We see them at the edges of farm fields or along roads: long rows of trees, shrubs, flowers and grasses known as hedgerows. They are living fences with the ability to grow food, shelter wildlife, save water, manage weeds and look beautiful all year round.

Hedgerows are sometimes called shelter belts, windbreaks or conservation buffers. These layers of plant life enhance the beauty, productivity and biodiversity of a landscape.

Hedgerows originated in medieval Europe and are enjoying a modern resurgence. People in England planted hawthorn cuttings and allowed them to grow about 6 feet. They were bent and trained to fill gaps in the trees, yielding a living fence. They called these fences "hagas" or hedges, form the word "hawthorn." As the birds settled in the hawthorns and dropped seeds. more plants sprung up. Today, many farms in England are surrounded by ancient hedgerows that shelter beneficial organisms and conserve soil and water.

Hedgerow plantings were uncommon in the early United States. In the 1930s, the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Shelterbelt Program briefly supported planting trees for windbreaks to prevent soil erosion in the Midwest. Today, as interest surges in sustainable farming methods, more people are turning to this age-old practice.

Hedgerows can serve several ecological functions. Among their many benefits, hedgerows:

- Enhance ecological biodiversity.

- Offer food for livestock, humans and wildlife.

- Provide habitat for beneficial insects and pollinators.

- Facilitate water conservation.

- Provide windbreaks.

- Help manage invasive weeds.

- Provide erosion control and improve soil health.

- Support the health of aquatic habitats.

- Enhance carbon sequestration.

- Create borders and privacy screens.

- Reduce noise, dust, chemical drift and other types of pollution.

- Diversify farm income.

- Generate year-round beauty.

Let's look at these benefits in detail.

Benefits of hedgerows

Enhance ecological biodiversity

Biodiversity describes the variety of life forms within a specific ecosystem and the relationship of these organisms to one another and the broader environment. Hedgerows can be designed to attract a wide variety of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, insects and plants, many of which offer beneficial relationships to each other. They also create more edges, or “ecotones,” between different habitats, which increases species diversity. Trees and shrubs provide shelter for larger mammals, and nesting sites and perches for raptors, which are important predators of rodents. Dense or thorny shrub thickets can offer songbirds a refuge to escape predators as well as a place to nest. The diverse composition and structure of a hedgerow creates a functional habitat where species experience vital interconnections with one another and the environment.

Offer food for livestock, humans and wildlife

Hedgerows provide undisturbed refuge for species of all kinds, creating wildlife corridors, travel lanes or habitat islands. Hedgerows help protect wildlife from predators and provide sheltered access to riparian zones or other water sources. These corridors are especially important in fragmented landscapes, such as fields where only a single crop is grown. Hedgerows provide shade to reduce heat stress and help to block wind currents. These measures support a healthier wildlife population. Berry-producing plants encourage insectivores, such as birds, that also prey upon common crop pests. The hedgerow habitat creates cover for wildlife so they can feed, nest and care for their young.

Provide habitat for beneficial insects and pollinators

Planting a variety of flowering trees, shrubs, forbs and perennial plants provides insect habitat, and nectar and pollen sources throughout the year for beneficial insects and pollinators. Plants in the family Umbelliferae attract parasitic wasps; predator flies such as hover flies, lacewings and ladybeetles; and true bugs, like ambush or minute pirate bugs. Flowering plants in this family include coriander, dill, fennel, parsnip, parsley and carrots. These plants are useful in the kitchen and are also very attractive to pollinators. Over 75% of successful production of food requires pollination. Increasing plant habitat for pollinator species improves fruit set, size and quality, as well as general biodiversity. Pollinator habitat also attracts beneficial insects, which prey on many crop pests. Increasing the numbers of beneficial insects can help farmers manage crop pests and cut down on insecticide use.

Facilitate water conservation

Hedgerows retain water and reduce evaporation by reducing wind speed and providing cover over the ground surface. Plants also catch and store water in their root systems, leaves and branches, slowing the rate of excess rainwater entering waterways and reducing the risk of flooding. Decaying matter from the roots, stems and branches of hedgerow plants increase the organic matter in the soil over time. This increases the soil’s ability to absorb and retain water. Planting hedgerows on hillsides helps conserve water and soil by reducing erosion. If planting near adjacent cropland, periodic root pruning can reduce competition for nutrients and water.

Provide windbreaks

Properly designed hedgerows can reduce wind speed by as much as 75% and improve crop performance. This is especially effective when plantings reach a density of 40%–50% and are planted perpendicular to the prevailing wind. Wind-resistant trees usually have flexible, wide-spreading, strong branches and low centers of gravity. Wind-tolerant shrubs often have small, thick or waxy leaves or very narrow leaves or needles, to help control moisture loss. Wind can disturb pollination and damage fruit and flowers when plant parts thrash against each other. During times when soil is exposed, a windbreak can protect topsoil from erosion. Crops under wind stress also put energy into growing stronger roots and stems, resulting in smaller yields and delayed maturity. Strong winds also cause lodging of grain and grass crops, bending the stems and making harvest more difficult. Winds dry out crops on the field edges, increasing pests such as two-spotted spider mites.

Help manage invasive weeds

Hedgerows planted along roads or between crop fields may prevent weed seeds from blowing into the field. The weed seed pods collect on hedgerow plants, where a farmer could remove and burn them. Hedges can prevent millions of weed seeds from entering the crop field. As hedgerows mature, these plantings displace invasive weeds. If well maintained, this weed management lasts the lifetime of the hedgerow.

Provide erosion control and improve soil health

Rain, irrigation, clean cultivation and vacant field borders can all increase erosion potential in an agricultural system.

Hedgerow plantings can significantly reduce the amount of soil erosion on a landscape. They can also provide a barrier to filter out pollutants, such as pesticides, and slow down sediments and organic material that can flow from farm fields into waterways. This is accomplished by increasing the surface water infiltration rate and improving soil structure around the root zone. This, in turn, decreases fertilizer runoff from farm fields. The biomass that plants shed acts as a soil conditioner and can enhance plant growth. In urban or suburban environments, hedges similarly reduce pollutants from neighboring sites.

Support aquatic habitat

Hedgerows can provide shade to riparian areas. Shade reduces water temperatures, prevents water evaporation and improves watershed quality. Though many factors influence watershed temperatures, studies have proven that lowland streams bordered by trees and tall shrubs exhibit cooler temperatures. The hedgerow’s latitude, stream aspect, leaf density and the height of its vegetation from the water surface all affect water temperature.

Enhance carbon sequestration

During photosynthesis, trees, shrubs and grasses absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, allowing the carbon to become part of the plant’s tissue. As plants die or shed tissue — either through natural processes or pruning — the carbon that was stored in the plant breaks down and enters the soil. Plants store relatively large amounts of carbon in their biomass, helping to offset some of the effects of climate change. A tree can absorb as much as

48 pounds of carbon dioxide per year and can sequester, or store, 1 ton of carbon dioxide by the time it reaches 40 years old.

Create borders and privacy screens along roads and between properties

Hedgerows are attractive borders and can block undesirable views. Evergreens offer year-round screening. When selecting plants, consider the height at maturity for optimum screening. Evergreens can be pruned to control height and density. Plant a diverse mix of species to help protect against damage from a single pest or disease.

Reduce noise, dust, chemical drift and other types of pollution

As hedgerows mature and become dense, they can create barriers to reduce noise, dust, chemical drift and other pollutants. Open canopy trees are effective barriers to dust and pesticides; air and particles slowly filter through them instead of depositing clouds of pollutants on the other side of the hedge.

Plant hedges as close as possible to any areas where pollutants are a concern. This can help alleviate neighborhood conflicts where agriculture intersects with urban areas.

Hedgerows can act to contain contaminants from urban or suburban environments and keep them from entering agricultural areas.

Diversify farm income

Trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants in a hedgerow can also serve as sources of income. Potential products include nuts, fruits, berries, leaves, flowers, seeds, bark and medicinal herbs. You can grow plants to be propagated as seeds, rootstock, cuttings and transplants. Other potential crops are nursery stock and floral materials, including ferns, broadleaf evergreens, flowers and willows grown for craft material and furniture. You can grow fruits, berries and nuts for food. Hedgerows can shelter bees and encourage a higher pollination rate. Consider planting trees for secondary wood products such as lumber, veneer, firewood, chips for bedding and mulch. Game birds such as quail, pheasant and sage grouse are attracted to hedgerows. Managed hunting can provide a potential source of food and off-season revenue for landowners.

Generate year-round beauty

Hedgerows in the landscape add continuous beauty. You can design a hedge for year-round interest, considering the color and texture of leaves and bark, bloom color and timing, and the general growth habit or form of plants.

Establishing and maintaining hedgerows

Whether in rural or urban settings, the principles of planning a hedgerow are the same: Evaluate the site, determine what you would like to accomplish with the plantings, match the right plant with the right place, and properly prepare the site.

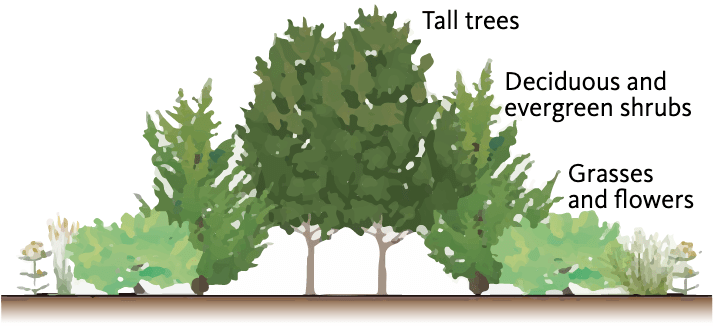

Design

There are many essential components to consider when designing a multifunctional hedgerow. The first step is to observe the site where the hedge is to be planted and take into consideration the ecological and environmental conditions listed below. These elements influence the design, plant selection, location and the size of the area to be planted. Although a single line of trees will provide some benefits, four or more rows of plants are optimal for windbreaks, water and soil conservation, wildlife habitat and general biodiversity. When it works for the situation, place plants tallest at maturity in the center row, with shorter ones inter-planted between and along the edges. A diverse selection of plant sizes and characteristics is most beneficial. When possible, orient rows perpendicular to prevailing winds.

Hedgerows following land contours create meandering lines on the landscape, producing a natural appearance and larger buffer for wildlife habitat. If the goal is to attract pollinator species, reserve approximately one half-acre for every 40 acres planted in crops.

Plant selection

Plant a wide variety of multi-tiered plants for maximum habitat. Avoid varieties that are susceptible to common pests and diseases and choose plants that are non-invasive. Some perennial species such as blackberry can provide excellent wildlife habitat and food crops but are highly invasive and require frequent maintenance. See the plant lists on page 7 for plantings suited to the Pacific Northwest.

When selecting plants, consider the conditions plants need to survive in specific habitats:

- Range: place of origin (indigenous, native/non-native).

- Hardiness zones: frost dates.

- Light requirements: sun or shade.

- Size of plants at maturity, growth.

- Soil type (pH, fertility, erosion concerns).

- Drainage.

- Water movement and moisture needs.

- Planting time.

- Bloom time: seasonal interest.

- Day length.

- Productivity.

- Tolerance to heat, cold, salt, drought, pollution, wind and wild or domestic animals.

- Evergreen or deciduous.

- Plant structure: form or shape, texture, leaf and bark type.

- Edible or poisonous: what parts.

- Insect and disease resistance.

- Plant size, costs and availability.

- Maintenance needed.

- Allellopathy: a chemical inhibitor of one plant to another which can impact germination or plant growth.

Ultimately, place plants together that have similar soil, water, sun and drainage needs.

General planting recommendations:

- Plant trees and shrubs about 6 to 8 feet apart in rows 8 to 10 feet apart.

- Plant one or two rows of tall trees flanked by a row or two of shrubs. A 20-foot wide hedgerow can have two rows of shrubs flanking a row of trees.

- Hedgerows work best for wildlife when they are wider than 20 feet.

- Depending on the site’s prevailing winds, a winter windbreak could have at least two rows of evergreen trees and a row of deciduous trees or shrubs. A summer windbreak could have at least one row of tall deciduous trees and a row of deciduous shrubs.

- Make sure the planting holes are deep and wide enough to accept and cover the roots of each plant. Be sure to water in each new planting.

- In a small area, place a 3-inch layer of straw mulch or cardboard around each tree and shrub after planting to discourage weeds and encourage plant survival.

Soil preparation

Soil preparation is one of the keys to plant survival. On a smaller site, an easy way to establish planting areas in existing grass or pasture is to apply a thin layer of compost or manure, followed by several layers of cardboard, and mulch such as straw or leaves. Worms are attracted to the manure and will work over the winter to decompose grasses and fertilize the soil. However, this method may not be practical on a large scale. In this instance, prepare the area for planting by tilling the ground in spring and planting an early cover crop such as crimson clover, followed by buckwheat. In late summer, till or disc in the cover crop and replant an overwintering cover crop such as crimson clover, field peas or vetch. Cover crops improve soil fertility, reduce weeds, stabilize the soil and attract beneficial insects. Till again the following spring and install the first set of plantings for the hedgerow.

Another option for sites with high weed pressure is solarization. Closely mow the ground and put down UV-stabilized anti-condensation greenhouse plastic in midsummer for several weeks to kill the weeds. After solarization, remove the plastic and follow with a fall planting.

Planting time

In more temperate environments, fall planting allows roots to become established before foliage emerges and gives plants the benefit of winter rains. In extreme cold climates, early spring may be the ideal time for planting. At the time of planting, apply amendments such as compost or manure as a top dressing.

Irrigation

To increase the success rate of your hedgerow planting, provide supplemental water for the first two or three years. Irrigate once a week during the heat of the summer during the first year. For the second year, water every two weeks. In the third year, irrigate once a month. Irrigation needs depend on the location and the plants selected. Be sure to water deeply to encourage deep root growth. Most hedgerow plantings may not survive if they do not get supplemental water in the first few years. Water can be supplied by swales, furrows, flood, drip irrigation or hand watering. If the hedgerow is next to cropland, overhead irrigation from the crop can be extended to water the hedge.

Keeping out weedy plants and destructive wildlife

One of the biggest challenges in establishing a hedgerow is keeping unwanted plants from taking over the new plantings. There are a variety of techniques to inhibit these weedy plants. The simplest method is to leave alleys between plant rows for mowing, cultivation or mulching until plants are well established. Ideally, an area 6 to 8 feet wide around the hedgerow should be mowed, flailed or tilled for weed management, fire protection and rodent control. It is also important to mulch heavily with a minimum of 3 inches of leaves, straw, sawdust or cardboard around each plant. As plants mature, they will eventually shade out most annual weeds. This is the ideal time to infill with low-growing, shade-tolerant plants.

If needed, protect plants from beaver and nutria with hardware cloth, and use partially buried plastic-coated cardboard or tubing around tree trunks to protect from voles and mice. If applying pesticides, follow the label in order to protect riparian zones along rivers, creeks and ponds from contamination.

Managing a hedgerow in the first few years is similar to managing a crop. Good weed management during establishment results in less labor to control weeds in seasons to come.

Cost of establishment

Planting hedgerows does not have to be expensive. Seedling plants are available at low cost, and you can propagate new plants from existing plantings. The larger the plant, the sooner it will reach maturity, which is especially important in creating a fast-growing privacy screen. This can be achieved by purchasing dormant bareroot plants and 1-gallon potted plants or larger. Remember, these larger plants will most likely require summer irrigation. Government programs are available to assist landowners with hedgerow development. Many counties have tax exemption programs for riparian lands, along with wildlife habitat conservation and management programs. See “Incentive programs to help with hedgerow establishment” and Estimated Costs To Establish Pollinator Hedgerows, in “Resources,” pages 9–10.

Conclusion

A hedgerow is a long-term commitment. With proper planning and care, it will take approximately four to eight years to establish a hedgerow and 30 or more years for it to reach maturity. To encourage success, draft a plan with planting installments for each year, depending on your goals and budget.

Hedgerows in rural agricultural or urban settings provide many benefits that increase over time, including the opportunity for supplemental income. With benefits for wildlife, humans and the planet, hedgerows are a practice that has stood the test of time.

Hedgerow plants

Hedgerows can contain native and non-native plants, although plants should not be invasive. The following trees, shrubs, groundcovers and perennial plants are appropriate for hedgerows in the Pacific Northwest. Remember to consider proper site selection and plant requirements. Plants that tolerate wet soil are indicated by an asterisk (*).

Sun-tolerant plants under 25 feet

- Arbutus unedo Strawberry tree

- Aronia Chokeberry Schubert

- Baccharis pilularis consanguinea Coyote brush

- Ceanothus velutinus Tobacco brush

- Cornus stolonifera Red twig dogwood

- Diospyros kaki Japanese persimmon

- Diospyros virginiana American persimmon

- Elaeagnus multiflora Goumi

- Elaeagnus umbellata Autumn olive

- Ficus carica Fig

- Fuchsia magellanica Hardy fuschia

- Lonicera caerulea Blue honeyberry

- Lonicera involucrata Twinberry

- Malus fusca West Coast crabapple

- Malus sp. Apple

- Morus Mulberry

- Myrica pensylvanica Bayberry

- Oemleria cerasiformis Osoberry

- Philadelphus lewisii Mock orange

- Prunus avium Cherry

- Prunus domestica Plum

- Pyrus pyrifolia Asian pear

- Ribes sanguineum Red-flowering currant

- Ribes divaricatum Black gooseberry*

- Ribes nigrum Black currant*

- Rosa nutkana Nootka rose

- Salix fluviatilis Columbia River willow*

- Salix hookeriana Hooker’s willow*

- Sambucus cerulea Blue elderberry*

- Spiraea douglasii Western spiraea*

- Vaccinium corymbosum Blueberry*

- Vaccinium ovatum Evergreen huckleberry

- Viburnum opulus Highbush cranberry

Sun-tolerant plants 25+ feet tall

- Abies grandis Grand fir

- Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf maple

- Alnus rubra Red alder*

- Arbutus menziesii Madrone

- Asimina Pawpaw

- Calocedrus decurrens Incense-cedar

- Castanea Chestnut

- Chrysolepis chrysophylla Golden chinkapin

- Diospyros virginiana Persimmon

- Fraxinus latifolia Oregon ash*

- Juglans regia English walnut

- Picea species Spruce

- Pinus ponderosa Ponderosa pine

- Populus trichocarpa Black cottonwood

- Prunus subcordata Klamath plum*

- Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas-fir

- Quercus garryana Oregon white oak

- Robinia pseudoacacia Black locust

- Thuja plicata Western redcedar

Groundcovers

- Fragaria chiloensis Strawberry

- Gaultheria shallon Salal

- Mahonia nervosa Oregon grape

- Polystichum munitum Sword fern

- Vaccinium vitis idaea Lingonberry

Vines

- Lonicera Honeysuckle

- Akebia Five-fingered akebia*

Plants for pond edges

- Typha latifolia Cattail*

- Ledum glandulosum Labrador tea

Plants that tolerate shade

- Chrysolepis chrysophylla Golden chinkapin

- Cornus nuttallii Western flowering dogwood*

- Corylus cornuta Hazel*

- Physocarpus capitatus Ninebark

- Polystichum munitum Sword fern

- Sambucus racemosa Red elderberry*

- Prunus virginiana Chokecherry

Plants for partial shade to shade

- Acer circinatum Vine maple *

- Amelanchier alnifolia Serviceberry

- Berberis aquifolium Oregon grape

- Gaultheria shallon Salal

- Cornus stolonifera Red-osier dogwood

- Holodiscus discolor Oceanspray

- Lonicera involucrata Twinberry

- Oemleria cerasiformis Indian plum

- Philadelphus lewisii Mock orange

- Rhamnus purshiana Cascara sagrada

- Taxus brevifolia Western yew*

- Vaccinium ovatum Evergreen huckleberry

Edge plantings

- Achillea millefolium Yarrow

- Arctostaphylos uva-ursi Kinnikinnick

- Berberis nervosa Cascade Oregon grape

- Calendula officinalis Calendula

- Cichorium intybus Chicory

- Foeniculum vulgare Fennel

- Fragaria chiloensis Wild strawberry

- Gaultheria shallon Salal

- Lavandula angustifolia English lavender

- Medicago sativa Alfalfa

Nuts

- Carya illinoinensis Northern pecans

- Carya ovata Shagbark hickory

- Castanea Chestnuts

- Ginkgo biloba Gingko

- Juglans ailantifolia Heartnut

- Juglans regia English Walnut

- Xanthoceras sorbifolium Yellowhorn

Plants for arid environments

Plantings around vineyards

Some flowering plants attract specific kinds of beneficials, for example, carnivorous flies (Oregon sunshine), predatory bugs (stinging nettle) and Anagrus wasps (sagebrush). Research shows trends of reduced pest abundance and increased beneficial insect diversity and abundance in vineyards with a diversity of native flowering plants compared to vineyards lacking native plants.

- Artemisia spp. Sagebrush

- Chrysothamnus, Ericameria Rabbitbrush

- Eriogonum compositum Northern buckwheat

- Eriogonum niveum Snow buckwheat

- Eriogonum elatum Tall buckwheat

- Clematis ligusticifolia Western clematis

- Eriophyllum lanatum Oregon sunshine

- Crepis atribarba Slender hawksbeard

- Asclepias speciosa Showy milkweed

- Achillea millefolium Yarrow

Arid trees

- Juniperus occidentalis Western juniper

- Larix occidentalis Western larch

- Picea pungens Blue spruce

- Pinus flexilis Limber pine

- Pinus edulis Pinyon pine

- Pinus ponderosa Ponderosa pine

- Pinus nigra Austrian pine

- Populus trichocarpa Black cottonwood

Shrubs

- Artemisia tridentata Big sagebrush

- Atriplex canescens Four-wing saltbush

- Cercocarpus montanus Mountain mahogany

- Chamaebatiaria Desert sweet millefolium

- Ericameria nauseosa Rubber rabbitbrush

- Cornus stolonifera Red-osier dogwood

- Mahonia repens Creeping Oregon grape

- Potentilla fruticosa Shrubby cinquefoil

- Prunus emarginata Bitter cherry

- Prunus virginiana Chokecherry ‘Schubert’

- Purshia tridentata Antelope bitterbush

- Rosa woodsii Woods’ rose

- Shepherdia argentea Silver buffaloberry

- Shepherdia canadensis Russet buffaloberry

Herbaceous perennials

- Antennaria species Cat’s ears

- Anaphalis margaritacea Pearly everlasting

- Aster alpinus Dwarf alpine aster

- Aurinia saxatilis Basket of gold

- Delosperma species Ice plant

- Echinacea purpurea Purple coneflower

- Ericameria nauseosa Rubber rabbitbrush

- Erigeron annuus Fleabane daisy

- Eriogonum umbellatum Sulfur buckwheat

- Eriophyllum lanatum Oregon sunshine

- Kniphofia uvaria Torch lily

- Lavandula angustifolia English lavender

- Linum lewisii Flax

- Penstemon pinifolius Pineleaf penstemon

- Rudbeckia species Black-eyed Susan

- Salvia dorii Purple sage

- Sedum spurium and album Stonecrops

- Sphaeralcea munroana Globemallow

- Rosa woodsii Woods’ rose

- Yucca glauca Narrow leaf yucca

Groundcovers

- Juniperus Savin juniper

- Arctostaphylos uva-ursi Kinnikinnick

- Sedum Stonecrop

- Sempervivum Hens and chicks

- Thymus pseudolanuginosus Wooly thyme

Incentive programs to help with hedgerow establishment

Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program

In exchange for removing environmentally sensitive land from production and establishing permanent resource-conserving plant species, farmers and ranchers are paid an annual rental rate along with other federal and state incentives. This program is administered through the USDA Farm Service Agency and local Soil and Water Conservation districts.

Environmental Quality Incentives Program

This program provides financial and technical assistance to agricultural producers in order to address natural resource concerns and deliver environmental benefits such as improved water and air quality, conserved ground and surface water, reduced soil erosion and sedimentation or improved or created wildlife habitat. The program is administered through the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service via local field offices.

Resources

Agencies

- USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service EQUIP Program

- USDA Farm Service Agency CREP Program

- Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

Books and publications

- Earnshaw, S. Community Alliance with Family Farmers. Hedgerows and Farmscaping for California Agriculture: A Resource Guide For Farmers.

- Guard, J.B. Wetland Plants of Oregon and Washington. 2010. Lone Pine Publishing.

- Imhoff, D. and R. Carra. Farming With The Wild: Enhancing Biodiversity on Farms and Ranches. 2011. Sierra Club Books.

- Kruckenberg, A. Gardening With Natives of the Pacific Northwest. 1982. University of Washington Press.

- Lee-Mäder, E., J. Hopwood, M. Vaughan, S. Hoffman Black and L. Morandin. Farming with Native Beneficial Insects: Ecological Pest Control Solutions. 2014. Storey Publishing.

- Link, R. Landscaping for Wildlife in the Pacific Northwest. 1999. University of Washington Press,

- Mader, E., M. Shepherd, M. Vaughan, S. Black, G. LeBuhn, Attracting Native Pollinators. 2011. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

- Martin, A., H.S. Zim, A.L. Nelson. American Wildlife and Plants: A Guide To Wildlife Food Habits. 1951. Dover Publications.

- National Center for Appropriate Technology, Oregon Tilth and The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Conservation Buffers in Organic System: Western States Implementation Guide. March 2014.

- Pojar, J. and A. MacKinnon. Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast. 2016. Lone Pine Publishing.

- Rodriguez, O. and R. Dufour. A Pictorial Guide to Hedgerow Plants for Beneficial Insects, ATTRA — Sustainable Agriculture Program.

- Rose, R., C.E.C. Chachulski, D.L. Haase. Propagation of Pacific Northwest Native Plants. 1998. Oregon State University Press.

- The Xerces Society. Estimated Costs To Establish Pollinator Hedgerows.

Pollinator guides and publications

- Beyond Pesticides, Bee Protective Habitat Guide

- Beyond Pesticides, Pollinator-Friendly Seeds and Nursery Directory

- Melathopoulos, A., N. Bell, S. Danler, A.J. Detweiler, I. Kormann, G. Langellotto, N. Sanchez, D. Smitley and H. Stoven. Enhancing Urban and Surburban Landscapes to Protect Pollinators, OSU Extension, EM 9289

- Pavek, et al. Plants for Pollinators in the Inland Northwest. 2013. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Technical Note No. 24

- Pendergrass, K., M. Vaughan and J. Williams. Plants for Pollinators in Oregon. 2007. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation,

- Pollinator Partnership

- Shepherd, M. California Plants for Native Bees. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

- The Xerces Society, Hedgerow Planting (422) for Pollinators: Western Oregon & Washington Specifications and Implementation Requirements

- The Xerces Society, Bee-friendly plant lists

- The Xerces Society, Habitat installation guides

- The Xerces Society, Pollinator Conservation Resource Center