Transcript

From the Oregon State University's Extension Service, you are listening to In the Woods with the Forestry and Natural Resources Program. This podcast brings the forest to listeners by sharing the stories and voices of forest scientists, land managers, and enthusiastic members of the public. Each episode, we will bring you research and science based information that aims to offer some insight into what we know and are still learning about forest science and management. Stick around to discover a new topic related to forests on each episode.

Did you know that the In the Woods podcast won an award? That's right. We've been nationally recognized by our peers as being one of the leaders in providing natural resources content and education through a podcast. But what do you think?

Do you like the topics we've been covering? Are there topics we're missing that you'd like us to cover? How's the quality of the episodes? We've developed a short survey where you can let us know how you feel. Head over to our website @inthewoodspodcast.org to access the survey. Or you can find a link in this episode's show notes.

The survey should only take about 5 to 10 minutes for you to complete. And when you're done, you'll have the option to enter into a drawing to win some In the Woods swag. We've got magnets, stickers, coffee mugs, and t shirts for you to choose from. We really need your help, so please take a moment to fill out the survey.

The feedback we receive will not only help with improving the podcast, but also help us in the Forestry and Natural Resources Extension Program to ensure we're reaching all our audiences. We look forward to bringing you more engaging content on a wide range of topics with guests from diverse backgrounds, experiences, and expertise. From all of us at In the Woods, Thanks again for listening.

All right. Welcome back to In the Woods podcast presented by the forestry and natural resource extension program at Oregon State University. I'm Jacob Putney extension agent in Baker and Grant counties and your host for today's episode. I'm excited to be joined by my extension colleague here in Northeast Oregon, John Punches.

John is the Extension Forester in Umatilla, Union, and Wallowa Counties, as well as an Associate Professor in the Department of Forest Engineering Resources and Management at Oregon State. He's been with the Extension Service for nearly 30 years and has a wealth of knowledge, most recently working in forest restoration, fire, and fire management.

John holds a PhD from Oregon State University, a master's from Virginia Tech, and a bachelor's from Michigan Tech. John, we collaborate on a number of programs across the region, so it's really great to have you join us for an episode today. Why don't you tell us a little bit more about your background and some of the things you've been working on?

Well, Jake, it's good to see ya, and you're right, we've collaborated on lots of different projects, so I really appreciate your partnership, but we've been here in Northeast Oregon just doing lots of work, as you mentioned, around forest restoration. I moved over here from Douglas County about five or six years ago, and it's just really clear that the pressing need in the northeastern corner of the state is around the integration of Fire management and really thinking about how fire has traditionally and historically played a really big role in the disturbance cycles in our forests.

And so now we're just trying to make our forest once again resilient to those natural fire cycles. I feel like we collaborate a lot, but I feel like I hardly see you. Yeah, lots of time on the road, lots of activities and lots of forestry training all over the place. So it's good to be here today. So, this episode today is intended to be fall themed, and if you work in the forest sector, you probably know that fall is a great time to get out and burn some slash piles.

So, piling and burning slash piles are exactly what we're going to be discussing today. To kick us off, John, let's start with the basics. So, what is slash, and why is it piled? Well, it's interesting to you and me, slash is just a common term that we use, but other folks may not know what that is. So, yeah, let's put a definition to it.

So, when we're doing operations in forested areas, where we're removing trees, and that might be harvesting them for products. It might be doing a thinning operation. It might be a fuels reduction type of project. There's some portions likely of those trees that are going to be big enough to be removed for a product that we could use, to make into lumber, to make into paper, something like that.

There's going to be other pieces, the parts that have green on them, the the branches, the ends of the trees, the tops of the trees, things of that nature. Or it could be pieces of trees that just don't have commercial value. So stuff that's partially rotten or damaged, things like that. Those get left behind and we collectively refer to that as slash.

So you can think of slash as kind of the debris left after one of those forestry operations. So it's the woody, woody residues that are left over. So those residues, are they required to be piled or what might be some motivations for piling them? Well, there's actually several different reasons why you might want to do something with that left behind slash and we can kind of put it into some categories.

So one is that that material could be something that burns in the future. So it might be a fuel source if a fire were to get started in your property. So, so piling them is one of the common ways that we mitigate that, that slash from a fuel perspective, but there's also the perspective of managing that slash so it doesn't become a reservoir for bark beetles or other things that might be attracted to that.

Um, that's particularly true in the pine species. And I'm sure you'll ask me questions about that later. So, so there's, there's also that kind of component and then finally. If you are in an area where you're relying on manually planting trees following that, that operation in the forest, well, it's just really hard to plant through that slash in some cases.

So if the slash is heavy enough to get in the way of doing planting operations, then some measure of piling it or removing it from that site, it's going to be necessary to give you the access to the bare ground so you can actually plant your trees. So I was out and about last weekend and drove by some slash piles that were arguably bigger than my house.

So thinking about some of those motivations, are there a certain way that you should construct piles in terms of like their size or the location? So you're right. Piles come in all different kinds of sizes, and I think that there's there's a broad range so we can think about big piles. Those are usually the landing piles.

So a landing is a place where the forestry equipment operates, and that might be a place where yarders are working to pull logs back or where there's where there's operations happening with cable yarding or something of that nature. Or something that's happening to move entire trees back to a location where they're processed into logs.

So that's going to result in a lot of that slash being accumulated in one particular area, or maybe a smaller number of particular areas. So those landing piles can become quite large and they're just places where as that material is produced, it's piled and off to the side so that the equipment can continue to harvest and operate.

Um, so that's the really big piles, right? Um, then there's a variety of different sizes of piles that can occur either at smaller landings where you don't have the space for great big piles, or they might be distributed piles throughout a stand. So I've seen piles that are as little as maybe three feet in diameter and a couple feet tall.

Just scattered all over the place. That's usually hand piled slash. Um, I've seen hand piled slash in thicker operations. So operations in thicker forests where the slash might get piled as much as maybe six or seven feet tall. And then, like you say, there's the bigger piles that typically occur associated with landings.

There can also be pretty large piles that occur distributed if an operation goes through and does like a thinning operation and then leaves the pile distributed, but then they come back in with another machine that has a grapple arm and they can pick it up and pile it in locations. And those piles can get pretty big as well.

So the, the actual structure of those it's pretty important if you want them to burn efficiently to make sure that they're piled kind of as tall as you reasonably can and to have the sides relatively straight up and down. That would be kind of the ideal pile would be to have like if you were looking at the pile from the side, it would look like almost like a round barn, right?

So you'd have the sides being pretty straight that way when it's ignited, that heat can move up through the pile. And, and it really helps make sure that the pile burns well, like all of the fuel actually gets consumed. If a pile looks more like a pyramid and is really slopey on the sides, it's likely that the middle of the pile will burn, but it's that maybe the parts around the outside won't burn.

So that's kind of a shape component to it. Um, should we also talk about where to put them? Yeah, yeah, I think that that's really important as well. So when we're thinking about pile locations, um, obviously when you go to burn those piles after they're produced, the heat has to go someplace. And typically heat is going to heat the air surrounding that pile, that heated air wants to rise, right?

So the stuff that's above the piles, which is typically your remaining trees, right? Those remaining trees where the branches kind of lean out over or close to those piles would be susceptible to all of that heat. So to the extent you can, you want to locate your piles so that they're in somewhat of an opening and away from those trees and the, and the bigger the pile, the more distance you need away from those trees, right?

Because not only is the pile going to be bigger, but the amount of heat that it produces is going to be increased. And so the radiant energy that goes off in all directions from that burning pile is going to reach out farther. So you want to have a good size space in there in order to allow that heat to dissipate so it doesn't damage the trees.

Not only do you want to think about what's above the pile, the trees, but it also could be power lines or other things that could be aerial like that. You also want to think about what's underneath the piles. So, if I build my pile right on top of a great, big, old, tough, half rotten stump or something of that nature, not only will the pile burn, but that stump will also burn.

And that stump won't burn efficiently, it will just continue to burn, and that fire will Over time have to work its way down through the partially rotten roots and things like that, that stump could burn out, you know, pile could be completely out, but the stump could continue burning for months and maybe even burn completely over the winter and then be a fire risk the following summer when things start to dry out.

So really thinking about not placing the stumps on big old stumps. That's a, that's a good feature there. And then just in general, if you can place your stumps in an area, that's is it's kind of a clean area, relatively devoid of vegetation and of other slash, that's going to give you the best ability to burn that pile without that pile being able to spread and have that fire move away from where you wanted your pile into the neighboring whatever is left on the forest floor type of fuels.

So having a clean area there, um, sometimes you can clean that area in advance. Other times you just want to make sure that you come in afterwards before you burn the pile and create a bit of a fire line around it, maybe two or three feet around that to just help keep that from spreading. So you mentioned a distance from residual trees, as well as avoiding some of those big rotten stumps, but are there any other considerations that folks should be aware of?

You alluded to one a little bit earlier about the pine beetle. Yeah. So when you think about creating all of this fresh slash across the forest floor, um, insects are out there that are, you know, they've been programmed over many millennia to really be tuned in to where is their dying weak tree matter that they can infest.

So the, the creation of slash almost invariably attracts some type of bark beetle or, or boring beetle that's going to bore into the woods. And so to an extent, you know, it's boring into stuff that's already been cut. It's already been killed. So who cares? The problem is if that population of beetles builds up.

And then comes out of that material, finds it no longer really suitable to reinfest, and then it wants to go someplace else, and it doesn't find slash. In some cases, they can go elsewhere and invade living trees, and then it can become problematic. In the portion of the state where I work, the drier portion, that's usually an issue with pine, and our pines are very susceptible to the Ips beetle.

Ips is IPS, that's the genus. There's two species that are really common in the area, and then we're also getting some that are moving in from adjacent states. So there's really three species that are commonly around now. Um, those Ips beetles, the pine engraver beetles, are very attracted to that recently killed slash.

They like to have material to like bore into that's between three inches in diameter and eight inches in diameter. So that's kind of the range that they prefer And if they can find that they can successfully the females can successfully burrow in there lay lots of eggs and one of the kind of unique features about these Ips beetles is that rather than producing one generation like per year they can produce many cases, three generations and sometimes four generations per year.

So that means that they can build up their populations really quickly. So they invade the slash, that's not so much the problem. They're just helping break down the slash. But then they come out of the slash and they want to go someplace else. So they look for other stuff that's that same diameter range, three inches to eight inches.

So they're going to go find your younger Ponderosa Pine or Lodgepole Pine or Jeffrey Pine and invade that. Um, and then once they've killed that and come back out, they're looking for more. And if they don't find more in that range down low, where do they go? Well, they're going to go to the tops of your big, valuable trees.

So that can be really problematic. And so we really have to be careful when we're doing these thinning operations to manage that slash. Um, there's a great publication by Oregon Department of Forestry on Ips beetles that gives you some advice around that. The challenge with the Ips beetle is that because of that ability to produce many, many generations per year, it can really build those big populations quickly.

So stuff that's harvested in the fall between about October and December. They're not, the beetles aren't really active at that time. And so if they get into it, that you can leave that material sitting and there'll be enough time over the winter that it can dry down in our drier east side forest, um, that that material won't really be able to carry out a life cycle.

For those Ips beetles, even if they get in it in the fall, they won't really be able to be successful in that as long as it can dry down, right? Um, if you're harvesting like from January on, then you really need to be thinking about how you manage those Ips beetles. So if you were harvesting all the time, they would just be constantly finding slash and everything would be fine.

But in most cases, you're not harvesting all the time. Continually harvesting with any one stand and so when you pile that material or just leave it scattered, it's going to become that place where they they build up. So there you want to pile that material and then either burn it relatively promptly within a couple of months of when it's produced.

Or you need to build a big enough pile that the outer material becomes the stuff that's initially infested, and the inner material is a little too wet, and so it dries down a little bit so that the first generation comes out, and instead of going elsewhere, they just go deeper into the pile and then the second generation comes up and they go deeper into the pile, right?

And so that contains them within the pile. So you need a fairly good size pile I usually recommend that those piles are you know at least eight feet and probably eight feet tall and probably 15 feet in diameter as kind of a minimum to keep the bark beetles in there, and I like them a little bit bigger.

So I often recommend that people just do landing piles on these kinds of things where they have the pine, um, because that really will pull that material back out. You can build those great big piles and it really helps hold the beetles in that. But then the key is that you need to burn those within a reasonable amount of time.

So, cause you can't count, they're going to keep the bugs in them forever. So I always like to think about like, for the most part, if we do our thinning operations or fuel reduction operations in the spring or summer. The ideal is to burn them yet that fall so that they don't even have an overwinter time though and that usually is really successful.

So fall burning is kind of my preference and get them taken care of as quick as possible. So, speaking of burning, why don't we dive into that, uh, why don't you walk us through the process of burning a slash pile? Yeah, so, as I mentioned, you, you want to time the burning, one, so that you can manage your insect issues, and that's going to depend on your species.

So, with the pine slash in places that have Ips beetles, that's where it's most, um, an issue to make sure that you really get those burned in a timely manner, right? I really find around the state that most other areas, yes, you'll get some beetles in these piles, but it's usually not as big of a deal. So you have a little more latitude.

So most folks let the piles dry down or season over the course of a summer and then burn them in the fall. And the idea with fall burning is that you can wait until the piles um, one, they've gotten partially dry, but you want to wait until you've started to get some rainfall or ideally some snowfall, so that when you burn the piles, any embers that fly off those piles and land in the adjacent forest area won't find receptive fuels, they're going to be too wet, and so that can be a really key issue there, is to capture those when the surrounding area is moist, but you want to keep the pile relatively dry.

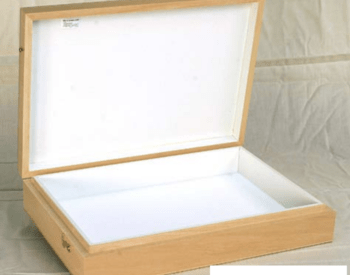

And we do that through proper pile construction. So we talked about building them tall. The other thing it can be really key is to cover the pile, at least part of the pile. So you've got a relatively dry area to get that ignition going. And so if we want to go back to like thinking about Piling for good combustion.

You build them tall, but like build them up partway, make sure that like the middle part of it at the base has some really good fine material in there. If you've got a combination of conifer material with all those needles, if you can get some of that down in the base of that to be the area that can be ignited and you know, you can still get to it with some ignition tool, right.

Then build your pile up maybe halfway, put a layer of polyethylene plastic in there, cover about a 10 by 10 square or bigger if you want, but a 10 by 10 square usually works pretty good. Um, and then continue to pile on top of that and keep it going high up. And if you like finish off, if you're in an area that also has hardwoods, you know, they're always kind of wispy and bendy.

And so piling those on top really helps kind of clamp that plastic down and kind of cap it off. Right. That's going to keep that mass of relatively fine materials with the needles and stuff in it covered and it's going to get dry and that's going to be a great area later when you come back in when everything else is wet around it and even the top of the pile is going to be wet, but you can get that ignite within that.

It'll just burn right through the plastic and then it takes off really quickly. And because it's there in the center or close to the center of that, it makes a heat area, hot area, and it starts a chimney effect that just rushes up through that pile. It dries the wood as it goes and makes for very clean burning.

So that can be a really good way to do that. But again, that's, that's ideally done in the fall. Um, the idea then is that the pile can sit there, and sometimes, you know, a bigger pile might take a week or two to really consume. Um, but it can take even longer sometimes. We know in some cases we'll see like those stumps burn for a month or more, or sometimes multiple months, right?

So if you do winter burning, you have the whole winter wet, cold, maybe even snowy season in there to help prevent that ongoing combustion from moving outside the radius of your pile. So that's really an important technique there. I imagine, too, that if you burn the piles in the fall, then the site would be ready for planting in the next, uh, late winter, early spring.

Yep, exactly. That's that's a really good point. You can also burn in the spring and sometimes like if you're work doing winter operations and you just don't have the time to like within the schedule to get things dry enough to burn. So some, sometimes you'll see spring burning operations that gets a little more dicey because if that continues to smolder.

It's now as time progresses it's not moving into the weather season is moving into the dryer season so that just gives you more potential. But that might be something that, you know, gets a dry wind on it and, and builds up some heat in there and then can spread beyond where you want it. So I have my piles built, uh, we're out of fire season.

We've got plenty of rain or snow. I'm ready to go burn them. Who do I need to talk to, or is there a notification or a permit that I need before I can just go out there and start lighting them off? Yeah, so you asked two good questions. Who do you need to talk to and are there permits? And the answer to both of those is, yeah, you should be talking to somebody and there's definitely permits you need to have.

So I always recommend that folks talk to their, their Oregon Department of Forestry Stewardship Forester. Those folks are in the know around all things relative to burning and smoke, and so those are really good starting points to know exactly what you need to do in your area. The truth is that the rules for how you get your permissions, particularly on the smoke side, of the piles, the smoke produced by the burning, uh, they vary across the state and they vary depending on where you are, like relative to cities and things of that nature.

And sometimes they can even vary by county. So it's just really a good idea. It's like, even if you're used to burning someplace else, and now you're going to burn in a different area of the state, contact the stewardship forester there and have them walk you through the process. So that's, that's like the basic step.

Start there, right? Then, when you're burning slash, that's considered a forestry activity if it's on ODF protected ground, which is most of the private forest land in the state. There you need to file your notification. You probably already had a notification for the forestry operation, but you need to make sure that your notification includes the burning of those piles.

And then because you're burning, you have to get a permit for burning. And interestingly enough, it's not called a permit for burning. It's called the permit for power driven machinery. Right. It's a PDM, so it's just lumps everything that could produce fire into one bucket. And the power driven machinery is like prone for making sparks and stuff.

And so the same permit that you use for power driven machinery is the one that applies for fire. And so you need to have that as well. So the notification of operation, the permit for power driven machinery to get your basically your fire permit, right? And then on top of that, you need to to register your burn through the Oregon Department of Forestry smoke management system.

And so there's a form that you can download from the Oregon Department of Forestry website. You fill out the form there with how many acres you're burning. And it doesn't mean that you're like physically burning every bit of those acres, but you're burning the slash that was produced on those acres.

And there's, there's, you can check box in there. Am I burning it in piles or the whole bunch of piles all distributed? Are they at the landing? Am I just like leaving it distributed and then burning it as a broadcast or an understory burn? Right. So there's all kinds of options in there. So you need to file your notification.

In the Western Oregon, you pay a fee associated with those number of acres, um, to help them fund the smoke management system. And then that information feeds into the people who do basically the smoke management weather forecasting. Because what you have to do is make sure that on the day that you're actually burning, that you can have permission to make the smoke, right?

And remember that you're probably not the only one in your area that wants to burn piles on that day. There's lots of people that want to burn piles. And it may be that not everybody gets to burn on that particular day. It's going to depend on the atmospheric stability, a stable atmosphere holds the smoke low.

And it makes for those days when we have the really smoky atmosphere don't level where we breathe, right? And unstable atmosphere means that that smoke's going to rise and really dissipate well, um, but also make for more extreme fire behavior, right? So, so the, the smoke management forecasters will be able to really determine whether that's a day when people can burn or not.

And your registration goes in and allows them to determine who gets to burn on those days based on how many piles they have, how much did they cover, where are they, what are the forecasts say for stability, the atmosphere, which way the wind's blowing, what's downwind of where that smoke's going to go if there's a city there.

It's really sensitive to that smoke, a smoke sensitive receptor area. And that's going to have an impact on how much smoke you can produce and basically how much tonnage you can burn of the piles. So do they let you know when you can burn or how many piles you can burn on a given day, or do you have to just call and figure out if the weather conditions are conducive of that?

So it's a combination and it really kind of depends on where you are. So in many places you do call and so you submit your registration. I always do it talking with my stewardship Forester, right? And for a small woodland owner who may have a really like just a couple of piles to burn, they may say, yeah, when you get ready to burn, just let us know a couple of days in advance and it's probably not going to be a problem, right?

If it's a big industrial burn where there might be hundreds of piles with many, many tons of stuff being produced, they're, they're going to get scheduled into that system and they may be told they can only burn a portion of those on any particular day, right?

Um, there are other parts of the state, so Union County is one where they have kind of automated that process, and so anybody that's producing smoke, whether it's forest related or otherwise, right, you call in and and there's like a a phone system where you like press one for this and press two for this, right?

And it walks you right through it and it will actually take you through the whole system there And tell you whether you can burn on that day. So that's a pretty cool system. There's a couple other counties that I think have something like that um, so central oregon like the Deschutes area I think has a pretty distinct way that they manage that kind of stuff.

I think Jefferson county may have something of that nature. But for the most part, again, it's really good to stay in touch with your stewardship forester. And then they'll tell you how to best to interact with your smoke management forecasters. So let's say that I have my permits, I have all my notifications in and I'm ready to go light some piles.

Is there anything specific in terms of firefighting equipment or tools that I might need? Or can I just walk out there with the jerry can and a box of matches? I think we should start on what to wear, right? So, um, a lot of us know when we're out in the woods, we wear our synthetic fleece stuff that keeps us all warm and toesy.

We've got our fancy synthetic, you know, nylon or polyester long johns on and things like that. We might have our great outdoorsy pants that are made out of nylon. That's probably not the best stuff for burning piles because it will melt and it will melt into your skin. If you get an ember on you, that's a bad deal.

Right? So old fashioned cotton or wool clothing would be ideal. If you're a firefighter and you have nomex or some other kind of flame resistant clothing, that's cool. That's really good to wear. Um, but for a lot of us just out there burning piles, we know we're going to get kind of greasy and stuff carrying the drip torch or other fuel source around.

And so just wearing cotton that we can take home and wash is a good thing. The cotton, it's going to be damp that time of year for burning in the fall. And it makes for a pretty good barrier against that heat. So what you wear is important. Wear good boots. If you think you're going to be climbing up on the piles to like be able to get down in them and get your ignition going.

Um, I recommend wearing the cork boots, the ones with the little spikes on them. Right. So make sure that you've got some safe way to get into that area. Um, I, I burn a lot of Northeast Oregon and I ended up having to wear snow shoes. To get into my sites, right? And so be able to actually get across the snow because all of a sudden, once it snows, instead of having two inches of snow, which would be ideal, I might have two feet, right?

And so being able to get in there is important, right? Then we, we need to have something to ignite the piles with, right? So a lot of us have done firefighting stuff. We love our drip torches. And so we have a mixture of diesel fuel and gasoline that goes into the drip torches. And then that allows us to light that tool, dribble some of that flaming fluid down into the base.

And if we can get into those fine materials underneath that tarp, that plastic covered area, that works really nicely for, for getting those ignited. So, so there's ignition source, right? Um, there's other sources too. Sometimes if I have kind of a wet pile, you've probably all seen these weed burners. that are like a metal tube with a flame thrower type of thing at the end, not really a flame thrower, but a, uh, a burner type unit at the end.

And then it connects to a relatively long hose on a propane tank, right? So you can light that, push one of those into the pile and just hold it there for several minutes while you're really getting that, that wood heated it up in there. And that can help, particularly if you don't have enough fine material in there to really get a heat source in there to get things going.

Once you've got it going, if you've got a leaf blower that you can use to continue to put some air into the base of that pile, that can be really useful. You might want to think about like retrofitting the plastic tube that comes out of most of these leaf blowers with at least a section on the end that's metal, so it's more resistant to heat.

Um, I've seen a number of melted leaf blowers, but but it really works to get that extra, um, air into the pile. Um, there's, there's a variety of other type of ignition devices. Some people will even just use like the wax log thing, like you use for lighting a fireplace fire, you know, there's lots of things if you're just doing a couple of piles at the home, you can even roll up newspaper.

You can roll up newspaper and put wax on it, like just. Whatever you use to normally start fires. If you've got a pile with some dry stuff in the middle, because you tarped it well with your, with your plastic, that you probably can get that going without anything fancy.

And then if you're burning in the fall, when you know, you've got, you know, like if I've got two inches of snow on the ground, I'm probably not going to worry about any other equipment at that point. Right. I'm just going to get it burning. I know that if I have embers, it's going to fly away from that, it's going to fall in the snow and not be an issue.

Um, and if it did land anyplace else, there wasn't much I could do about it anyway, right? And so I really want to just be thoughtful of that. If I'm doing a, a burn at a time of the year when there's the potential for it to actually light stuff on fire, then I do want to have some equipment on site. So I'd want to have a water source.

So usually that's going to be some sort of portable tank with, I would say at least 250 or 300 gallons of water right and some type of pump and some hose so that if something ignites near that pile you can manage that right? And so if you're if you're so hopefully you're not burning on a terribly windy day you want a little bit of wind in order to like get things going here. But you don't want a really windy day that's going to carry those embers from the pile along direction. So, if you're burning kind of on a normal burning day, um, you know a few hundred gallons of water in a tank either like A portable one in the back of a pickup truck with a pump in there and a couple hundred foot sections of hose and a nozzle.

That's probably what you can like kind of the minimum that you can get by with for for tending those those piles as you're working on them, right? And you can spend a lot of money on a portable tank or you can get a relatively inexpensive water pump and you can get one of the IBC, the bulk containers, like they come in the cage or the plastic container that comes in a little cage.

Those are usually available for relatively inexpensive. They hold either 250 or 330 gallons of water, depending on what size you get. And so they can be a really great tool and lots of people on ranches and farms and forestry homesteads have those already. So you can just retrofit that, make sure you got a way to plumb it into your pump, and then a way to adapt your pump into, I would, I would get at least a section of at least one inch hose, um, so that you can carry some volume if you need it.

Um, but that's, you know, that's kind of the minimum that I would have for tools. If you're, you know, you can think about this broader too. If you've got equipment and you have a dozer, um, and you want to have that on hand, um, but I would say that if you're feeling like you need a dozer on hand in order to do your burning, you've probably picked a poor day for it.

So if folks don't have access to some of these resources or equipment or maybe don't feel comfortable doing the burning themselves, are there any resources or folks that could contact for assistance? Yeah, and you can talk with your Oregon Department of Forestry Stewardship Forester and they can help point you to people who do burning for other people on a contract basis. But I would start with just like if you're hiring somebody to come do the fuel reduction or the thinning operation or logging on your operation your property talk with them Because chances are pretty good that they already do pile burning, right?

So most of those contractors will do some of that. And so you might want to see if you can just work that directly into the contract that you have with them It won't work for everybody all the time, but that's a good starting point. Then, like I say, you can talk with your stewardship forester because they probably know who else in the area does that.

Um, often the same crews that do reforestation will also do pile burning and hand pile, right? And so different times of the year, they're doing different things. And so those can be really accomplished burners who can come out and do that work for you if you, if you don't have the ability to do it yourself.

And then what about after a pile's burned, uh, is there anything that needs to be done in terms of cleanup or getting ready for, um, planting or rehab of a site, you know, thinking one week after it's burned to even months after it's burned? So I would start the day after the burn and make sure you're back out there, just checking every one of your piles, making, just getting a sense for how much of it's burned down, you might be looking and seeing whether you got good consumption or whether you have kind of a ring of unburned material around the edges.

We often call it a crow's nest. Um, so that's where if you have a tractor with a bucket or something of that nature, like if you want to push that material back to the center of the pile area, the burn area, you can get a lot better consumption. So that's a pretty common practice for small woodland owners who might have a tractor with a bucket.

But also you want to be there on hand just to make sure that the fire is staying in the piles and has not escaped and be burning someplace else. So that follow up patrol. The, the days following are really important, right? And so, when I do burning, I definitely am there the day after. I'm usually there the second day after, just watching them again, just checking on that kind of stuff.

And then, depending on the weather, like if I get a big rain period, maybe I don't have to check it again right away, but as soon as it starts drying out again, I'm going to be back out there checking and I'm going to continue that patrol until I really am confident that, that my piles are burned out. And I can't be confident my piles are burned out unless I get out of my truck, walk to my pile with my forestry hand tool.

I like my rogue hoe and I dig around in all the places where I think there might be heat and then I take my ungloved hand very carefully the back of my hand and kind of feel around there just above the burner, the ash layer to make sure that I'm getting the heat out of that, right?

And so I want to just continue to check that and be like thorough in the process. And what you're going to find in that is that, you know, places where The pile was really clean and well stacked that burns up really completely over the period of a few days. Were you, like if it was a dozer pile where the dozer was pushing material into it, even if they're pushing with a, with a brush blade, the forked blade, that's a better option than just a straight blade.

But even with that you still get some you know, you get rocks pushed in, you get clumps of dirt and sod pushed in. Those are the things that will hold the heat and smolder for really long time, sometimes weeks or even months. Right. And so there you would want, if you want to get those out, you, you have to kind of disperse that material, re expose it, get it to burn or put it out with some water.

And so you really have to pay attention to them. And so yes, keep, keep an eye on them. And then the other thing I would say is that even if you're feeling pretty good about those piles. Anytime that you have an event that, you know, gets the wind up, particularly if it's a dry wind, that's a, you want to get out there and just make sure that nothing has come back to life.

Cause sometimes the fire can kind of hide from you, but those dry windy days can, can really bring back into a flaming condition those things that you might think were out, right? So, western Oregon, those would be east wind days. So, days when there's wind blowing from the east to the west. So those, those happen when you get like higher pressure systems that sit basically at the top of the mountains.

It blows air downhill. As it comes downhill, it compresses and gets warmer. So we get those dry, downhill, windy days. That's what the 2020 fires were. Um, and so those are really days when you want to be watching those piles, even if you thought you had them out. So if you can get back out and check them, that's really important.

Eastern Oregon. Um, that could be a west wind day coming downhill on the eastern flank of the Cascades, or really, eastern Oregon is typically dry enough. It could just be a windy day from any direction, and so just keep an eye on those piles and kind of make sure that they're out. There are some cool, new, newish devices where you can like actually do an infrared sensing to sense if there's heat in the piles.

And so those are being something that's more commonly used by pile burners, foresters, firefighters, things of that nature. Because they can help you determine if there's heat in those piles, even if it's not readily apparent to eye or even by skin sensor, so. And what about, uh, let's say months after a pile's been burned, is there anything to be aware of or to watch out for thinking specifically about things like invasive species?

Yeah. So, so, you know, I think that follow up to piles really depends on what your objectives are. If you've got a spot where, you know, like, you know, we're doing a series of operations in here and every year, you know, for the next few years, we're going to be bringing stuff back to this location. And we're going to reuse this landing site.

We're going to build another pile here. Um, I wouldn't spend a bunch of time rehabbing that site probably, right? If I have a site that like, no, we're probably not going to do anything here again for 10 or 15 or 20 years, right? Um, that would, would suggest it's a, it's a wise investment of your time to clean it up.

Right. So that can involve a couple of things. So if it's near a landing other people might drive in and get close to there. I would want that landing to be relatively clean so that it can't carry fire. And let's just think about what's happens at landings. You've all been on landings at the end of the road out there on the forested property and people go there who aren't you, right?

And so it's the, the, the people who come in and they may be trespassing, or it may be actually like not marked in a way that prevents them from coming in there, but they invariably end up building their campfire at that land. Leaving it unattended and so if it can spread it will so having a clean landing or that material isn't there to be something that can carry fire.

That's a good, good first step, right? Um, beyond that, um, if there's areas off the landing where you want to make sure that you don't have invasive species in there. Burning, burning that material in the fall, then gives you the option to come in during the wet or snowy period, and to seed that with like a native seed mix, um, and allow that to, to regenerate to some plants that can help compete with the invasive species that might come in later, right?

So if you can get that grass established or whatever, you know, those native shrub species and things reestablished on that site relatively quickly, you're much less likely to have that big round patch of thistle or other thing that might come in there, right? And so really getting those established relatively quickly.

So that suggests some forethought, right? If you know, you're going to have a number of piles of X diameter, you can calculate how much area that is, and then make sure that you've ordered in advance to have a native seed mix that you can have in there to get it out there and get it on the, on the ground and.

I like, like northeast Oregon, I like to get that seed mix on to burn the pile in the fall and then come back in after that when it's out and, you know, I'll know at that point because over there there's snow, right? And so if the snow has stopped melting off my site, I know it's cool. And at that point, I can come in and just seed right over the snow and that, that, that seed sits there in the snow.

It has time to soak up some moisture and then in the spring, as the snow melts off, it just settles right down into that fluffy ash and off it goes and it just regenerates very nicely. So that can really help reduce particularly the thistles and, and Mullen and other, other species that are really invasive on those sites.

So I know that we're focusing on piling slash, um, but are there are alternatives, uh, or what other options might folks have if they want to address some of the residuals following a treatment? Yes, there are options. So let's think about some like some different categories, but also some like different levels of the amount of slash, right?

So I always tell folks that if there's like you're coming in and you're doing a thinning operation in small regenerating trees, just because you know, you've got too many of them. And there's a few here and a few there. Like you don't need to pile that stuff, right? So you can cut that off, knock a few of the limbs off the side, get it to lay down on the ground and it'll dry out and just lays there on the ground, right?

And if you're in Western Oregon, it actually kind of decays away relatively quickly. If you're in Eastern Oregon, it's going to lay there for quite a while, maybe decades, right? But it's not really a fire hazard because there's not enough of it to really contribute substantially to a fire, right? So we call that lop and scatter.

If it starts to be to the point where, like, you're lop and scatter and there's stuff every place, that's probably suggesting you need to pile that, right? So, so there is, like, there's that differentiation where maybe sometimes you don't need to pile if it's just a really a small amount. There's also, you know, I would say, too, that when you're piling, the stuff that really burns well in the pile is the smaller material, right?

If you've got bigger material that Isn't pine, right? So the stuff that's not going to attract the Ips beetle, some of that could be set off to the side and maybe you use it for firewood. It's like anything that you can use for firewood use for firewood is less smoke we have to put in the air in that, in that less controlled manner, right?

So you may as well at least get the heat out of it, right? There's other places, particularly if you're at the bottom end of a sloped unit, you're down near the riparian area. Maybe you want to leave some of that bigger material kind of stacked and let it be an area that wildlife use. I wouldn't put a whole lot. But having a few of those can be perfectly acceptable.

So, so that's another option. Then you might start thinking, well, maybe we're like bringing all the material back to the landing and I could get a chipper to the landing and I could just chip all this material, right? So then it's like, do I chip it and leave it on site? Well, it takes a really long time for chips to break down to naturally decay.

So maybe that's not a good idea because if you do catch that stuff on fire, it just sits there smolders for a long time. And that can be hazardous if you get a wind event, right? And it's also actually kind of hazardous to the soil because it makes a lot of long term heat that goes down into the soil and can essentially kill off a lot of the microorganisms that are so important there, right?

So, so chipping one option, but maybe you want to think about where can you take those chips? Can you use them elsewhere? Can you do something with that? Um, if you have really flat ground, maybe you can do some inwoods chipping and kind of distribute that stuff I would avoid making like really deep chip layers that can have some implications for soil nutrition. But you know a little bit here and there scattered around that's going to be just fine. And then more commonly with some of our fuels reduction practices, we use something called a masticator.

So it can, it's a rotating either drum or kind of a blade type device that sits either on an excavator or a tracked vehicle that kind of looks like a skid steer. And, and those can drive through the stands and just kind of grind up stuff that's in front of them and leave it distributed. So mastication, you'll sometimes hear that called forest grinding or even mowing.

Grinding up that material and leaving it behind. Again, I really think it's important to think about what's coming next because if your thought is that in the future, you're going to do prescribed fire in a broadcast manner across those sites, having a bunch of masticated material or chip material on that site is going to complicate your ability to do a successful burn there, and it could even be counterproductive to your soil health.

Whereas if you brought it back and piled, you can get, you can really control where that heat is going to be and where you're going to come back in later and need to do your rehab. So really think about those, those different options there. Were you thinking of any other methods? So we got piling, we got leaving it lop and scatter, we got chipping.

And then we got, um, doing the mastication. And I guess maybe the other one is you could just decide that maybe it's so like, I know there's places in Scandinavia where they're really good at bundling the slash and moving it off site. Um, they actually have baler type machines that bail it kind of like a hay bale, it comes out kind of these round bundles.

Um, and then they take it down to a biomass plant and actually use it for fuel to generate heat and in those plants, they can do it very efficiently with very little smoke residual that comes out because they can capture that in the manufacturing process. Not to get too into the weeds, but the only other one I was thinking of would be biochar as well.

Oh, yeah, so particularly if you're a smaller operator and you wanted to experiment with producing some biochar on the site, that just means that you're probably going to have either some really specific piling methods and some, like, some particular ways that you extinguish the fire at a certain stage, or you might actually have a container that you burn that material in.

What I would just suggest in there is that biochar operations may actually have different regulatory requirements than pile burying, depending on how they're done. So again, check around a little bit. You probably wouldn't get in trouble for it, but Department of environmental quality regulates that kind of burning.

And there may be additional permits or different permits that are required for doing that material. The idea behind biochar is that you, you kind of take this woody material. You, you, you burn off the stuff that will readily turn to gas and burn and make the flames that you see in the air. Right. And you leave the relatively pure carbon, mostly unconsumed.

And then if you can incorporate that back into the soil, um, historically, that biochar, um, if it was produced naturally, we call it pyrochar, but it's just basically charcoal. And so if you, if that's incorporated back into the soil, it's a really important way that the soils hold moisture. And it also helps hold the nutrients because the nutrients can attach to that.

And then later on when plant roots or mycorrhizal fungi come in contact with that, they can relatively easily access those nutrients. So that can be. important process there. Um, I often find though that pyrochar or, excuse me, that biochar in the forest is a little bit complicated. But if you're, like say, if you're a small woodland owner and you've got the option to do that for relatively small batches, um, that can be really effective.

All right. Well, we are nearing the end here, but I want to make sure we don't miss anything. Uh, John, do you have any parting thoughts on slash, piling, burning, or anything else you'd like to share? So, yeah, so let's just remember that when we burn, we're releasing heat and smoke into the atmosphere, and we should be really, before we make the decision to pile and burn, let's think about what's next to where those piles are, right?

So if you know that your neighbor just over the fence has asthma, and that, you know, the prevailing winds in your area are almost certainly going to push smoke at some point during the burning operation down there and cause problems for them, maybe that Kind of pushes you or is you to think about some non smoke producing way that, that you, that you take care of that slash.

So maybe that suggests that you masticate or that you chip or that you haul it off site or that you do pyrochar or excuse me, that biochar, where you maybe have a little bit more control over the burning process, right? So maybe those, those options, there are some places where, you know, if you really get kind of looking into it, you just can't burn.

You're too close to the smoke sensitive receptor areas. The towns are areas where there may be are elder care facilities or something of that nature where people are really sensitive to smoke. And so sometimes you just can't get that. And it doesn't make any sense to spend a lot of money building piles if you can't actually burn those piles, right?

So make sure those carry through. And then again, if you do build piles. Make sure you burn them because if you don't, you've just left a whole lot of fuel on the site and sooner or later the grass and the shrubs are going to grow back in around them. And now any fire that carries in there, not only is going to burn, you know, in that relatively low intensity manner through the grass and shrubby stuff, but it's going to hit those piles and make for really hot spots and a lot of embers within that.

So that can really lead to a much bigger, more intense fire. Um, be thoughtful of where those piles are. And like I said before, if they're in areas where somebody else can catch them on fire, then you really want to be thinking about like, what do you want to do for follow up manage to make sure that those things are not being reignited.

Or if you, like, if you're in a forest where you've done a bunch of harvesting, remember that our roads, like they usually go into the forest, hit the landing, and then you got to come out the same way, right? So if I've got a dozen piles along my forest road, and they're right next to my road, which they often are, um, when I'm burning those, I probably want to drive all the way to the end of the road, light that pile, and then work my way out.

If I do it the opposite way. I might get stuck in there, or I might melt the mirrors off my truck on the way back up, right? So, let's like think about how you stage that to safely burn those out, right? And then, like, also thinking with that, I was just in a really interesting higher elevation area in the Blue Mountains, where they've done some really great hand thinning and hand piling in a very, very dense, um, mixed species stand, mostly taking out lodgepole pine.

Um, there were piles that there were so many of these hand piles that they were almost touching each other. It was that dense, right? But there's still trees that they want to retain in the overstory.

So there was, there was like no possible way that they could just come in and light all of those piles and have that not kill the over story trees, right? So what they did, this is really good thinking, right? They waited for a cold. It was below zero. They had like a little bit of snow on the ground. So that's going to help mitigate the overall heat.

And then the contractor who was working on that came through and he had his crew light every fourth pile. They just kind of stripped it through. They let every fourth pile. Let those burn down for like half a day, came through and lit the next group of every fourth pile, right? Came back the next day, did the next group of every fourth pile, and then came through and did the last of the fourth pile, right?

So it took four passes through, burning a fourth of those each time, so that they had a fourth of the heat each time. And when I checked on that, like a week after they burned, they actually had pretty minimal amounts of scorch in, uh, in the crowns of those trees. Um, it was masterfully done. And so you really have to think about the logistics of how you manage that when you're doing more of that burning.

And then finally, remember that heat goes up, but he also goes down, right? And so when you're burning in those piles, the bigger the pile, the more time it's going to take for that to burn down and the more of that heat is going to transmit down into the soil under the soil environment underneath that pile.

So not only will you have the ashy environment there, but you've, you've killed off the microorganisms there in that area underneath that pile and the bigger the pile, the longer it takes for that to reestablish. They will reestablish, but it takes a longer time, the bigger the pile is. So while the big pile may be kind of ideal for keeping the Ips beetles in the pot, that big pile has the downside of creating a longer, um, impact, a longer lasting impact on the soil underneath.

So there's a very distinct dynamic there. So you really kind of want to weigh the pros and cons of each of these techniques as you, as you initiate your prescribed fire burning exercises, activities.

Those are all really, really great points. And I think a great way to wrap this up here. So if done correctly, piling and burning slash can be an effective way to reduce potential fuel for wildfire and prepare a harvested area for reforestation. John, thank you so much for sharing your expertise with us today.

If any questions came up while you were listening, or if you'd like to learn more, please drop us a comment or send us a message on our website. All right, John, before we wrap up here, we conclude each episode with what we call our lightning round.

We'll start with the first one. What is your favorite tree? So I want to ask you a question. Do you want my favorite tree species? My exact one favorite tree. Uh, why don't we just do both? Do both? Okay. So I like to clamber around in the mountains, and so I'm really enamored with whitebark pine, which is the crazy twisty pines that grow way up at higher elevation.

So my favorite tree species is whitebark pine, but my favorite individual tree is a very ancient, like 1,500, maybe 2,000 year old limber pine, which looks a lot like whitebark pine that sits way up in the, in the Wallowa mountains, way up at high altitude. And it is the craziest thing. It is 11 feet in diameter, like on one side, eight feet on the other side.

And so it's huge in diameter. It's only about 30 feet tall. It just sits up there, it's windswept, and it's just a crazy looking thing. It looks like something out of a, like a science fiction movie on a different planet. It's so cool. So that's my favorite tree. I periodically hike into the mountains for many miles, go sit by it, and I talk to it and ask it to tell me stories.

So far it's been very quiet, but I like to talk to it anyway. How many miles or how many feet of elevation gain did it take you to find this tree? So, so, now that I know where it is, it is a mere 34 mile round trip with about 6,000 feet of elevation change. So just an afternoon stroll. Just an afternoon stroll.

Alright, our second question is, what is the most interesting thing you bring with you in the field? Whether in your cruiser vest, field kit, line bag, etc. Well, I don't know if everybody would consider it interesting, but I have really come to like my little, like laser range finder that has the built in clinometer so I can measure tree heights.

I have a relative, it's not a super fancy one, but you can get these now that, you know, for 300, 400 bucks, you can get the ones that will determine distance to the tree. And then you can get the angle to that. So you can determine the tree height. And since I ended up doing a lot of my forestry work by myself with nobody else there with me, it just really saves a lot of time to be able to, to use that laser range finder with the angle gauge built into it.

I wish I had the privilege to have a laser range finder sometimes when I think back to past experiences in the woods. Yes, exactly. And then lastly, I know we mentioned some already, but what resources would you recommend to our listeners if they're interested in learning more about all things related to slash and prescribed fire, pile burning or other prescribed fire methods?

So go to the Oregon Department of Forestry website. Department of Forestry, and then on their publications, look through their lists, they have a nice publication on Slash Management, read that, they have another one on Ips Beetles, that gives you that, a nice diagram of their life cycle, and like, different things you can do at different times of the year, um, I think that's a really good one just for general reading, I don't think that that particular has the, my recommendation around big piles, but you can kind of see how it fits into that, right?

So that's a really good one there relative to yips beetles and just in general. There's a ton of stuff on there, right? While you're there on that site kind of back out one notch out of publications. And if you kind of look on their page, you'll see a link in there for for burning and smoke management.

That's where you can get the form you need to fill out for your smoke management registration. It's where you can get information on the weather forecast. They do a daily weather forecast update for the four different zones that comprise the forested parts of Oregon. So that's where you can get good information on that.

It'll give you all the details and all the information you need to know there. So that's a really useful one. And then just like in general, there is a really cool publication from the Oregon Forest Resources Institute, OFRI, called Managing Logging Slash Piles in Northwest Oregon. So it's kind of written for that area, which has those higher slash loads.

But, but what it describes in there is really applicable all over the place. And so I would recommend that you can either write to them and ask them to send you a printed copy, or you can just go online and print your own copy for no cost. So really good resource, and again, that's managing logging slash piles in northwest Oregon.

It's available from Oregon Forest Resources Institute. So I think that would be my couple of recommendations is those two resources. Well, John, really great to see you. Thank you again for being here today. I really learned a lot. And hopefully folks will have a different perspective as they see some more smoke in the air or see some small fires on the hillside while they're out and about this fall.

Yeah, thanks, Jake. And yes, as you see that smoke, know that that's responsible for the most part, that's responsible forestry just undertaking that slash management is so important, important for fuels reduction and mitigating the risk of wildfires and making sure that we're managing in a way that doesn't build up big populations of damaging insects.

So good work out there on the land. Yeah, absolutely. Well, this concludes another episode of In the Woods. Thank you all so much for listening. Don't forget to subscribe and we will see you all next time. Bye everyone.

Thank you so much for listening. Show notes with links mentioned on each episode are available on our website @inthewoodspodcast.org. We'd love to hear from you. Visit the Tell Us What You Think tab on our website to leave us a comment, suggest a guest or topic, or ask a question that can be featured in a future episode.

And give us your feedback by filling out our survey. The In the Woods Podcast is produced by Lauren Grand, Jacob Putney, Scott Leavengood, and Stephen Fitzgerald, who are all members of the Oregon State University Forestry and Natural Resources Extension team. Episodes are edited and produced by Kellan Soriano.

Music for In the Woods was composed by Jeffrey Hino, and graphic design was created by Christina Friehauf. We hope you enjoyed the episode and can't wait to talk to you again next time. Until then, what's in your woods?

In this episode, Jacob Putney is joined by John Punches to discuss tips and regulations related to piling, managing and burning slash.