work that you're doing in Virginia and possibly elsewhere?

(22:57) Amanda Stewart

Sure thing. In the first year that I've got a graduate student working on this we're partnering with Dana Acimovic, our viticulturist here in Virginia, looking at Chardonel from her field nitrogen application studies. She's got six conditions that involve soil and foliar applications of nitrogen, and we were able to get enough fruit from those research plots to make small lots of Chardonel [wine] without modification but using two different yeast strains. We've got enough to do sensory by sorting task, so we will use untrained panelists and look at how they group the wines made from these different treatments as well as the yeast strain treatment that we overlaid and see how much sensory difference we can detect here, based on going all the way back to those field applications of nitrogen. I think, I want to start there because I think that if we can't tell a difference sensorially in the wines, then perhaps the nuance of chemical difference we may be able to detect is not so impactful when it comes to wine quality. So, I'm excited that we have a great partner here at Virginia Tech, Dr. Jacob Lawn, who's been developing and piloting novel rapid methods for sensory on craft fermented beverages including beer, wine, cider, we’ve done some chocolate, too. So, these methods are good for getting the gist of the impact and the extent to which some of our treatments can impact sensory characteristics of the products. So, we'll get that data in the spring, and what I'd like to see is a theme that's come through in my research in the past is always trying to compare the yeast strain impact versus the yeast nutrient or nitrogen modification impact. So, sometimes we see that the nitrogen status in the must or the juice can impact the sensory quality of the wine, but maybe the yeast strain choice has a bigger impact, and that's okay, but it's good to know the relative impact of those treatments, and I think through this experiment we'll be able to assess that. We're also measuring the amino acid profiles in juice harvested from all of these field, soil and foliar nitrogen application treatments. So, we'll also be able to pair the amino acid profile and total YAN data with the sensory outcomes. Through that comparison, we hope to identify, or we’d like to identify differences in amino acid profile that might be more likely to lead to sensory impacts under these conditions that we fermented them under which are relevant to commercial production conditions. So if we can see what amino acids potentially are impacting that, then we can do some parallel experiments to what viticulturists are doing in the field where we would modify the amino acids here in in our pilot winery and see what impact we can have on that and perhaps think about not only potential targets for berry nitrogen but also yeast nutrient product development ideas potentially as well that can help winemakers have an additional tool, maybe to use nutrients that are going to help them achieve their style, not only just boost the YAN. I think that this also complements some work that I know Paul Schreiner has recently completed looking at Chardonnay and finding that depending on whether that nitrogen was applied in the field to the soil or foliar application, or if it was applied in the winery in the form of diammonium phosphate or an organic nitrogen supplement, they got different sensory outcomes with similar starting total YANs before fermentation. So, I would hypothesize that some of those differences could be attributed to the amino acid profiles that made up those total YAN values, and we'd like to dig into that question a little more through this project.

(27:08) Patty Skinkis

That's really exciting - the idea of digging in deeper and I like that the work will come out with outcomes for possibly in the vineyard and the winery. Like you said, product development. If we can't control everything in the vineyard with how we're doing things but in the winery you’re able to adjust your amino acid composition, so that's fantastic. I really like the thought process behind it and I really like that the work’s being done in a hybrid variety, or I guess sometimes people don't like them being known as hybrid. You know, as researchers we call them “hybrids” or we should call them “cool climate” or “cold climate” varieties or “alternative varieties.” but Chardonel is one of those for any of those listeners out there who aren't familiar with Chardonel. I'm glad that we're doing some of the research on the East Coast as well as out here on the West Coast.

So, my next question is a fun question for you. What is your favorite grape to work with before it's made into wine? What is your favorite grape and also, what is your favorite wine?

(28:10) Amanda Stewart

Oh, I've had a lot of feelings about grapes that I've worked with over the years, and I'd say my favorite grapes to work with are the ones that come into the winery in good condition. Grapes that are well adapted to the climate they're being grown in, they're well taken care of, they're harvested at the right time. That's my favorite grape to work with.

(28:29) Patty Skinkis

A practical answer for somebody who makes wine. I love it.

(28:32) Amanda Stewart

And [from someone] who used to be an engineer, right?

(28:35) Patty Skinkis

That’s right, because we can't control everything—the fewer mistakes made [in the fruit] makes it easier to make wine. That’s fantastic! What about your favorite wine? Do you have a favorite wine or wine style?

(28:47) Amanda Stewart

Oh my gosh, this is such a loaded question.

(28:52) Patty Skinkis

Don't worry. We all feel this way when we're asked this question.

(28:56) Amanda Stewart

Ah, right? Again, I think it's the wine that's right for the place it was grown in. When I worked in Oregon, you know, so many wonderful pinot noirs coming from the Midwest, amazing hybrid wines made from hybrid grapes and here in Virginia we've got amazing reds and whites. I think we're in a sweet spot for production of a lot of both European grapes and hybrid grapes here. So, I don't want to hedge too much on that question, but that is a tough question. To specify a wine variety or a cultivar. Maybe that's why I'm doing this - I'm still trying to figure that out and there's so much diversity out there. So many interesting wines and interesting stories behind how these wines are made and interesting questions to answer about how they can be made best.

(29:49) Patty Skinkis

Yep, absolutely! Well, thank you for joining us today, Amanda. And those of you listening, thank you for joining us. To learn more about the High-Resolution Vineyard Nutrition Project, see our web site at highresvineyardnutrition.com.

Vineyard nutrient management often focuses on nitrogen which is important for berry and must nitrogen that feed the fermentation. However, there is more that we need to learn about nitrogen in wine. In this episode, Dr. Amanda Stewart, Associate professor in the Department of Food Science and Technology at Virginia Tech, talks about her research to understand the components of nitrogen that lead to sensory impacts in wine and ciders.