Whether you’re growing hay for market or providing forage for livestock, a healthy pasture maintains healthy soil, produces high yields, excludes weeds and has a positive impact on the environment. Proper management — more than any amount of fertilizer, seed, water or herbicide — is the key to a healthy pasture.

Begin by taking a good look at the soil beneath your pasture.

Improve or preserve soil health

- Know what’s in your soil. Conduct soil tests every two to three years to guide your fertilizer applications so you are not over- or underapplying amendments. Applying too much fertilizer can lead to nutrient pollution in streams. Too little can limit forage production and quality. Both over- and underapplication can waste money.

- Manage soil fertility to your objectives. Pastures that are well-managed and grazed by livestock recycle nutrients efficiently, while harvesting hay will remove nutrients from your soils. Adding sulfur and phosphorus can increase the amount of legumes in some pastures. Adding nitrogen will increase grass hay yield. Adding organic matter will improve the water-holding capacity of your pasture and boost nutrient supply.

- Know your soil type. Use soil survey tools listed in “References,” page 4, or see other publications in this series to learn about your soil texture, rooting depth, potential productivity and other information.

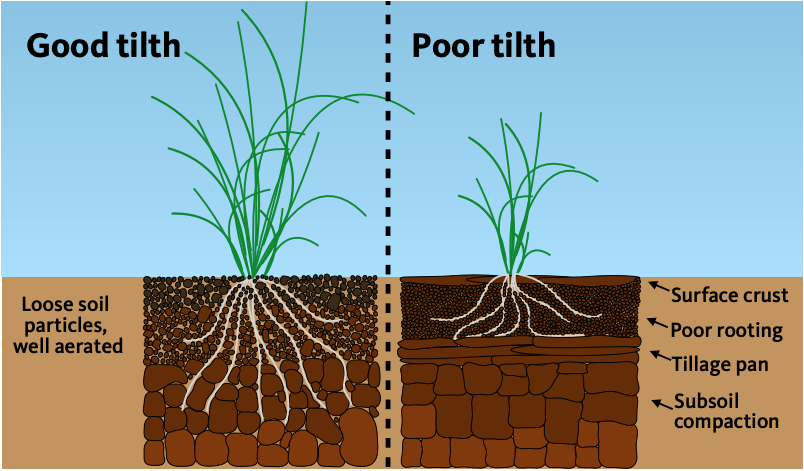

- Avoid grazing and machinery traffic on wet soils. Wet soils are susceptible to compaction, which makes it harder for grasses to grow. Move animals to hardened or better drained pastures when soils are wet.

Manage forage production, grazing and hay harvest

Perennial grasslands have an important role in our landscape. In addition to providing low-cost feed for livestock, healthy pastures and hayfields can help to improve water quality, reduce erosion and provide wildlife habitat.

- Use rotational grazing practices. Rotational grazing means moving livestock to different areas of a pasture to prevent overgrazing. This strategy allows pasture plants to recover and grow after grazing. Rotational grazing practices can increase forage yields, reduce weedy competition, improve soil health, and minimize erosion and pollution. Divide your pasture into relatively equally spaced paddocks and move livestock from one paddock to the next to allow for controlled management of forage removal and regrowth.

- Monitor forage height. Do not graze your pastures much lower than 4 inches, and wait to graze until 8 inches have regrown. “In at 8 inches, out at 4 inches” is the rule of thumb for most common Oregon pasture grass species. Many irrigated pasture grasses grow more slowly in summer than in spring, so base your grazing or mowing schedule on the height of the plant rather than by some calendar date. Pastures that grow to exceed 12 inches could be taken out of the grazing rotation and harvested for hay.

- Document your management by recording the dates you move animals into and out of pastures. Records of pasture quality and weed abundance can also be helpful. Measure forage yields using the clip and weigh method, grazing sticks and visual assessments. (See “References,” page 4.) Record the rotation length and livestock type and numbers. Documenting this information will reveal whether the pasture is improving or declining over time and allow you to make management adjustments without relying on memory alone.

- Seed only when necessary. Good grazing management can improve the growth of many pastures, but sometimes few or even no desirable forage plants are present. In these cases it might make sense to reseed. Use low-impact planting methods such as broadcast seeding of legumes and a no-till drill seeder. Replanting large areas of pasture can be risky, and can take a pasture out of production for more than a year. Successful establishment depends on appropriate weather and limited weed competition.

Use integrated pest management to fight weeds

Weeds are opportunistic, and forage plants are competitive. Maintaining a thick and vigorous pasture is the best defense against weeds. Grasses tolerate repeated grazing, while many weeds do not.

- Ensure adequate soil fertility and uniform irrigation coverage to prevent weeds from taking hold.

- Know your weeds. Being able to correctly identify weeds and understand their biology is the key to integrated pest management. The only way to know if you’re choosing the best combination of tools is to understand how specific weeds grow and to target weak points in their life cycles.

- Apply herbicides judiciously and follow the label. Herbicides, like all management tools, have potential risks in addition to their benefits.

- Develop an integrated pest management strategy. Rather than relying on a single tool to manage weeds, combine several practices such as mowing, tillage, hand-pulling, grazing, fire, fertilization and herbicides. The goal of an IPM approach is to use a combination of methods to manage pests or weeds by the most economical means — and with the least possible hazard to people, property and the environment.

| Traditional pest management | IPM | |

|---|---|---|

| Program strategy | Reactive | Preventative |

| User education | Minimal | Extensive |

| Potential liability | High | Low |

| Emphasis | Routine pesticide application | Pesticides are used when alternate methods are inadequate |

| Inspection and monitoring | Minimal | Extensive |

| Pesticide application frequency | By schedule | By need |

| Pesticide application target | Areawide spraying | Spot treatment |

Protect environmental resources

Take steps to protect waterways and wildlife.

- Minimize livestock damage to streams. Livestock can damage riparian areas if left unmanaged. Use fencing, hardened crossings, culverts and off-channel watering facilities to control access. Refer to other publications in this series for additional information on managing these areas.

- Consider the impact to wildlife in your land management decisions. Many types of wildlife — from rodents and birds to deer, elk and bear — can be drawn to your property. Create fencerows for shelter and habitat, use wildlife-friendly fencing, and keep key areas of your land undisturbed to provide habitat for wildlife. Limit mowing to those periods outside of nesting and rearing seasons. See Wildlife Habitat: Nurturing a Diverse Mix of Flora and Fauna, EM 9250.

Follow the rules

Oregon’s Agricultural Water Quality Management Act helps farmers and ranchers address water pollution regulated under the Clean Water Act. The act bars agricultural practices from polluting waterways.

The Agricultural Water Quality Management Area Plan describes various types of pollution potentially caused by agricultural practices. The plan does not dictate to agricultural producers how to manage their land to prevent water pollution, but instead offers a suite of best practices to address potential water pollution concerns that could result from agricultural production. Contact your local Soil and Water Conservation District for information on this plan.

Video resources

- South Dakota State University Extension, Clip and Weigh Method

- Noble Research Institute, Using a Grazing Stick to Determine Stocking Rates on Small Grains Winter Pasture

References

- AgriMet station information and links

- National Resources Conservation Service guide to basic infiltration tests

- Oregon State University Extension Service pasture resources

- Oregon State University Extension Service, Pasture and Grazing Management in the Northwest, PNW 614

- University of California, Davis, Guide to integrated pest management

- University of California, Davis, Soil Research Lab — SoilWeb Apps

- University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service, Determining Soil Texture By Feel

About the Rural Resource Guidelines

This is one of a series developed for private landowners by the Land Steward Program of Oregon State University’s Southern Oregon Research and Extension Center. This guide covers general terms and helps users assess resources and manage property in a responsible manner. This guide was developed for use in Jackson and Josephine counties but is applicable to other areas.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, under award number EW18-015 through the Western Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program. USDA is an equal opportunity employer and service provider. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

This series was developed by the Oregon State University Land Steward working group: Rachel Werling, Land Steward coordinator; Max Bennett, Extension Forestry and Natural Resources faculty and associate professor; Clint Nichols, rural planner, Jackson County Soil and Water Conservation Service; and Land Stewards Stan Dean, Jack Duggan, Don Goheen, Scott Goode and Cat Kizer.