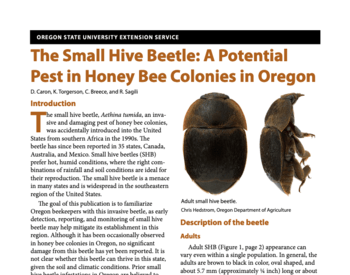

Transcript

Speaker 1

From the Oregon State University Extension Service, this is pollination, a podcast that tells the stories of researchers, land managers, and concerned citizens making bold strides to improve the health of pollinators. I'm your host. Doctor Adoni Melitopol, is an assistant professor in pollinator health in the Department of Horticulture. Florida seems very different from Oregon, but as you're going to hear in this episode, there are a lot of similarities when it comes to pollination. This week we're talking to Doctor Rachel Mallinger. She's an assistant professor at the Department of Entomology and Nematology at the University of Florida. She has an extension appointment. Very much like mine here in Oregon as well as a very vibrant research program. And as you'll hear in Florida, there are a lot of similar concerns. There's a lot of interest in blueberry pollination. There's a lot of interest in pollinators in forests and also the intense interest from the Master Gardeners in terms of pollination is something that's shared in Florida. So let's take a trip right across the continent and let's talk with Doctor Rachel Mallinger about pollinator issues and extension in Florida. OK, well, Doctor Mallinger, welcome to pollination. Now, Florida is a pretty exotic place, especially to us Oregonians are probably as far away from hurricanes as you can get them in the continental US. Can you tell us a little bit about the bees of Florida and some of the challenges?

Speaker 2

Thanks for having me.

Speaker 1

They face and what do we want to some of the specific needs for pollinator health in Florida?

Speaker 2

Yeah, that's a great question. So I moved here from North Dakota and it is about as different as you can get and you know certainly it's different from Oregon so in terms of the bees, in particular, Florida is pretty unique. So we don't have a cold that much of the rest of the country gets and a lot of these species. Require that cold so Florida has a lower B diversity than much of the rest of the. Country so there. There are about an estimated 315 species of native bees in Florida compared to 506 hundred close to 1000 in the. Southwest has a lower B diversity and in particular certain groups like bumblebees. We don't have as many species of bumblebees and they're not as common, but we also have certain bees that you don't find elsewhere, so there are a lot of parts of the bees. These are bees that are ground nesters, they're very small, and they like sandy soils, which of course we have a lot of here in Florida. So the the B community is a little bit different in terms of some of the challenges that they face. I think there are some aspects of Land Management as well as land use change that are unique to Florida. So of course, Florida is one of the most populated states in the country and is undergoing rapid development. It also has still a fair amount of cropland. So just in terms of habitat loss and development, I think that. That worse than many other places is just a really big pressure on bees and on other wildlife too and other sort of Land Management aspects that may be unique to Florida, some of much of Florida is actually mid-forested, especially in the northern half or so and. Those ecosystems are naturally regulated by fire. Of course, with fire suppression, we now as humans prescribe fire. We implement those burns, and those fires can happen at any time of the year. And so one of the things I'm interested in looking at is how these fire regimes and the timing of fire affects these. That's of course, something that happens elsewhere. You have a fire. That happens in the prairies in the Midwest, but the timing of the fire and the way that fire is implemented is pretty unique. The year I think another maybe unique challenge in Florida is invasive species. So there are a lot of invasive species in Florida, both insect and plant. So how do invasive plants change the ecosystems for bees, there are a few invasive or exotic bees that have naturalized in Florida. For example, the green orchid bee. So how those change plant pollinator interactions and affect these is another I think, interesting. Certainly, there are invasive species elsewhere, but because of its position, Florida is kind of particularly susceptible to invasive. So those are some of the challenges in terms of crop pollination. The floor is also pretty unique. It's very diverse, with a lot of specialty crops, a lot of pollinator-dependent crops, and. That, you know, maybe isn't necessarily a challenge for bees, but is an opportunity to study some unique aspects of pollination ecology because we have such a diversity of specialty. That's here.

Speaker 1

It's funny, we started off. It was like Florida and Oregon is so different. But Oregon also has a huge specialty crop. We've got urban encroachment throughout. We've got forests that burn and pollinator communities that are there. Wow, we are. We are joined at the. Hip. It's nice.

Speaker 2

Yeah, it's true.

Speaker 1

But we don't have any orchid bees.

Speaker 2

Yes, that is. I know you're right, a lot of a lot of the crops that I've been working with started to work with are ones that you have up there. So a lot of the same specialty crops. I guess one difference is that in the very southern part of the state, we have some tropical crops like mangoes that you're not. Going to find a lot of them. Those crops are really just in that very kind of small. Swath around Miami so Gainesville is located more in the northern part of the state, so a lot of what we have, like strawberries, blueberries, and melons. You know, you probably have those in.

Speaker 1

We do and it, but it does. It does strike me that there are these commonalities, you know, where people go to settle and you've got this force. Well, anyway, I'm. I'm surprised. OK, well, this is really great. And I I'm also the one thing that's really interesting about your position. You have an extension appointment. And there's this really wonderful, prestigious long tradition of honeybees. Invention at the University of Florida. Can you tell us a little bit about your new program and how it sort of overlaps or is different from the current APA culture program?

Speaker 2

Well, my program, I've been in this position for about a year, so I'm still figuring out exactly my target audience. But one thing I did when I first started was to reach out to stakeholders and county extension and figure out what some of the needs are for extension related to my position of native wild bees and pollination. Ecology and right now, I'm focusing primarily on growers of specialty crops and other stakeholders within that specialty crop industry, primarily blueberries and strawberries and also potentially melons and the other kind of focal group or target audience is gardeners, in particular master. Gardeners, but can also be garden clubs and even conservation organizations. So my my main goals are to enhance crop pollination, but also to enhance resources for bees and to provide best management practices for bee conservation in public and private. Plans. And so those are the groups that I work with and it's pretty different from someone who's honeybee extension and works with with beekeepers. I think one big difference is just that they have maybe a more identifiable audience. You're going to be working with the beekeepers and for me in my position, there are a lot of different groups that are interested in or affected by in some way, shape, or form, other pollinators and pollination, so they're maybe not one kind of clear audience. You know, I also think to some extent I probably get less. Type check out my hives. What's going on? Things are dying. It's it's more kind of general interest and concern and people wanting to do things, certainly from the specialty crop growers. I get some urgent questions about pollination, but I think compared to the honeybee extension program. I may have to generate interest. I have to kind of work a little bit harder to get people invested, whereas the beekeepers, they, their livelihood is at stake. So there's maybe a little more urgency there. But you know, I think day-to-day two, my extension appointment, it's a smaller part of my program. So I do some extension, but I do a lot of other stuff, and the doctor, Jamie Ellis, who does honey Bee extension, his appointments mostly extension. So it's a bigger, bigger part of his job.

Speaker 1

It's it. What you said though makes. A lot of sense as as somebody else who's in pollinator health extension, there is a way in which you do have to have a lot more stakeholders and trying and some of them may not have very much in common yet they're they're all managing land.

Speaker 2

Yes, definitely. Right. And you've got people that are managing small amounts of land that are just homeowners or gardeners and then you have people that are involved in restoration. You have foresters, you know, there's a lot of forestry here in the. Southeast. So. A lot of different landowners manage different tracts of land, sizes of land, and types of land. So it's pretty diverse. The first group and then of course you have the the specialty crop growers that are also managing land but in very. Different ways.

Speaker 1

OK, so I just want to circle back to the crop pollination part of it. And I guess you know, 20-30 years ago people really thought about honey bees and there was like a hard sell to try and get honey growers to sort of bring colonies onto their land. But this is a different time now and I guess there's a lot of interest about incorporating native. Fees into commercial crop pollination. What are some of the real opportunities for doing that in Florida?

Speaker 2

I think again the three crops that I'm focusing on, which are more specific to maybe the Northern 2/3 of Florida melons, strawberries, blueberries, certainly from melons and blueberries. Growers know that they need insects for strawberries. I think one opportunity for increasing pollination or even increasing the role of both. Manage and while pollinators in that pollination is to evaluate, to what extent yields are limited by pollination, a lot of strawberry growers don't bring in bees. They're just relying on what's happening. Naturally, the natural insect's community. And they don't really know whether the yields that they're receiving are limited by pollination, or whether yields could increase with pollinators. So I think that there's an opportunity there to potentially boost yields or to evaluate whether yields could be boosted through better pollination. And that includes managed pollinators, but also certainly. By wild pollinators, now they're relying almost exclusively on the wild pollinators. And I think in blueberries it's a little bit of a different story and it's pretty interesting there. So blueberries in Florida, the cult of ours that we grow have been bred to bloom quite early. And so in many cases, they're blooming, blooming right now, and they're blooming in a period where there's not a lot of bee activity there. Fairly short overwintering period here, but there is a little bit of lull and activity. Do get freezes. So they've kind of been decoupled the plants and the pollinators and so this has increased reliance on managed bees. So growers bring in managed fees. But that being said, we do see some bumble bees and we also see the southeastern blue. Very be I think that there may be ways. That grower could.

Speaker 1

Wait a second. The southeastern blueberry bee.

Speaker 2

Yes. Yep. Also, yes, it's it's a beautiful bee. It actually looks a bit like Bombus. Impatient.

Speaker 1

I want to hear. About that.

Speaker 2

I mean eastern bumblebee, so it's not as hairy but otherwise it looks quite similar and it's a really excellent pollinator for blueberries. It's it frequently visits blueberries. It'll visit other related species as well, but it's a really great pollinator and it's quite abundant in Florida. So I believe in other blueberry-producing regions, especially like Michigan and the Northeast. If it's there, it's it's found in pretty low numbers, so they have found it further north, but it's just not very common. OK. Really increases in frequency as you move into the southeast. So growers in Georgia and Florida could be receiving a bit of pollination from this beef. We need to figure out can we, can increase populations of both bumble bees and the southeastern blueberry bee and if can we increase their contribution to pollination because they're out there, but in part. I think because of the timing of the blueberry bloom, but also maybe in part because of Land Management or another factor. The growers are relying pretty heavily on managed honey bees, so I think there's an opportunity there to increase pollination by other bees, but it might not be real easy.

Speaker 1

Have there been some of the growers already before you arrived there started to try and experiment with getting the numbers up?

Speaker 2

No one has, to my knowledge, done a whole lot of work with that, certainly in the way that at least growers haven't implemented. Flower strips. There was a research project that you participated in where they did look at the. Value of flower. Strips and this was before I arrived, but I am pretty sure their conclusions were just that. The present flower strips the implementation of did not increase the southeastern blueberry beer or other pollinators in blueberries. I have heard some growers say that they put out. Nesting habitat for bumblebees, so they put out upside-down flower pots that have holes in the top and are filled with dirt. And you know, I don't know how, how successful that's been. So there's maybe been a little bit of either research or management by growers. But I think by and large growers just rely on those managed honey bees, some do bring in managed bumblebees. Other than the managed bumblebees and honey bees, there haven't been a lot of efforts to increase contributions by the wild.

Speaker 1

Bees. Well, let's take a break. I wanna come back and hear. I know you're a year in, but I'm sure you've already got a lot of ideas for research projects and research projects that are underway right now. So let's it would. Be great to get it. A little glimpse into what you have planned.

Speaker

All good.

Speaker 1

OK. Well, welcome back. It sounds like you've got the start of a really diverse and incredible research program. Can you tell us a little bit about some of the projects you have underway and some of the, you know, key questions that you're hoping to address in the next couple of years?

Speaker 2

Sure, my program is aiming to be relatively diverse, as you said spanning crop and non-crop habitats. In general, I think the two main themes are pollination, ecology, and plant-pollinator interactions. So some of the questions that I'm interested in are a little bit more specific to plant pollination biology and how plant floral traits affect plant-pollinator interactions, and then the second area is more wildly community ecology. So how do you disturbances and land? Management affects communities. These so along those two lines, one of the projects that we're starting is in blueberries and I'm interested in the pollination ecology of blueberries. For one, just evaluating how dependent some of these modern cultivars are on insect leaders and also how pollen. Committed they are. So how much can we increase yields by improving pollination? And then I'm also interested in variation across cultivars and variation in their attractiveness. Pollinators. So there's kind of anecdotal evidence that some of them are more attractive to bees than others, and I'm working with the blueberry breeder. We're trying to kind of identify what some of those traits might be. One long-term goal would be to breed blueberries to make them more attractive to bees or other pollinators. Although it's mostly bees. More on the management side of things trying to figure out again how we can improve pollination so we don't have a lot of recommendations for growers here in Florida. We are relying a lot on recommendations from places like Michigan North. Oregon. So even just stocking densities I mentioned earlier that growers. These are both honey bees and bumblebees, and they're not sure at what densities they should be using these and do they complement one another. So figuring out those questions for the growers and then another big question that I find interesting is planting design. And whether we have mixed cultivars and blocks, or even within rows, and RB's moving across these cultivars, depending on the planting design, and I think blueberries offer a new system to look at that because many growers are now moving to potted blueberries so they can kind of easily. Maybe relatively easily move them around. It's probably not that simple, but they're they're putting blueberries out in pots. Yeah, yeah. So they're not putting them directly in the ground. A lot of the growers. So I might be able to more readily change the arrangement and we can also more readily study that so we can create manipulations of of cultivars mixed cultivars within blocks and rows and, look at how that affects cross-pollination and and bee movement. So those are some of the things I'm I'm interested in in blueberries specifically.

Speaker 1

And those are all interesting. You know, I I've often, you know, I think people often when they think about pollenizers, they're thinking about fruit crops. But I mean tree. But they're, you know, some of these cultivars may have some level of incompatibility, and I don't know out here it's just one block of one kind of blueberry.

Speaker

Right.

Speaker 2

Right, right. Yeah. And some of the previous research has shown that, yes, there is a degree of self-incompatibility, but it does vary. So some cults of ours are better at self-pollinating than others. Of course, you still need bees to release and deposit that pollen even when they are self. Accountable, but a lot of the more modern cultivars are supposedly more self-incompatible and growers are told they could plant them in bigger blocks. But some growers aren't getting the fruit set that they might expect and are wondering whether that's true. So I think I think doing some experiments to look at that would be really interesting, especially in older parts. Of the farm, a lot of growers do have cultivars alternating every other row. Maybe plant 2 rows of 1 cultivar and one row of another. So at least in the past, they were told to mix it up like that.

Speaker 1

That's fascinating. And the other one is the attractiveness, I know. So there's some cult we have some later cultivars here in Oregon that bloom, coincidentally, with some of the blooming trees. And it's really hard to keep the bees on the blueberry.

Speaker 2

Yes, right. And that I think is something that growers are concerned about here too. You know, being new to Florida, I don't know exactly what flowers. At the same time, especially because blueberries have been bred to bloom so early in Florida. They get a much higher price for those early berries, so they're the Breeders are pushing earlier and earlier. Varieties. But I think some things do bloom as early as January and February in the surrounding landscape and that's something growers are concerned with how do we, how do we keep the bees on the blueberries?

Speaker 1

And you also mentioned in the first segment that you're interested in these communities in forests. What are you thinking about doing there?

Speaker 2

Yeah. So I. I started collaborating with the Fire Cola. And she's interested in managing these early. Habitats and a couple of the the management tools that are used in these early succession habitats include fire and prescribed fire and I mentioned in Florida that fire can happen at different times during the year. So it can happen in the winter. It can happen in the early spring. It can happen in the late spring. And so we have an experiment set up where we have plots. They are burned at different times. Times and I'm interested in looking at how the timing of fire affects the phenology of plants and also pollinators, and how that affects their interactions. She also is looking at the management of some early successional weedy, invasive plants. And so we're going to be looking at how removal of those plants affects flower diversity and abundance and thereby affects pollinator diversity and abundance. So can we improve the diversity and abundance of floral rewards for pollinators by controlling some of these early successional wheaty species that take? So the the. The goals of that project are sort of twofold. To look at fire disturbance specifically the timing of the fire and how that affects plant-pollinator phenology and interactions, and then also looking at management of these early successional species and how that affects flower abundance and diversity.

Speaker 1

Estimating you know one other thing that you mentioned previously is you have this big group of Master Gardeners and people gardening in Florida must be pretty like a big occupation.

Speaker 2

Yes. Ohh it's. Huge. I mean, I didn't realize when I first moved down here. It's like everyone. Well, not everyone, but many people have landscape service and you know, coming from North Dakota like, no. 1 hires landscapers. So but but and the yards are just incredible. Those yards are really beautiful.

Speaker 1

So tell us a little bit about some of the work you're doing associated with the green industry and growing things in people's backyards.

Speaker 2

Sure. So I've been doing a lot of extensions as you mentioned with Master Gardeners and and one thing that's become pretty clear. Is that? We only have good lists of plants for native wild bees in Florida. There's a lot more information available about butterflies and hummingbirds, and I think there's a longer tradition and history of gardening for butterflies. So I'd like to help develop that and I've started working with a few faculty members in environmental horticulture and we're going to be testing some of these popular ornamentals as well as wildflowers. Many of these are marketed as pollinator-friendly or V plants, but they haven't really been tested, so we're going to be looking at them. They're relative attractiveness to bees, specifically bees. In these single-species plots in addition to looking at a few different species of. And wildflowers, we're going to be looking at variation across cultivars. So I guess that's it in that I kind of have in both agriculture and non-agricultural systems out of these floral traits vary across cultivars, even within a species, and many of these plants like pentas, zinnias, lantana. There are just so many different cultivars and the diversity of floral traits is pretty interesting.

Speaker 1

It does.

Speaker 2

So we're going to. Yeah. Looking at that too.

Speaker 1

No, it does remind me of an earlier episode we had with Emily Erickson in Penn State that there is this kind of way in which plant breeders have maybe created a whole host of different. It allows us to ask some questions about fundamental questions about, what makes a plant attracted to pollinators.

Speaker 2

Right, definitely. And one of the species that we're studying here or one of. It's it's, it's really multiple species, but one of the genera that we're starting is studying is lantana and lantana. There are a few sterile cultivars so these have been developed to be less invasive, but they are are sterile and I don't think they produce much pollen or maybe. And they certainly have different floral traits compared to. Some of the non sterile. Cultivars so I think that that could be interesting to look at also.

Speaker 1

Oh, same out here in Oregon with butterfly Bush. You can't grow it here. It's still there. Varieties. It's like, you know, how does that affect pollinators though? Yeah, that's.

Speaker 2

Right. Yeah. Yeah. I think that would be really interesting.

Speaker 1

Like a great question. Wow, you have a lot going on. It's really impressive. It's and I can imagine just trying to keep up with all the all the demands in Florida. We'll keep you busy for the next little while.

Speaker 2

Yeah, yeah, yeah, it is. You know, there's not not a lot of people doing work specifically on crop pollination or on native wild bees. And these non cropping systems. So there's a lot of opportunity, but it is true that also. It's great to have that diversity, but we also have to keep up with all the different projects so.

Speaker 1

Well, let's take a quick break. I've got a couple of questions I want to ask you. We asked all our guests the same questions.

Speaker

There we go.

Speaker 1

OK. Well, we're back and I asked all our guests if they've got a book recommendation for people listening.

Speaker 2

So I really like the bees in your backyard by little. Girl, I think that's a really great book because it's, you know, it's not a textbook, but it's also maybe a little more advanced than some of the other books on the topic. I think it provides some really great information about identification, which people. Often interested in and don't really know where to start. You know you don't want. Start with maybe discover life or some big key. So I think it's got some great information about identification, but then it also has some conservation information in.

Speaker 1

There as well. Yeah, it is a really and and and the images and the writing. I think we've we've had other guests, but I always was struck by how well it's just composed. Like you can pick up you can flip to any page and read it and you you're. You can follow.

Speaker 2

Yes. Yeah, I think it's. I I really think it's very well. Done. I really like it.

Speaker 1

Fantastic recommendation. Next question we have for you is if you've got a go to tool for the kind of work that you do.

Speaker 2

So this one is a little bit tricky, but I think I would say that again as as someone who in addition to will be community ecology is really interested in pollination ecology and pollination biology. I, I might say pollinator exclusion bags or. Mesh, I think that's. What I find myself using most frequently. Actually so.

Speaker 1

OK, describe these things.

Speaker 2

Yeah. So that you you can use different materials and it's a little bit on the plant you're working with. It can be a very small bag of lightweight mesh that excludes pollinators. It could be a a medium sized to large bag if you want to cover a whole branch or I might even include in that category some kind of. Each made of light mesh that could exclude pollinators from an entire tree or an entire Bush, and we've used all three. We've used small bags, bags that cover more like whole branches, and then even large cages that will exclude pollinators from larger areas.

Speaker 1

I've always thought that these could be really well used in like a school garden program, but I imagine for if there were was an educator out there, it's like ohh I wanna show my students the effect of pollination by excluding some flowers. But I don't know where to get these things. What would you recommend to them?

Speaker 2

Ohh that is a good question.

Speaker 1

Do you make do you? Make your own.

Speaker 2

I don't. I think that most of the ones that we've gotten have actually been. So there's sort of two main sources. One is just garden stores, including online garden stores. So you can use just general insect exclusion. So for example, some of them are like no thrips, they're sold as no thrips. Bags to exclude thrips. So often you know garden garden stores, online stores or or ones that you can drive to will have. Things like this, but there's. Also, a company I believe it's called Del Star that sells specifically these sort of pollinator exclusion bags and that's where we bought them in bulk. And so that and you can. Order them online so that would be another source. But you know, I think you might have been able to use just like row cover. So that kind of gauzy, very lightweight white mesh that you can buy at any garden store or even like a home improvement store like Home Depot or Lowe's might carry it. And typically you use it to cover whole plants or rows to prevent pests. But I think you might even be able to use. That I've never. Used that so I. Don't know how the light intensity, you know one question is always how does it affect the light intensity and moisture and things like that? I've I've never used that. Gauzy row fabric or mesh, but you know that's maybe a.

Speaker 1

Possibility, but the idea is if you had a blueberry branch or something, you would put it on before the flowers open and then they would set. Fruit and take it off and then you would measure it, I guess to a branch that you didn't do that to.

Speaker 2

Exactly. Exactly. Yep. Yeah. So you have somewhere you've excluded pollinators and others where you haven't and. You know, if you can keep the bag on for as little time as possible, that's good because again, it could have effects on light intensity, moisture, humidity. So often we put it on right before bloom and then we actually take it off right after bloom. But we keep the little branch flag so we know where we put the bag.

Speaker 1

Ohh right, that's the bags gone. Like, where was it? OK.

Speaker

And then you.

Speaker 2

Can compare that to. To another branch.

Speaker 1

OK, that that's a great recommendation. Thank you that you're the first pollinator exclusion bag recommender in 80 episodes.

Speaker 2

Wow. Oh, that's interesting. I guess I'm revealing my my I'm moving more in a plant direction. I think as I. Go along so.

Speaker 1

Oh, these three questions. They're about revelation, yeah. And the last question we have is, do you have a favorite pollinator species?

Speaker 2

Yeah. So I I thought a little bit about this one. And again, it's kind of a a tricky question because I I think it changes overtime as I work in new systems. But right now I am really into the southeastern blueberry beef. So it's it's it's really beautiful, it's really. Abundant enough that you know you can, you can study it. You notice it out there, but there's still quite a bit about his biology that we don't know. Jim Caine published some some great papers a while back on it, but I think there's still a lot that we don't know about it. And it's it's really fun to watch. It's fun to watch it visiting blueberry. Flowers. So I really like that one. Back when I was in North Dakota, I worked a little bit with this. It's sometimes called the sunflower leaf cutter bee Mega Kai. Leaf lunata or?

Speaker 1

Oh yeah.

Speaker 2

Cutter beak and. It's just really cool looking. It's really beautiful, especially the males of that species. So that's that's another favorite.

Speaker 1

Fantastic. We'll we'll link those up on the show notes and also you can learn more about Doctor Mellinger's program. We'll have links there. Thanks so much for taking time out of your busy schedule to talk with us. On pollination.

Speaker 2

Yep, you're. Welcome.

Speaker 1

Thanks so much for listening. Show notes with information discussed in each episode can be found at pollinationpodcast.org constate.edu. We'd also love to hear from you, and there's several ways to connect. For one, you can visit our website to post an episode. Specific comments suggest a future guest or. Topic or ask a question that can be featured in a future episode. You can also e-mail us at pollination podcast at oregonstate.edu. Finally, you can tweet questions or comments or join our Facebook or Instagram communities. Just look us up at OSU pollinator health if you like the show, consider letting iTunes know by leaving us a review or rating. And makes us more visible, which helps others discover pollination. See you next week.

Oregon and Florida may seem miles apart, but the role of bees in both states has remarkable parallels. This week Dr. Rachel Mallinger University of Florida talks about blueberry pollination, bees in forest systems and interests of gardeners around bees in the Sunshine State. Dr. Mallinger is a professor in the Department of Entomology and Nematology at the University of Florida. Her position is 60% research, 25% extension, and 15% teaching, so she wears many hats! In general, she conduct research on pollination ecology, plant-pollinator interactions, and wild bee community ecology. Her extension programs works with growers of pollinator-dependent specialty crops (e.g. blueberries, strawberries), and with Florida’s Master Gardeners to improve gardens and landscapes for native wild bees. She also teaches a course on the ecology and conservation of pollinators for both undergraduate and graduate students.

You can Subscribe and Listen to PolliNation on Apple Podcasts.

And be sure to leave us a Rating and Review!

Links Mentioned:

Dr Mallinger’s Book Recommendation: The Bees in Your Backyard: A Guide to North America’s Bees (Wilson and Carril, 2015)

Go to tool: Pollinator exclusion bags (here is an exercise using these bags from Ohio State University – also here are the bags that Dr. Mallinger uses)

Favorite Pollinator: Southeastern blueberry bee (Habropoda laboriosa)