CORVALLIS, Ore. – Eastern Oregon wheat farmers face a daunting situation – persistent weeds becoming resistant to the commonly used herbicide called glyphosate.

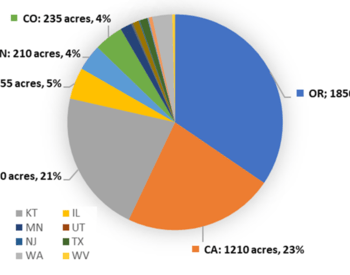

In the Pacific Northwest, Russian thistle infests nearly 5 million acres and costs farmers more than $50 million annually in control measures, according to Judit Barroso, an Oregon State University Extension Service weed scientist and associate professor in the College of Agricultural Sciences. Where severe infestations occur, Russian thistle reduces wheat yield up to 50%, diminishes harvest efficiency and can prevent wheat harvest entirely.

Farmers have used glyphosate, sold commonly as Roundup, for decades to effectively control weeds, including Russian thistle (Salsola tragus), the most frequent tumbleweed in the Pacific Northwest. There’s evidence that downy brome (Bromus tectorum) is also becoming resistant.

“Glyphosate is very convenient for growers because it’s very cheap and controls many species,” Barroso said. “But there need to be alternatives.”

In 2017, Barroso began researching possible alternatives to glyphosate to help growers avoid the increasing problem of resistance and successfully thwart Russian thistle and other weeds. She studied the effects of residual herbicides that provide extended control in no-till fallow fields in collaboration with Larry Lutcher, OSU Extension faculty in Morrow County, and Drew Lyon, a scientist from Washington State University. In 2021, she started another trial on no-till and tilled fields to find alternatives to glyphosate, a non-selective herbicide that kills anything it touches unless it has developed resistance.

The most effective Russian thistle control with residual herbicides was obtained with Spartan Charge (sulfentrazone and carfentrazone) and Fierce (flumioxazin and pyroxasulfone) applied in spring, although in some years and locations, a similar control was found by applying those herbicides in the fall as well. With alternative post-emergence herbicides, Barroso found that the tank mixes between glyphosate plus Reviton (tiafenacil), and Reviton plus Vida (pyraflufen) produced similar control in Russian thistle as glyphosate applied alone.

Russian thistle thrives in the dry climate of eastern Oregon and Washington and if left unchecked develops an extensive root system that competes with wheat for water and nutrients. When plants are large, they break off at the lower stem and roll through fields dispersing more than 40,000 seeds per plant.

Traditionally, growers in eastern Oregon relied on tillage to control weeds. And although tillage can control weeds successfully, it breaks up the soil structure, contributes to erosion and prevents water infiltration, Barroso said. No-till farming has been proven to do a better job infiltrating water in the soil, reducing soil erosion and maintaining soil structure. However, no-till farming relies only on herbicides to control weeds and is producing weeds becoming resistant to commonly used products like glyphosate.

Those conditions have caused many growers to consider returning to tilling, Barroso said. Long-term sustainability of dryland fallow-based wheat production systems depends on the development of weed management plans that are less reliant on repeated application of glyphosate.

“Using a range of herbicides is best,” Barroso said. “Growers should work to diversify their weed management strategies as much as possible. Although, indirectly we’re asking them to spend more money on weed control.”

Barroso and growers are looking forward to lower prices on alternative herbicides as demand grows.