Transcript

Speaker 1: From the Oregon State University Extension Service, this is Pollination, a podcast that tells the stories of researchers, land managers, and concerned citizens making bold strides to improve the health of pollinators.

I'm your host, Dr. Adoni Melopoulos, assistant professor in pollinator health in the Department of Horticulture. School's well on session, so it's time to check in with our sleuthing journal reading research retinue here at Pollination. These are undergraduates from Oregon State University, and this week consists of Lacey Jane, Addison DeBoer, Isabella Messer, and Umea Wright. This week they take up a paper that got a fair amount of press towards the end of the summer.

It's by Eric Mada and his colleagues at the University of Hawaii. Its title, Glyphosate, perturbs the gut microbiota of honeybees, and it was published in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. As many of you know, glyphosate is one of the most widely used herbicides. It's used in conjunction with a number of herbicide-tolerant crop varieties. Like a lot of herbicides, it's shown to be relatively non-toxic when applied to bees. In this study, they look at the indirect effect of the herbicide on the bees. Take it away, research retinue. In this episode, we're talking about this new paper that came out on glyphosate's effect on honeybee bee gut microbes. May I just start? What are these things that live inside bees' guts?

Speaker 2: In the same way that humans have our microbiome and we have lots of little critters living inside of us doing everything that needs to be done, bees have a similar... Well, they have the same thing, not with the same bacteria, but they also have a microbiome.

Speaker 1: What about herbicides? Herbicides kill plants. Why would anybody be curious about their effect on bees? Why is the study even done?

Speaker 2: This study was looking at whether glyphosate, which is a very common ingredient in many herbicides, could have any sort of negative effect on the bees' microbiota, and if in the same way, it kills parts of plants, if it would harm the bacteria inside the bees, and if that in turn makes them more susceptible to certain pathogens.

Speaker 3: So the way glyphosate works is it targets a particular pathway that's found in plants and microorganisms, and so because of that roundup, which is usually what glyphosate is in, is generally considered safe for animals, but the authors thought that because bees rely on this bacteria so much that's in their gut if that's affected, maybe it would have a less drastic effect on bees that would be harder to observe, and so they did this study about it.

Speaker 4: Yeah, something very related to what Addison just said, so the paper said from this quote, that animals lack the schichamate pathway, which is why glyphosate is considered one of the least toxic pesticides and used in agriculture.

Speaker 2: So it wasn't that the bees themselves have the pathway, but it is the microorganisms living inside of them and the bacteria that have the pathway, and so if it's harmful to the bacteria which helps the bee, then it will be harmful to the bee.

Speaker 4: So they investigated the effects of glyphosate exposure on the size and composition of the honey bee gut microbiome. Compositional shifts typically favored species tolerant to glyphosate and disfavor sensitive species.

Speaker 3: So they picked out seven different types of bacteria and then they looked at the absolute and relative abundances in the control right after they were noculated and then three days later. There's only a couple kinds of bacteria that are really statistically significant in this experiment. So there are two classes of bacteria. There's class one that is sensitive to glyphosate, and then there's class two that is supposed to be not sensitive to glyphosate, and those lactobacillus bacteria are supposed to not be sensitive to glyphosate. So it's weird that the single dose would affect them, but then when there's a double dose, there seems to be no change. I'm not sure what would account for that.

Speaker 1: Yeah, and it seems like in all of them the small dose is where you see the effect, at least in this first study. There are a couple of the couple bacteria, but nothing changes. They're just humming along. It's like, life's safe, no problem. Oh, listeners, if you turn your attention to this paper, you'll see that like there's a lot of variation.

Like they've got 15 bees lined up. We're looking at figure one. Yeah, figure one. Read along. And it's pretty amazing. Some bees got a lot of stuff, and some bees didn't get anything, whether they had glyphosate or not.

Speaker 2: Yeah, so the second part of the experiment is they exposed the honey bees to glyphosate, and then they also introduced a pathogen sriracha. It's kind of like the sauce, like the rooster sauce.

I mean, I don't know. So anyway, they introduced glyphosate and that pathogen to different sets of bees and saw how they responded to different combinations of the treatments. So if they had a healthy microbiome, then they would see what that... And then they measured the bee survival rate.

Speaker 3: I also wanted to bring up in this experiment, one of the things that they did was they used young bees that hadn't had any sort of microbiome built up. And so they were able to sort them into two groups. One of the groups was exposed to this gut homogeneous that they took from older bees. And so then they had about double what a normal bee microbiome would have had as far as bacteria, like amounts of bacteria.

And the second group had none of that. And so when it was exposed to glyphosate and the pathogen, the sriracha one, the bees that had none of the gut homogenate and the bees that had the gut homogenate and glyphosate were affected almost the same, which shows that the effect of glyphosate basically counteracts all of the positive effects of the gut homogenate.

Speaker 1: But the thing that they notice is that if they get glyphosate if they're fed glyphosate and they don't get the pathogen, they live fine. So in that top, you give bee glyphosate and no pathogen, they live, they seem to be doing okay, even though they've got these imbalances in their guts.

Speaker 3: So it's not that killing some of these salve bacteria will lead to increased mortality unless there's a specific pathogen, that it seems like the bees need this salve bacteria to fight against the pathogen. So then when they don't have that, because of the glyphosate, their mortality is almost 100%.

Speaker 2: So just to clarify, what you're saying is a healthy bee microbiome in combination with glyphosate, if it's exposed to glyphosate, basically is the same thing as a completely undeveloped bee microbiome.

Speaker 3: When it's exposed to this pathogen. Okay, got it.

Speaker 2: So I just brought up some of the assumptions that I saw in this paper, and there are two main ones that sort of stood out to me. The first one is the way that they sort of artificially composed of bees gut microbiome. And I don't know, it seems, I mean, I don't know how realistic the levels of bacteria that they gave to the baby bees, if that's actually reflected in wild bee populations, or if it's like super juiced up, and then if it's super juiced up, then like perhaps what they represent as a healthy gut microbiome is less important in wild populations, they sort of make it seem in this lab experiment. And then the second assumption that they included that sort of jumped out at me is the amount of glyphosate that they were exposing the bees to. It says that they gave them five and 10.

I want to throw the units at me. Okay, yeah, they gave them five milligrams per liter and 10 milligrams per liter. And the author said that that was representative of what it could be exposed to in the wild.

Speaker 1: There is this thing at the beginning of the paper.

Speaker 3: It says that it says that they test using concentrations of glyphosate that are documented in the environment. The amount that they use in the first experiment, says that an environmentally realistic concentration is between 1.4 and 7.6 milligrams per liter. When I looked at the paper that they referenced for that number, I found that the paper referenced a research journal.

Speaker 1: Which is in your hands right now?

Speaker 3: Yeah, so shout out to the Oregon State Valley Library. I got a copy of it, and it talks a ton about Roundup toxicity, but it's in terms of soil and aquatic invertebrates and not bees. And it doesn't talk specifically about how much bees would be exposed to.

Speaker 1: So we came across Marcelo next door, a weed scientist. He brought up this paper that was published in 2014 by Helen Thompson and her colleagues called Evaluating Exposure and Potential Effects on Honey Bee Breed Development Using Glyphosate as an example. Comprehensive study where they take they go in a greenhouse so the bees can't feed on anything else. You can imagine in a natural system, the bees can go to a lot of different places to get their food. But in this situation, they're trapped in a greenhouse with a real bee-attractive plant, a fecilia, it's called scorpion weed.

The bees are foraging on this and then they- Straight while they're foraging. Right. That was the other thing. They waited until it was 100 percent in bloom.

The only thing they could feed on and there was lots of it, and then they sprayed the glyphosate at the highest rate that the label would permit. During the day. During the day. So they didn't wait till nighttime.

They did full-time. So it was the worst case and they did that and they would measure the nectar that was stored in the comb and also the nectar that the bees were bringing back. In fact, the foragers on the first day had levels that were higher than were tested in the paper we're talking about with the microbiota coming back to the hive. But it went down really quickly. So it wasn't a real lasting effect.

And then the second thing is that they went into the comb seven days later and they looked at how much glyphosate accumulated in the comb and it was at the lowest dose in the study that we're talking about. So it was really useful. Yeah.

Well, I guess the other thing is we were talking about this. It's like, when is glyphosate applied typically to plants? Like we were talking to weed scientists and you apply to herbicide-tolerant plants, you typically apply the stuff very early.

So you do a spray before the plants come up and then at the four, you know, four-leaf stage, a very small plant, you spray it again, but you don't spray it typically in agricultural uses on full blooming plants. So in this, it seems like they get in that range in the study by really the worst-case scenario and a snapshot of time. So it may not be, it may be not the concentration that bees are really encountering in the environment.

Speaker 3: And with the young bees also, the forging bees are getting their pollen and nectar from a variety of plants, some of which have not been sprayed with herbicides. So it's likely that the concentrations of glyphosate coming back to the hive would be diluted by that too, which would also mean maybe it's not a normal concentration that they're getting.

Speaker 1: So it's a pretty cool paper, though. The techniques seem really amazing. And I was amazed to see all of these different bacteria and the bees got. What was the thing that you found most interesting about the study?

Speaker 5: I thought it was most interesting that they actually took up, took the bees and kind of ground them up into a soup and inoculated them that way, instead of allowing them to be inoculated naturally in the hive, as we've seen in the different part of the study. So I thought that was really interesting because I feel like that would achieve a much better baseline survey. So you're allowing all the individuals that you're testing to be inoculated with the same exact ratios of the gut biota that you are exposing them to.

Speaker 3: And then even with all of that to see how affected they were by the pathogen, when glyphosate was added, I think makes that part of the experiment really like a really strong argument.

Speaker 4: Oh, I had a question about the paper. So when they talked about the bees specifically, they always said honey bees. Do their information and data apply to native bees as well? Did you guys catch anything?

Speaker 2: I had the same thought. I had the same thought. At the beginning of the paper, they actually bring up the fact that this is relevant because bees will forage around the flowering weeds in fields. And just like from my observations, it's like there are flowering weeds in the middle of the field.

But I think that most of them are around the border. Which is like which I mean, anecdotally, is probably close to the natural areas where the native bees would come and wander in. So it looks like they only did tests on honey bees, but I could imagine this being relevant to non-honey bees. But also, I mean, all like we just published a bit of a paper about this looking at like the size of the bee and how far they can range. And so with that in mind, then it's probably this probably applies the most to honey bees because they can range over fields more than the smaller native bees.

Speaker 1: The last thing I wanted to ask you guys is I pulled up some science headlines. I think one of the things that we love to do in this segment is sort of like how science is translated. So I'm going to read you off a couple of them and tell me which one you think more accurately reflects a study. OK. All right. So the first one is popside.com. Weed killer weakens bees by messing with their microbiomes. Thumbs up or misuse of science.

Speaker 3: I think I would give that a thumbs up.

Speaker 5: Yeah, I agree. I think that's a pretty good explanation in common terms,

Speaker 3: especially the use of like weakens bees, because that's more of what we see than just like, oh, quite to say killing all the bees. Right.

Speaker 5: It's not it's not the application itself of glyphosate that is killing the bees. It's the effects that it has on the other micro biotic things that are living in their gut.

Speaker 1: All right. Here's Duccevella, a German broadcaster. Study shows glyphosate may be killing honey bees. It's a stretch.

Speaker 5: I agree that I think that that is kind of overestimating and oversimplifying some of the finer details in the studies that we've been reviewing in this podcast.

Speaker 1: All right. Last one. USA Today, weed killer, honey bee deaths linked in glyphosate study.

Speaker 5: I'd give that one a thumbs up. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker 1: Well, I'd have to say honey bee deaths linked like.

Speaker 3: There's a link. There is a link. In the second study, but not the first study necessarily, because the first study, didn't really talk that much about the mortality of the bees.

Speaker 2: The way that I have interpreted the data is that, yes, the use of glyphosate and herbicides probably does negatively impact pollinator populations or bee populations, but that's just sort of taking the data at face value. And when you sort of consider some of the other assumptions that they may have made during the process of this experiment, you know, that becomes a little bit more cloudy. But, you know, I mean, it seems unlikely to me that herbicide usage is helpful for pollinator-like populations. Just anecdotally, that like seems probably not true.

Speaker 3: I also want to address another assumption that I think this paper has for me, the whole study with the pathogen that they introduce seems pretty compelling and really important. But I wonder what the effects would be if it were a different pathogen. Like, is it only this serratea that's negative that has this impact? Like if you had other pathogens, would it have a similar effect? And I think that's something that would be really important when thinking about the larger effects of this study.

Speaker 1: OK. So we're so for you guys, you're going two for three on the headlines this week.

Speaker 5: Yes, I would agree.

Speaker 3: Can I say something else? Not about headlines? Definitely. OK. I just wanted to say one of the things I thought was most interesting was just the whole premise of this article, because so often herbicides and other things are tested in isolation, like, oh, is this safe for animals? Is this safe for plants? And I love that this considers that the bacteria in the beega has such an effect on the bees themselves. And I think that's really important.

Speaker 1: I agree. And I think, you know, a pesticide goes in the environment and just like how it affects. But also, how does it get to the bees? Like, you know, one of the assumptions in this paper is like there's a kind of like direct. But like, it's a complicated thing to imagine. People are using herbicides in many ways, and some of them may be very different from this. But then again, the effects may not be like it's not enough to test something and say, oh, it kills bees, like putting them in a petri dish. For here, if you took the glyphosate and put it on a bee's body, you would see no effect.

Speaker 3: What if you looked at this over time and generations of glyphosate affecting as Alvi in bees and then that's passed on and then eventually would with the salvi use a different like a different pathway where they're resistant to glyphosate or would that totally disappear in bees?

And then if there's the path like. One of the things that they looked at was there's this specific bacteria in honey bees that is sensitive to glyphosate most of the time. And so that was affected. But then other strains of the same bacteria, it's called S. Alvi were not affected. And they hypothesize that this other strain doesn't use the same enzyme pathway that glyphosate targets.

And so I'm wondering if honey bees are exposed to glyphosate enough, would there be enough selective pressures that the honey bees would rely more on these strains of S. Alvi that aren't sensitive to glyphosate, and would their health suffer from that at all?

Speaker 5: Well, and I think it would be a good idea to do kind of like a long-term or at least generational studies. So you're coming back to the same hive over time and monitoring the variants and microbiota and the pathogen and what kind of those effects are on mortality over a longer time scale. I think that would give you a better link between glyphosate and honey bee death in quotes.

Speaker 1: Thanks so much for listening. Show notes with information discussed in each episode can be found on pollinationpodcast.oregonstate.edu. We'd also love to hear from you and there are several ways to connect. For one, you can visit our website to post an episode-specific comment, suggest a future guest or topic, or ask a question that could be featured in a future episode. You can also email us at [email protected] Finally, you can tweet questions or comments or join our Facebook or Instagram communities. Just look us up at OSU Pollinator Health. If you like the show, consider letting iTunes know by leaving us a review or rating.

It makes us more visible, which helps others discover pollination. See you next week.

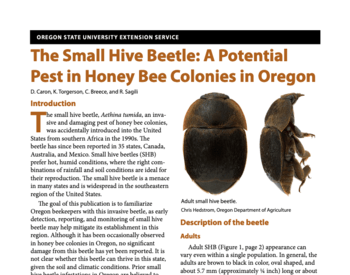

The OSU Research Retinue goes into depth on research papers that have been recently featured in the news. We convened Retinue this week to review a paper that got a fair amount of press over the past few months. Glyphosate is the most widely used herbicides in the world and is regarded as relatively non-toxic to bees and other pollinating insects. A study by Erick Motta and his colleagues from the University of Hawaii at Manoa demonstrate an indirect link between glyphosate and honey bee health in a laboratory study, namely a link to bacteria found in honey bee guts that helps fend off diseases.

This week’s retinue consists of OSU undergraduates Addison DeBoer (Biochemistry and Molecular Biology), Lacey Jane (Zoology), Isabella Messer (Horticulture) and Umayyah Wright (Geography).

Learn more about the recent research studying the effects of glyphosate on honeybees, and how glyphosate can indirectly affect their gut homogenate.

You can Subscribe and Listen to PolliNation on Apple Podcasts.

And be sure to leave us a Rating and Review!

“Those lactobacillus bacteria are supposed to not be sensitive to the glyphosate, so it’s weird that the single dose would affect them, but when there’s a double dose, there seems to be no change.” – Addison DeBoer

Show Notes:

- What makes up the microbiome of a honeybee

- How glyphosate works as an herbicide

- Why glyphosate indirectly affects bees health

- How the study was conducted

- The two different kinds of significant bacteria found in the honeybee gut

- What could have improved the study

- How the timing and frequency of applying glyphosate affects honeybees

- The different ways that science and news outlets are reporting this story

“The bees that had none of the gut homogenate and the bees that have the gut homogenate and glyphosate were affected almost exactly the same, which shows that the effect of glyphosate basically counteracts all of the positive effects of the gut homogenate.” – Addison DeBoer

Links Mentioned:

Check out the studies mentioned on today’s episode:

- Motta, V. S. E, Raymann, K, and Moran, N. A. (2018) Glyphosate perturbs the gut microbiota of honey bees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), (41): 10305-10310

- Thompson, H. M., Levine, S. L., Doering, J., Norman, S., Manson, P., Sutton, P., and von Mérey, G. (2014). Evaluating exposure and potential effects on honeybee brood (Apis mellifera) development using glyphosate as an example. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 10(3): 463-470.