Transcript

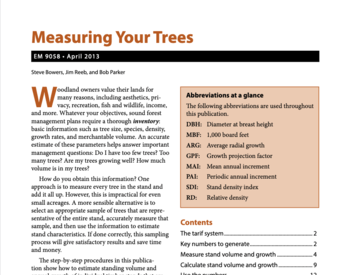

From the Oregon State University's extension service you are listening to In the Woods with the forestry and natural resources program. This podcast aims to show the voices of researchers, land managers, and members of the public interested in telling the story of how woodlands provide more than just trees, they provide interconnectedness that is essential to your daily life. Stick around to discover a new topic related to forests on each episode. Welcome back to another episode of in the woods, I'm your host Lauren Grand, assistant professor of practice and extension agent in Oregon State University's college of forestry. Today's topic is wildlife, our guest today is Thomas Stokley, Thomas is a forester and ecologist with OSU extension service and has a bachelor's degree in environmental science from the University of Missouri and a master's in phd in forest and wildlife ecology from the Oregon State University's college of forestry. As the forestry and natural resources extension agent serving central Oregon, Thomas's role is to provide science-based education to communities on the management and conservation of forests and the wildlife they support. He provides technical support to help inform land management decisions at local and regional levels with a focus on cross-boundary partnerships and attaining a balance between economical, ecological, and societal values. Welcome Thomas we're really glad to have you. So, today Thomas and I are going to be talking about wildlife, and just so that we're all on the same page, Thomas can you first define what wildlife is for us? So, many folks think about furry or feathered creatures when they talk about wildlife, but technically wildlife are any non-domesticated creature that exists out there in nature. Generally speaking though, we often designate the term wildlife to include animals, typically vertebrate animals, uh like mammals birds reptiles and amphibians, but really insects and other arthropods are wildlife too. Even bacteria and fungi can be considered wildlife as they're part of ecosystems. So, you know in forestry when we talk about wildlife we're typically thinking about mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians not necessarily insects, but technically speaking any non-domesticated creature. Wow that's a broader spectrum then I was expecting you to say. So, lots of things to think about when we're talking about wildlife, um but a lot of people wanna , they wanna know, how do wildlife live so can you give us a little bit of a background of what wildlife habitat is? So, yeah, that's kind of the hardest part for me whenever I think about wildlife habitat because really habitat is species specific and habitat's really the resources and conditions that exist in a given area that that an animal occupies or an organism occupies. So, we often talk about what is suitable habitat and suitable habitat means that that those given resources will allow that species or those individual organisms to survive and also reproduce, so that's really why it's species specific because habitat are those resources that a given organism uses to survive and reproduce. Not just an overarching term for a given area. But we also talk about habitat associations, so mixed conifer forest for instance you might think of a certain species like um the Orange Crown Warbler using these broadleaf habitats, so associations habitat association is typically what we talk about more broadly when we speak about wildlife habitat so what is a species associated with. So, you know a given butterfly might be associated with a meadow alpine meadow or um a woodpecker will be associated with dead wood in a forest, so broadly speaking wildlife habitat or all those resources that a given species needs to survive and reproduce and those resources we have this broad categorization of them to include food, water, cover in space and so the food and water you know obviously everything needs food and water to survive and reproduce but those cover resources are really important for a variety of species, so it could be a nesting cover for a song bird, it could be dinning cover for a small mammal, or a bear. It could be thermal cover for mule deer during the winter time where they need to stay warm under the closed canopy of a dense forest, or stay cool under the closed canopy during the summer. And then space is really critical and different species use space differently, so you might have a given beetle that will only occupy a few square meters of a forest versus something like a mule deer will occupy you know they'll travel very long distances requiring a variety of different habitat types during their life cycle. So, and and the cover really depends on the available resources for that given organism so if there's a whole lot of resources they might not need to travel as far to attain those resources versus if uh you know like say in a more limited environment like a dry forest mule deer will occupy a much larger area than say a blacktail deer on the west side which has more forage resources available so they don't have to travel as far to get those forage plants. So, that's a it's a really interesting concept you bring up, a lot of people talk about creating more wildlife habitat, but like you said, wildlife habitat for what? Um it's really species specific so um I think that's really important to think about and that we can always start thinking about as um we think about how forests are managed for different objectives. I hear this word niche come up a lot can you talk a little bit about what the difference between habitat and niche is? Yeah, so, you know habitat we typically think of the physical environment that a given organism lives in and a niche is really the range of conditions that a species will exist. With no two species being able to occupy the same niche at the same time in space. So, that basically it's very theoretical when we talk about a niche, and it also involves the relative role an organism has in the environment and you know, for instance, Pileated woodpecker are cavity net cavity excavators and so they perform the role of you know chiseling away at the bark and creating these cavities and then that ends up you know that's that's the role of that organism but also um we have to think about the realized niche, we call it a realized niche which is kind of funny to think about, but essentially the niche has to account for interactions with other species. So, if you have a species that's going to be competing with another species or you have a predator in a given area, that's really going to limit that whole niche breadth, the the range of conditions that a given organism can live in because if they're going into an area that seems like suitable habitat, but there's a predator there that precludes them from surviving, then it's not really suitable anymore. So that when we talk about niches we have to think about competition and predation and interactions with other species because uh no no single species or multiple species can't really occupy the same niche in the same time and space due to competition excluding one another. So I get I guess I get kind of confused when we talk about niche and habitat a lot I think a lot of people use them interchangeably and niche is a lot more theoretical sort of a range of conditions that a species might exist in, whereas habitat would be those specific locations that that organism is occupying. And you know really, for instance, like if the habitat is suitable and a given organism has to travel really far to find that suitable habitat and then once they get there there's a competitor or there's a predator, it's not necessarily a suitable habitat for them so a it's kind of is a lot more theoretical and habitat's a little bit more tangible, and then the niche also sort of accounts for the role that that organism plays in the environment. Thanks for clearing that up you know it's um, sorry were you gonna say something else? I think that's it. Okay, all right, so now we've covered sort of what wildlife is and what habitat is, so since this is a podcast about forests can you talk to us a little bit more about if maybe there's a sweet spot for when forests provide the best habitat for wildlife? Yeah, that's another it depends kind of answers I would say not really because it's species specific. So, if you think about a given forest that burns down for instance in a wildfire or is harvested during you know a clear cutting operation over on the west side, there's a whole sort of successional trajectory that that forest takes on going through this early successional stage where you get a lot of forbs and shrubs filling in after that big disturbance, followed by the trees filling in. And to where they start to close canopy and limit the understory development, and then over time as those trees mature the forest starts to open up again where you have some trees that are just old and decadent, dying creating canopy gaps and opening light resources and nutrients in the understory allowing that flush of understory vegetation again. So, when it comes to wildlife species it really depends on what their suitable habitat is and what their associations are during the early successional stage that flush of resources and the understory all the forage being produced all the nesting habitat really attracts a variety of different wildlife species from deer and elk to migratory songbirds that occupy those broad leaf habitats here in Oregon. And we can we often characterize that early successional stage as being really diverse when it comes to not only plant life but also wildlife and animal life, and as that forest closes it closes in the canopy closes there's it's a little bit more limited to species that require closed canopy conditions, so the understory starts to become dark there's less forage in the understory, but like for instance deer and elk that are a generalist species, meaning they can use a wide variety of different resources, they'll use those closed canopy conditions for thermal cover for hiding cover from predators. There are certain birds that will occupy those close canopy conditions like the northern goshawk will occupy sort of dense mature forests and then once you get to that older mature forest stage and the old growth stage you get a lot of species start to filling in start filling in again and some species will require that old growth they're associated primarily with old growth like the northern spotted owl or flying squirrel and typically we think of that early successional stage as being the most diverse when it comes to wildlife, but then also oil growth uh are also quite diverse because of that diversification and the and the forest structure so you got a lot of understory some mid-story and then those dominant tree species and a lot of different structures there for different species. So, it really depends on the organism you're talking about in terms of sweet spots but in terms of diversity you kind of get a high diversity early on and also later on with that middle stage being a little less diverse and and more suitable for uh less variety a lower variety of species. Great, so there's a lot of forest that we have in Oregon that are sort of in that mid range where maybe diversity isn't as high as the edges, what are some characteristics that a landowner or somebody who manages for us could include when um managing to be able to increase some of that diversity? Yeah, so, in in the forestry slash wildlife world the there's sort of these main characteristics we talk about when we talk about things that we can manipulate through silvicultural practices that will promote habitat resources for different species and broadly speaking those include the vertical structure, meaning the bottom of the forest all the way up to the top, so your understory your mid-story your over story species that's an example of vertical structure. So, there are these relationships where if you have more diverse vertical structures, so more canopy layering, you can fit in more bird species for instance, and so creating that vertical structural complexity can benefit a variety of different wildlife species because you have some understory associated species, mid-story, and overstory associated species. Then along those lines we also have horizontal structure which is you know think of it as a as a plane as you look across the forest and that would include you know how many trees per acre you have, are there openings?, you know, are there dense patches of forest?, and so similar to vertical structure increasing horizontal structural complexity can benefit a wide variety of species because you can have openings that would serve as foraging habitat for say deer and elk as well as these dense cover patches that different critters can use for hiding or nesting cover, and within that, we also want to include the vegetation composition so what species are there you know are there berry producing shrubs for instance in the understory do you have you know mature uh like hemlock and an old growth?

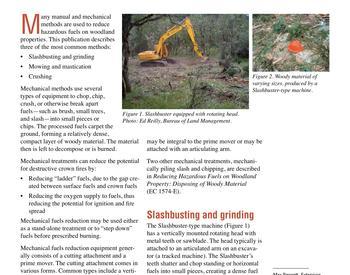

And so we really have to think about what types of plant species are there because different wildlife species will use different plants differently. And then we don't have to just think about the live vegetation but also the dead ones and standing dead wood otherwise known as snags and also fallen dead wood otherwise known as just down logs, are really important for a variety of of different species and and a lot of species will use that coursewood habitat throughout their life cycle. So, for a snag that might be really important foraging habitat for a woodpecker or a nesting habitat for a bluebird and then the fallen dead wood can be really critical for species that need to stay moist during the summertime like amphibians you know will sort of burrow into those course into that course wood. Black bears will den underneath large dead down logs and so we we really need to think also about the the dead tree components as much as we think about the live tree components when managing forests for wildlife. Yeah those I hear that from all of my wildlife biologist friends that we need more dead wood everywhere. That's a kind of it depends you know because it's not just you know the amount of dead wood but what the deadwood is you know coarse deadwood certainly is missing in a lot of areas where we have historical logging practices that had limited the amount of large diameter trees that would have ended up dying and becoming those coursewood habitats. And and you know also there's this whole idea of fire risk as well we don't want to just have tons of accumulation of dead wood and the understory specifically here on the eastside forest because in the east side we'd have had more frequent fire that would have limited the accumulation of that dead wood, specifically the fine dead wood, you know if you think about building a fire when you're out camping you don't just try to put a flame to a big round you know big log and expect it to burn you need a lot of fine wood as well. And so that can also pose a risk because we don't necessarily want to have these forests that are just chock full of fuels so there's a balance that really needs to be attained there when it comes to reducing fuels while maintaining that deadwood component and maintaining that diversity uh vertical and horizontal structural diversity in the forest for promoting wildlife. And there are many ways we can do that and focusing on those main elements while reducing fuel loading is important here on the east side, on the west side those forests are a lot more characterized by just dense vegetation. So, it really depends on where you're at in the landscape when we're talking about these different resources. Okay that's great so making sure that we have the right deadwood. Um, okay, so a lot of the properties that we I've sort of mentioned here in Oregon are managed on a parcel by personal basis or ownership by ownership and how does that affect wildlife and their habitat characteristics as they move around throughout their range? Yeah, this can be a really big issue in certain areas and it relates to that space component that I talked about earlier when it comes to those habitat resources and animals needing space. So, connectivity is one big one, and whenever it comes to highly fragmented landscapes where there's a variety of different ownerships, that can limit for instance the dispersal of say a flying squirrel that you know they're young should you know whenever whenever they're born, the young will then um disperse on to different areas, but if they're cut off from that mature forest that's you know 30, 40 miles away, and there is an area where they don't have tree cover, where they don't have those structures to fly and travel from tree to tree, when I say fly, glide from tree to tree, you can really limit the movement and dispersal of those organisms. And that has implications for not only the population, but genetic diversity which we're finding more and more is really important to sustaining wildlife populations into the future. And so really it's important for folks to be working together when it comes to land ownership managing in a way that they can help to increase that connectivity, so um, but also you know it also presents opportunities as well because if you know a given landowner notices that there's certain resources missing in the landscape like that coarse dead wood component you know they might be able to provide that on their property and provide that as a source habitat for species depending on the acreage of that land. But fragmentation is a big one, and for certain species though like say um deer and elk that that are generalist species, those edgy areas those what we call edge habitats, um those can be really important for them because they have you know they have their openings where an area was harvested they have you know their closed canopy conditions and and folks parcels that you know don't necessarily harvest their trees like that you know through regenerative harvesting, so it can present opportunities for generalist species, but it can really limit specialist species that require especially old growth conditions. Or you know in the case of an area where there's no openings that can limit the forage production and limit that broadleaf component of the forest it's really important for a variety of songbird species. Okay, let's talk about management, so we talked a little bit about what forest characteristics can influence wildlife populations, what are some ways that we can enhance these characteristics during certain management activities, so let's say someone is doing a clear-cut harvest what are some things they can do to try to benefit as many wildlife species as possible? I'm going to first add to that previous point and talking about the space aspect of things, it's really important to know what's in the landscape uh what's what's already there what might be missing and also think about the species that you're wanting to manage for if a given plot of land is too small even though you have say like some old growth trees on your property, if that parcel of land is too small, it's it might not be suitable for a species like like flying squirrel if it's it's too small. So, you know going on to the next question, uh really important to you know know what the past the historical conditions were of the forest?, What's available in the landscape?, What might be missing?, And how much connectivity there is? So during like say clear cutting operations, if you're wanting to promote um diversity of a diversity of wildlife species retaining live trees can be important um especially retaining snags, so those that dead standing wood, and keeping slash creating coursewood can really present an opportunity for different species. And then if there is you know if the management objective is to remove the the logs for economic purposes landowners can also create these uh habitat wood piles or some folks called bio dens where they use sort of the finer smaller diameter logs and you stack them sort of like lincoln logs cross hatch stack them and then cover those with fine fine materials and as a roof and that can provide space for different critters to to den or nest within those wood piles. So, if you're wanting to do a clear-cut harvest operation it can be pretty critical not to just burn every single slash pile you have but intentionally create them in a way that can provide cover for different species, and disperse the coursewood component in a way that allows facilitates movement of animals throughout that harvested area. So, you know you don't want to just have a com very large opening with one wood pile in the middle of it because you know a given rodent or bird might not necessarily be able to get there in the case that a predator is seeking them out so having you know dispersal of those resources throughout a harvest unit can be pretty critical for the movement of creatures. And um you know when we talk about reforestation oftentimes vegetation management is a primary objective is to reduce the amount of competition so that you can get your trees to grow as fast as possible, but we've done some recent research actually that's actually being published it's in production right now about ecosystem services and biodiversity in these managed forests that essentially allowing some of that vegetation to retaining some of that vegetation whether it's a skip in your herbicide treatment, or intentionally planting forage species in certain areas, but retaining patches of native vegetation can be quite critical, so you don't necessarily just want a homogeneous stand of Douglas fir, allowing some of those broadleaf species to regenerate it's really important, and some work from Tana Ellis and Matthew Betts found that you don't even need a whole lot of it to promote songbirds uh diversity of songbirds really only ten percent of these areas if you have ten percent broadleaf cover that can be quite beneficial there's sort of a threshold at over 10 percent um or up to 10 percent you have great increases in songbird abundance and diversity. So, you know that's more for for regeneration harvest like clear cuts and we're talking about thinning you know we don't we also if we want to promote wildlife species whether it's thinning for commercial purposes, thinning to reduce fuels, you can think about variable density thinning or variable retention harvests where you thin at different densities so that you have some dense patches, you have some that are fairly evenly thinned out, and then openings as well, and those openings can promote that forage for say deer and elk, or the broadleaf component for neotropical songbirds, and during those sending operations you know it's a good up it's a really good time to start thinking about creating snags dropping trees to promote that down course wood.

And really you know trying to maintain uh what we call these biological legacies these old trees that have been there for a while keeping them around can be quite critical in both clear cutting and thinning operations. And you know it's really important because some species are associated with that coursework component, but some of those trees that are really old biological legacies aren't really it's not really financial financially feasible to remove them and and so um yeah those you can think of those like real gnarly wolfy looking trees and keeping them and those harvest units can be quite beneficial for different species, but at the minimum, really you know following the forest practices act rules for retaining you know live trees and snags, and also riparian zone management, where you um have your riparian buffers and you know at the bare minimum follow the Oregon force practices act, but if you retain more of that riparian vegetation a lot of wildlife use those riparian zones as travel corridors, so you know the more you have that vegetated the more you have extreme cooling you have cover for species that are seeking out water if if they're very exposed they might not go to that water because it might be a risk for predation. So, retaining you know different levels of vegetation along those riparian quarters can be pretty important for the species that use them, and not to mention uh inputs of dead wood into the stream can be quite critical in those riparian zones. Okay, well I think we've got some good information now about what wildlife are and their habitat and some ways to benefit their habitat during management practices. Can you offer some resources for people about how they can find out about what species might be in certain forests?, or if they own property, what species might be on their property? Yeah, you can contact your local Oregon department of fish and wildlife wildlife biologist. We've got wildlife biologists distributed all throughout the state, so that would be a good first place um to give them a ring ask them what they might find in their properties, um, not to put in a plug for OSU extension, but you can talk contact your extension forester I know Lauren you know quite a bit about wildlife so you'd be a good resources for the folks there in lane county, but there's a wide variety of information it's it's a little overwhelming at times but i would suggest you know um Oregon department of fish and wildlife would be a good first start. And then you can get just local guides to see you know what a species is typically associated with, so there's a variety of different bird guides, reptile, and amphibian guides, and you know just get some field books and take a walk out in the forest and start thinking about what resources you have on your property and what might be associated with those areas. Yeah, those are great resources. One of my favorite resources that I learned about recently was the biodiversity index that the Oregon department of forestry and Oregon woodland explorer have together to where you can just put in a location and it'll actually give you a list of some of the potential species that might be out there. It's not a guarantee, you have to do some of that you know um field book walking around, but um that's another resource that I find useful. Yeah, the Oregon explorer I think is a really good resource, and um ODFW is also coming up with a list of of different species that you might find around in the state, so they've got you know what the species is and what they're they're typically associated with, but yeah the Oregon explorer is a really great resource especially for those habitat associations. Okay, well thank you so much for joining us and talking about wildlife. Uh, before we come to a close, I have a few questions that I like to ask all of my guests, and uh the first ones are real um, Can I go back? Yeah. Um you know it's great to contact different professionals around the area to learn about what might occupy your forest, but I'm a really big fan of like game cameras, or what we call in the scientific community camera traps, so they're really awesome because you can set them out in your forest you know they're passive they they sense infrared or heat and motion. And so if you set them a little bit up high around breast height you might be able to capture some of your larger mammals like deer and elk, if you set them lower down to the ground you know around one to two feet off the ground you'll be able to pick up rodents and other smaller animals. Then looking for tracks you know go find a muddy area or an area down by a stream and you can look for animal tracks and and use a field guide to identify those tracks. Look for their scat or their poo you know if you if you want to really get that deep into it um, and also you know i'm not really a professional birder by any means but i certainly love to listen for them and learn about them so that's a really easy way to find out what's on your properties get a bird book and you know there's the Cornell bur ornithology institute which is really great for helping to identify different birds, and iNaturalist as well is a really great resource to find out what's in your area, because you can find other folks that have documented different species. But going out in the woods exploring and trying to find out what's there I think is the best way. And there's a lot of critters you're not going to see that's that's the beauty of it is you know might need some camera traps to set up if you're really curious. Well I'll take any excuse to get out in the woods more so, but thanks Thomas I'm really glad you were able to join us today and chat with me about one of my favorite topics in forest which is wildlife. Um I have a few questions to ask you that I ask every one of our guests and the first one's a real brain scratcher, what's your favorite treat? Yeah, that's a hard one, I would say hard wood because it's hard question, but lately I've been a real big fan of western larch. It's really fascinating to me it's a deciduous conifer so it loses its needles in the winter time, and it can be very large, and they're fire adapted. And currently you know due to the lack of fire they need a little bit more protection and management to promote them throughout their range, they're becoming more limited due to that competition with other conifers that are less fire adapted like like your true first species so a big fan of western large it's just and it's beautiful in the fall it turns yellow it's just yeah near and dear to my heart, I really like that one. Yeah, gorgeous tree, I haven't had the pleasure of living near them yet, but maybe one day. Um, okay, so our second question is what's the most interesting thing that you bring with you into the field whether it's in your cruiser's vest or field kit. Yeah, I guess any type of lens really. Whether it's like a hand lens to look at the very small things or binoculars, um cameras, camera traps. Anything with a lens I think is really important for me when I go out in the woods. You know, and again like the camera traps, like I can't be out there 24 hours a day looking for creatures so setting them up in a good location you can learn a lot about what's going on in your property. And then you know in terms of like getting down to the really fine things, the hand lens is really cool it's a whole different world once you look look deep into it and binoculars that's pretty obvious one for anyone that's into birding or hunting and how much you see whenever you're able to zoom in. Yeah, surprisingly, I just started using a pair bringing a pair of binoculars with me and I took way too long to get there I'm glad I carry them now. So, our last question um has to do with resources, I know you offered a lot of resources already, but is there anything else or anything in addition that you haven't mentioned yet that you would recommend to our listeners if they're interested in diving a little deeper into wildlife as they pertain to forests? Um, yeah, again you know it's I think it's great to go check out the Oregon explorer app online it's a really awesome resource to use to find out more information about the forests you uh the force you have in a given area what types of wildlife you might see

and you know we could put in a plug for tree school I know that you all end up bringing a lot of wildlife biologists into those programs to talk about um wildlife tree school is an excellent resource and a lot of those are recorded online. Um and yeah here in eastern Oregon we have this publication called life on the dry side and we typically will mention a little bit about wildlife there, but um yeah I would say you know check out the Oregon department of fish and wildlife webpage about different species learning more about what might exist in in your given forest you can check out the U.S. fish and wildlife service webpage they have a lot of good good information about different organisms that are typically going to be more the organisms that are protected.

And yeah, just get some books and get some field guides these are always great resources, and um yeah we've actually got a great resource that I'm now a part of I'm really happy to be on board with this is the woodland fish and wildlife group and if you just google woodland fish and wildlife publications we've got a whole set of publications about wildlife varying from we're working on one about small mammals now, they've got one on like pond turtles, um you can find information on wildlife friendly fuels reductions and that in those articles. So it's woodlandfishandwildlife.com and that's a pretty great resource there's a whole team of us a wide variety of different backgrounds whether it's working for the state, feds, private, it's really great so I think it's quite objective and we all are great at checking each other and making sure we're presenting objective information in those publications. Those are some really great resources, thank you so much for sharing them, and for all of your great knowledge today Thomas we're really glad you could have joined us to talk about one of my favorite topics in forestry, wildlife.

Thanks so much for listening, show notes with links mentioned on each episode are available on our website blogs.oregonstate.edu/inthewoodspodcast. We'd love to hear from you visit the tell us what you think tab on our website to leave us a comment, suggest a guest or topic, or ask a question that can be featured in a future episode. And also give us your feedback by filling out our survey. In The Woods is produced by Lauren Grand, Carrie Berger, Jacob Putney, Stephen Fitzgerald and Jason O'Brien who are all members of the Oregon State University forestry and natural resources extension team. This podcast is made possible by funding from the Oregon forest resources institute music for in the woods podcast was composed by Jeffrey Heino and graphic design was created by Christina Freehoff. We hope you enjoyed the episode and we can't wait to talk to you again next month. Until then, what's in your woods?

you

In this episode, Lauren Grand discusses the relationship between forests and wildlife with Thomas Stokely.