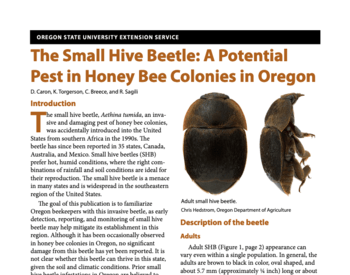

Transcript

Speaker 1: From the Oregon State University Extension Service, this is Pollination, a podcast that tells the stories of researchers, land managers, and concerned citizens making bold strides to improve the health of pollinators. I'm your host, Dr. Adoni Melopoulos, assistant professor in pollinator health in the department of horticulture. I'm really pleased today to welcome Dr. Lynn Royce to Pollination.

I know if you're an Oregon listener, you know Dr. Royce. You probably had a lecture from her at one of your bee clubs, or if you're in the Oregon Master Beekeeping program, she was likely one of your instructors. She did a lot of research on honeybee parasites and breeding for resistant bees. More recently, you may have seen her at a table for tree hive bees, a company she runs that produces bee colonies that mimic the natural condition of bees living in trees. That's what we're going to talk about today, is bees living in a natural condition in tree hollows.

There's going to be a really great part, midway in the episode, where she describes this technique called bee lining, where you can take bees and you can trace them back and find their home in the forest. I just want to also make a shout out, we are always looking for ideas for shows from you and or questions about pollinators. We'd love to do an episode on questions from our listeners. Please follow at the end of the show. We've got ways for you to contact us. We'd love to hear from you. Without further ado, let's launch into this episode of Pollination.

All right. I am so excited. Across from me at the table, I have Lynn Royce. Welcome to Pollination. Thank you. It's good to be here.

It's great to have you here today. We are in a cavity today. We're in my office and we're going to be talking about honeybees and cavities. In previous shows, we've talked to people about native bees and their preferences for cavities, but we don't often think about honeybees inhabiting natural cavities. This is kind of, it's interesting and curious. We think of them in boxes and out in fields. We don't think of them in natural settings. Can you tell us a little bit about that? Like what kind of a natural cavity is a honeybee looking for?

Speaker 2: Honeybees look for cavities that are not too big and not too small. And they generally find them in trees. Don't think we know out here which trees they prefer, if any, or if it's just a cavity that's available and size is good for them. I've seen them in cavities that are way too small for them and those bees did not look like they'd make it through winter, but maybe it was all they could find in the forest. They were searching for cavities and I don't know.

Speaker 1: So what kind of size are we talking about? What does what would a honeybee colony really like for size?

Speaker 2: They're looking for a space that's about 10 gallons. Really? Okay. So, the ones I have seen in our Douglas fir trees, which I don't know what they would ever encounter very often in other parts of the continent, but those have been smaller, and hard to know how well those colonies do.

Speaker 1: How does one get? Like when I'm looking around, I see a cavity, where does a 10-gallon or something like that size hole appear? Like woodpeckers, how do these holes appear in forests?

Speaker 2: That's a good question. I don't think we know the answer to that in particular. It looks to me like probably something happened to the tree trunk or a large limb or something that damaged the tree so that there is a hole through the bark to the wood of the tree and then whatever comes in after that, be it ants, woodpeckers, fungi, make the cavity bigger until it's big enough for bees to inhabit.

Speaker 1: Okay. And so how do honeybees find these holes? If they're hard for us to find, how are they finding these holes?

Speaker 2: I'm assuming they just go out and look for them. I'd fly around if they come to a tree that looks big enough. There are a lot of things we don't know about how they perceive stuff and why they would look at a particular tree or another, but they do find them. And I would love to know Tom Sealy has done the most work in this country. Right, yeah. And he has an average of about 29 feet, I think, above the ground, which is fairly high.

Okay. Here it might be more because if they are in primarily dug for forests, the cavities I've seen were above 29 feet. One was about 50 feet high or a little more than that.

But those cavities were smaller. I'm expecting and I could get totally wrong because what I know of the forests and the bees out there is minimal at this point. But the tree species are quite different here from the east coast.

Speaker 1: Right, Tom Sealy is in Cornell, so this would be like a New York hardwood forest. More likely, yeah.

Speaker 2: They do have evergreen trees, but I don't think there are as many and I think some of the hardwood forests, that's it, they're hardwoods. Okay. You know, like our oaks and our maples, I think they are going to have bigger cavities than the Douglas fir. So I don't know if the bees can sort trees or not. I'd like to look at that too.

What an interesting question. I'm really hoping to start a citizen science project, so I need to work with somebody who's done that before. I'm not sure how to set up a site for people to go to and report things that are going to be reasonable reports.

Speaker 1: Finding people who, so when people come across.

Speaker 2: Nests in their cities, nests in their backyard, nests in their forests, if they can give me tree species and hide above the ground in as many parameters as we can get. You know, it is citizen science and we would have to take it for what it's worth, but it could give us some really good ideas.

Speaker 1: All right. So getting people to kind of report these, the kind of conditions, where the bees are and what kind of trees they're in, but just a real basic question. Why would a bee colony want to be 29 feet near? Is it, is it, that's the, is there an advantage, do you think, of being not right at ground level? Honeybee colonies, we usually keep them right on the ground.

Speaker 2: Yes, we do. You know, when we took bees out of the tree and put them on the ground in our boxes, we changed every parameter that they have evolved over the years. So you can have me talk for hours on this because it really upsets me. We're all like, oh, it must just be the mites. Oh, it's, you know, the weather's changing or whatever. But we put bees in big groups and we just talked about yellow jackets a little bit earlier and they find the bees because they're in groups and the smell is stronger. We also introduced the bees to yellow jackets. They didn't have yellow jackets that didn't go up the trees to find beehives or insects.

Speaker 1: They generally hunt on the ground. So when you have honeybee colonies on the ground, yellow jackets can find them much easier than if they're way up. You betcha.

Speaker 2: But do the bees seek to be way up? I don't think so. I think that's how the cavities come for the most part. I have seen cavities in trees that the bees enter and depart from a hole in the ground. And I've seen them everywhere in between. But I think on average, most of them are mini feet above the ground so they don't run into bears. And I know that there are these wonderful cartoons of bears reaching into a bee hollow or tree hollow to get the honey. But, you know, for the most part, those holes are not very big and the bears would have an awful hard time opening them bigger because they're hanging on with three feet.

And Brian went in there strong. I grant you that. But when you have an outside diameter of seven inches for the most part and maybe down to two inches where an entrance is, that's really different from what we put the bees into on the ground. All right.

Speaker 1: Well, take us in one of these hollows. What if we were to look inside? What would we see? I mean, we think about frames in a honeybee colony and sort of spaced out. How does it look inside one of these natural colonies?

Speaker 2: It's very uneven. It's not smooth and shiny like the wood that we processed and made boards out of. It's generally they coat the entire inside with propolis.

Speaker 1: So you will look on the surface and it will be covered with pros, but it's all uneven.

Speaker 2: And there are small holes that they don't cover. Yeah. The frames hang from the top down. Yeah. They may be shaped really funny because they might be going around a piece of wood that didn't rot away. So it's still still there.

Speaker 1: Is it always anchored at the top or do they pretty much?

Speaker 2: And I don't see a lot of it being anchored at the side, but I am new at this. And so I haven't looked in a lot of tree hollow colonies.

OK. This size is usually smaller, which means the bee's colony is going to be smaller. The shape of the tree hollows is generally such that you have a space above the colony and a space below the colony. The space below the colony is usually full of debris, probably from the hollowing event, whatever it was, whether it was ants dropping sawdust or termites. Some of these dug for trees that looked like termites were the first inhabitants of the hollow or a woodpecker. It might be smoother if a woodpecker did it, but a lot of the woods going to fall beneath the hollow.

Yeah. And then up above, often you're running into the tree, you know, becoming more solid as you get away from this bit of rot that has happened to the center. And that space may be really important to help with humidity control and

Speaker 3: airflow and, you know, stuff like that temperature. In fact, there's a paper and I haven't gotten my hands on it yet that says that if a colony can maintain a humidity above 85 percent, now this is not moisture in the air, this is humidity. So we create in our wooden hives a situation where the water is high in the air and it goes up and comes down as rain inside the colony. Right.

Speaker 1: It condenses and drips on the bees. But in a tree hollow, this doesn't seem to happen. And I think it's because they can maintain a good humidity, but it doesn't become whatever that is. Right. So the mites that we have problems with are their original host is Apisurana. Apisurana is a tropical bee.

Speaker 1: And another cavity-nesting honeybee.

Speaker 2: And another cavity-nesting honeybee. And their cavities, don't have a problem with having dryness. So they have this high humidity that they can maintain in the cavity and the mites don't do well. So at, I think it's at 85 percent, the mites, only five female mites per or five percent of the female mites will reproduce at below 85 percent. You get a higher. So 53 percent below 85 percent humidity, 53 percent of the mites will reproduce. You can see the difference there.

Speaker 1: You know, I remember there was this really nice study that John Harbaugh and Jeff Harris did when they were selecting. Might resistance. Yeah, the Varroa sensitive hygiene and they would run these colonies every year. They'd make a package to stock them with mites. And then they noticed that the growth rate was none even. And so they correlated it out.

And it was exactly as you said, when they had these colonies that were really dry, seasons that were really dry, mites didn't seem to do very well. And so it had this, it had this effect of we're saying the same thing, right? Right. Yeah. So it had this effect of, you know, these conditions, and they were thinking about your conditions, but it does raise your question of like, well, if a colony had these more natural parameters that they find in a natural cavity, that that might, you know, really buffer them and create the environmental conditions that are not really that conducive to past problems.

Right. We've talked about the advantages of being in a tree for a honeybee colony. And you've also mentioned that here in the Pacific Northwest, one can find honeybee colonies that have, you know, escaped the beekeeper's purview and have gone back and become feral colonies.

We talked a little bit. And I noticed you have a blog post on your website about bee lining, which is a really fascinating procedure. Can you tell us a little bit about beelining and how one goes about finding these trees of bees that may be kind of hidden in the forest?

Speaker 2: Sure. And it's going to be different in every environment. You do bee tree hunting. Okay. In the forest we have here in the Pacific Northwest, you have to watch out for other things while you're bee lining, as it were, yellow jacket nests. We talked about them a little bit, but there tend to be a lot of yellow jackets in these forests underground and you don't see them as you're whacking through the brush.

Speaker 3: That's a real danger. And then there's always bear. And I kind of kid around with a timber cruiser whom I know and who has helped me out a little bit. The bear we would know was attacking us, but if we get attacked by a cougar, we'll never know.

Okay. And both those critters live out there. We did run into a bear last summer. She had a cub. Fortunately, my volunteer scared the cub so the mama went away and didn't attack him.

Speaker 1: I like how you've prefaced this, Lynn. Is this like, okay, for listeners out there, this is not for the faint of heart. No.

Speaker 2: And when you read, I love Tom Sealy and don't misinterpret this, but when I read his book on bee lining, it's a great book and has a lot of information about bees and how you do this and it goes step by step. But it sounds so simple.

When you get out there in 100-degree weather the sweats are dripping off your nose and the light is too bright and you lose the bees because they go up into a brightly lit sky and disappear into the sun. How do they do that? I don't know.

Speaker 1: Okay. So walk us through this procedure at least step by step. How it works in theory.

Speaker 2: All right. So get away from the machetes and the yellow jackets and the bears. So basically you set up a station where there are a lot of nice flowers. Okay. And you, if the bees, you catch the bees in a little bee lining box and it has two compartments.

Speaker 1: So the, and the box is about the size of like a volleyball or something smaller.

Speaker 2: It's pretty small, small enough to fit in your hand and you can adjust it to fit your hand. You can make it bigger if you have big hands and smaller. Okay.

And the book does describe and gives you dimensions and I took it to a carpenter to get ours made and he changed it a little bit because he likes things to be his own. Okay. And that's fine. But you basically have one chamber and you have a door in between that you can pull out. Yeah. And put back in so you can and one end has a glass or plexiglass end to it.

Yeah. And you have another door behind that that you can pull in and pull out or open and shoot so that you catch them in the front chamber that's dark.

Speaker 1: So two is two, they got two chambers and it opens up and then you do you put the bee in like your right.

Speaker 2: So you have this box with a door that closes. Yeah. It flops up, flops down and you can lock up with a little hook screw. Gotcha. So you catch a bee in that chamber with the box. You walk up to the flower and go, whap. Got it, got my bee. And you got a bee in there.

And, but you want to catch more than one cause you're going to feed them in there on a bit of honeycomb with a nice syrup and you want them to love it. So you sent it with something so they'll come back. But you want to send more than one out. So you want to catch more than one. So you've got one in your front chamber. And obviously, if you open that door, she's gone like a shot.

Gotcha. So you open the door between the two chambers and you open the back door so that light comes through the window and she'll go to the light. OK. And then you shut the doors again and you catch another bee. And you got there. So you can catch up to six or seven bees.

Speaker 1: So the doors are acting as a way to kind of, it's like I was going to use a Star Wars metaphor, but forget it, let's not do that. So you open it up, you open the door up, and then all the bees kind of, the bees sort of move to the back chamber. You close it and then you get your next bee. So you can, it allows you to aggregate bees. Right. Gotcha. OK. So yeah.

Speaker 2: And you have to make sure that there's no way for the bees to escape when you open the door to the back chamber.

Speaker 1: OK. You got a lot of bees now. They're feeding on this delicious comb.

Speaker 2: Yeah. So you have them all in the back and you fill the comb with nectar and you or honey or sugar syrup, sugar syrup with anise was Tom's favorite. Uh-huh. And you set it in the front chamber, shut all the doors, open the door between the two chambers, and cover it with a dark piece of cloth.

Gotcha. The bees don't get distracted by light coming in from any direction. OK. And they feed on the honey for the nectar, sugar, or whatever for five minutes or so. Uh-huh. And then you let them go.

OK. You don't mark them yet. You let them go and they circle around and you try to follow them. So that you can get a compass bearing on the direction they finally go out.

OK. And they're going to circle up quite high before they take off, usually because they're confused now and they need to get their bearings on where this wonderful sugar syrup was so they can come back to it. And you can't follow them all. But you might get a bearing on one. OK. And then you sit there and you wait. OK. For the bees to come back. And she's going to go back with her load of sugar. And when she gets back to her colony, she may dance for a little bit. And then she may unload her nectar and she may dance more. She may talk to other bees and then she may rest.

Speaker 1: I can't imagine the story. I was I was sitting on this flower and then this box closed on me. But then there was this delicious stuff and I tell you, you got to try it. Right.

Speaker 2: So this is how you get there. So you hope that she does do a dance and she will send some other bees back. So you sit down and you put your box right where you let them go. Yeah. And you set the comb a little bit out of the out of the front door.

Yeah. And then you wait. And it could be 10 minutes, five minutes, shorter the time. And you write the time down that you open the box.

Yeah. You know, you have the time. So you know how long it takes them to go and come back.

And you write that down and you just have all these parameters that you keep track of. Yeah. And then as the bees come back and start to feed on the nectar, you try to mark them different colors. Gotcha. With paint.

OK. It sounds easy and you try not to get any on the eyes and the wings. And after a while, you do pretty well at it.

OK. So then you have marked bees. And then when the marked bees leave, you try to get as many directions as you have. So you have two people working. Oh, OK. Two people could say I'm going to follow blue, you follow red. And you time them when they leave and you get their direction. And if you're lucky, they're both going in the same direction or you might have two colonies that are coming in depending on how many bees you caught.

Speaker 1: So the timing gives you a sense of how far away it is. Right.

Speaker 2: So we know bees. See if I can get this right. Somebody can call in and correct us, I suppose. I think they fly about 15 miles an hour, basically. OK. So you time them coming back. So you mark them and you have to wait for the mark bee to come back before you get your really first-time distance. Of course. Right. And if she dances, then it's going to take longer. And so eventually over time, we did this a long time for the first time we ever did it. So we kept coming back day after day. So we kept marking bees and they, you know, they we would get short times. And so those were the directions that we wanted to follow. OK.

Speaker 1: So you've got one bearing and you've got a distance. How do you find the colony now?

Speaker 2: So now you move 10 feet. In the direction that your shortest bees were flying from. Yeah. And you set up again and you wait for bees to come back. And if you don't go too far, they will come back. They will find you.

Speaker 1: OK. They're like, I thought it was here, but maybe I'm wrong. It's 10 feet away.

Speaker 2: It's 10 feet away. Yeah. And so you just keep moving down that path. And eventually, you will run into really short times and you know you're really close. And so then you want to start looking for a big enough tree to have a hollow for the bees too.

Speaker 1: So like every hour you're moving at 10 feet or something. Kind of.

Speaker 2: Kind of sort of. Sometimes you wait longer. OK. Sometimes shorter. And when we got to the to where we were getting bees coming back really quickly, we were walking through a gully that had large trees in it, obviously, because it had a water source and at some parts of the year and probably was making the trees grow bigger. Plus they had maple and other trees that like water and grow big along the edge of the streams. Plus our our loggers were pretty respective of the riparian habitat. So some of these trees were big.

Speaker 1: We're big. So did you find the tree?

Speaker 2: We did. But before we found the tree, we were walking through this gully trying to figure out, well, then we want to go this way or that way. And and we were the blackberry in this area, the Himalayan blackberry grows about 20 or 30 feet high.

Yeah, cover the whole gully. And so we were whacking our way through and this bee came around, so around me and me and I go, Dan, this is a red bee.

Speaker 1: It's like, where is my box? Yeah.

Speaker 2: Where is that good syrup? You keep bringing us. I'll be darned. Yeah, it was really amazing. We didn't find the bee tree that day and we actually got distracted by some other bees that were coming back quickly to another station that was directly south of where this bee circled us. So we didn't know if she was coming from there. It was not very far from that next place. And then we we couldn't we weren't getting anywhere with that station. So we came back to the other side and we found the bee tree.

Actually, Dan found it. This is my volunteer and he went out fairly early in the morning. I think it might have been late evening, but the sunlight was coming through the trees at an angle and highlighted the wings and he could see these insects flying because their wings were reflected and there were a lot of them. Great. And he found the bee tree and it was so exciting.

Speaker 1: Well, thanks for telling us about bee lying. This is a really great example. And I and it's real. I really like the way that you set this up this is not, you know, you look at it as like, I will find a bee colony tomorrow. It's like a lot of work.

Speaker 2: It took a summer. I think we can do it faster. But this year has been very strange, hot, hot weather and flowers are different. And so we haven't haven't got into it this year. But I'd like to tell you why we're doing it.

Speaker 1: Yeah, please do. And tell us a little bit about tree-high bees.

Speaker 2: So when I realized we had taken the bees out of the trees and changed everything for them, I think they're stressed now. How can I help the bees first? And it seems intuitive that if I help the bees, I might be helping the beekeepers. And, you know, I did my honeybee research here at OSU, and I know a lot of the beekeepers in Oregon, and I'm very good friends with them. And I like them a lot.

And I'd like to help them. So how did you do this? How do I look at it? Everybody's looking at the mites and the diseases that mites transmit.

And I'm like, well, maybe we need to go back to the bee tree and see what we've changed that we might be able to get back to the bees that would help them. And I think there are a number of parameters. Some of them will not be something the big commercial outfits will want to use. But then big commercials may not be the way to go.

Speaker 1: I'm sure there's lots of people who are looking and we have lots of listeners who are just interested in keeping bees for themselves. And there are probably some really great lessons for them to pull out of this kind of work.

Speaker 2: So I'm hoping so. And I think one of the things I've learned is smaller colonies get them off the ground. So they're not so susceptible to the creatures that hunt on the ground that would love honey and can push over your little box on the ground. Like skunks and raccoons and bears. Those guys, opossums can be really devastating to your hives and it can be attractive if you're out in the country.

Speaker 1: How high do you need to be to kind of get some of those benefits?

Speaker 2: I would say at least three feet. OK. And that's high. If you're after honey, it's going to be more difficult to work with some of these parameters. But, you know, people can be inventive. And if you ever drove to the coast on 34 a few years ago, you would see these big picnic tables likes things big, though. And they were to keep the bears out of the beehives and they figure out a way to haul the beehives up to the top of these things so the bears couldn't get up there. I can't imagine keeping bees up there.

I'd get so engrossed in the bee work that I'd fall off this thing. But I guess they worked. People, I did see numbers of them. I don't see so many anymore.

I think I don't know why. I think other beekeepers have the same problem I do. But difficult, more difficult if you have a lot of bees. You know, you can't do that. And I think the way we keep bees now, we did everything to make it convenient for us, but not necessarily convenient for bees.

Speaker 1: Yeah, sometimes it's hard to think about that. It's like, oh, what do be one of the things that's come out of this conversation is interesting to me is like, oftentimes we presume that, you know, a nice white box at ground level is what they want. But in fact, if they had a preference, they might not choose that.

Speaker 2: Very likely. Yeah. Very likely. Now, one thing that Tom Sealy points out is if there's a wax in the cavity, that's the most expensive thing bees have to have. And I've heard anywhere from 10 to three times the amount of nectar to make the same amount of wax to make one unit of wax. So three units of nectar to if it's really good stuff to one unit of wax, but it's more like on average five or higher units of nectar to make one unit of wax. So it's expensive, of course, for the bees. And so if they find wax in a cavity, even if it's too small for them to be able to store enough for winter, they'll accept it because it's so valuable. Right. OK. So that's that's interesting to me that we can that the bees do have their faults, too. It seems so perfect.

Speaker 1: Lynn, we have these questions we ask all our guests, and I'm really curious what your answers are going to be. The first one is, is there a book that is influential to you or you want listeners to know about?

Speaker 2: I would say of the book and there are so many wonderful books out there that this was a really difficult decision. But I would say Honey Bee Democracy by Tom Sealy.

Great. Is a wonderful book. It's such a fun read and has a lot of lot of information. And of course, it was what I wanted to get into to look for things that we might give back to beekeepers or maybe get back to the bees.

Speaker 1: You know, you and I had a conversation before the interview. We were talking about, you know, experiments that are rooted in hypotheses. And there's something about a Tom Sealy book that is a series of experiments that are coherent. Everything's joined together. He's got a big question and he keeps asking that question in multiple ways. I it's not really anybody like him in that regard.

Speaker 2: No, he's probably one of a kind, really wonderful person. And, you know, sometimes you don't always find that in the best thinkers.

Speaker 1: Well, our second question, and also I think Honey Bee Democracy was recommended by another guest as well. So it's a popular book on pollination. We have to get Tom on the show. We should. And he'll be in Oregon. He's come through Oregon a couple of times in the next. He's here this he's coming next spring. Anyways, Tom is Tom Sealy, who was here last year and is going to back the state. Watch out for Tom. Okay.

There you go. And next question is, is there a tool that you like to use? Is it really a key tool for you working with bees or the kind of work that you do?

Speaker 2: Um, that's an interesting question. You know, I think the best tool I have is my hands. And I never put gloves on. I was taught not to use gloves as they and if you're chasing queens, there's no way to catch queens with a pair of blood.

Speaker 1: Some people on the show are native bee people, so they may not understand. So when some people wear these cow hive or goat skin gloves are pretty thick and you you can't pick things up. But I guess the other thing is that you're not attuned to the bees at the same time.

Speaker 2: This is true. And you wear them because you're afraid of the stings you're going to get. But I find that beekeepers who use their bare hands have much nicer colonies because they can't bang through them fast.

And if I had a complaint about commercial beekeepers most of their bees are really kind of cranky because they don't have time. And maybe we need to step back and take more time. And you do definitely slow down when you have bare hands.

Speaker 1: All right. So Lynn's tool is the ungloved hand. Yeah. Okay. A last question for you is do you have a we ask people what their favorite bee is and they answer this in all sorts of ways? Is there a bee or bee colony or something that you want to highlight for our guests?

Speaker 2: Well, I have to say the coloration and the uniqueness of the orchid bees in Central America have always captured my eyes.

Speaker 1: I guess. Have you seen them up in real? I've seen collected ones. When I was a grad student there was a paper out where they were treating the houses, which probably wouldn't be considered houses here, but they were the little places where people lived and slept and cooked. And they were treating them with DDT and the males of these orchid bees go to orchid flowers. The females do not and that's where they get their name orchid bee and their color is just brilliant. They're some of the most beautiful things I've ever seen. So the males that go to the orchids and collect specific scents from the orchids, some of them may be toxic and some of them may not.

Speaker 2: And that was years ago. So research has probably come out that I haven't seen because I've been concentrating on honey bees, but the scents that they collect are stored in pockets that are separated from the body. So if they are toxic, they don't contact it so much. And so they were going into these cabins and there was a lot of malaria and yellow fever and I don't know what else in that area. So they were spraying with DDT, the new cure-all for the world. And these bees were going into the cabins or the hutches and collecting the DDT off the walls. Really? And sequestering it and scientists were blown away by this. And I am too. And I've always been curious if any follow-up had been done on the orchid bees.

Speaker 1: So guess we will all the stuff that Lynn has mentioned, including tree hive bees, the website, Facebook, we're going to link it on to the show notes. But I'm going to, after we finish this conversation, I'm going to get on Google Scholar and see if I can find that study and if we can link it because that is a fascinating, amazing study.

Speaker 2: Yeah, that would have been back in somewhere between 85 and 89 when I took that class.

Speaker 1: So guess if you don't see it on the show notes is because I failed.

Speaker 2: It could be difficult, but you never know. Some of these papers show up and we have a lot of information out there now that we can use ways to find stuff.

Speaker 1: Well, thanks for taking time away from the machetes and the Blackberry thorns to come in and talk with us today. I appreciate it. Thank you. Take care. Thanks so much for listening. Show notes with information discussed in each episode can be found at pollinationpodcast.organstate.edu. We'd also love to hear from you and there are several ways to connect. For one, you can visit our website to post an episode-specific comment, suggest a future guest or topic, or ask a question that can be featured in a future episode. You can also email us at pollinationpodcast at organstate.edu. Finally, you can tweet questions or comments or join our Facebook or Instagram communities. Just look us up at OSU Pollinator Health. If you like the show, consider letting iTunes know by leaving us a review or rating.

It makes us more visible, which helps others discover pollination. See you next week.

Lynn A. Royce, Ph.D. did her doctoral research on tracheal mites of honey bees and has studied pollinators for over 30 years.

She is a passionate scientist who cares deeply about implementing research in practical applications to improve honey bee health.

In this episode, we talk about her organization Tree Hive Bees, and how you can perform “bee-lining” to trace wild bees back to their colonies in trees.

You can Subscribe and Listen to PolliNation on Apple Podcasts.

And be sure to leave us a Rating and Review!

“There’s a lot of things we don’t know about how bees perceive stuff and why they would look at one tree over another.” – Lynn Royce

Show Notes:

- Where honey bees used to live in the wild

- How the honey bee would find a big enough cavity in a tree

- How a bee colony looks like when they don’t have a man-made bee hive

- How bee-lining works

- How to catch bees in order to trace them back to their wild home

- Why she started Tree Hive Bees

- What we can learn from the bees’ natural habitat

“Maybe we need to go back to the bee tree and see what we’ve changed that we might be able to get back to the bees that might help them.” – Lynn Royce

Links Mentioned:

- Tree Hive Bees: Website | Facebook | Twitter

- Following the Wild Bees: The Craft and Science of Bee Hunting

- Lynn’s favorite book: Honeybee Democracy

- Lynn’s favorite bee – orchid bee

- Follow-up DDT study in 2007