New producers of small ruminants often first learn about pregnancy ketosis the hard way — with a dead dam, fetuses or both. This article explains the causes of pregnancy ketosis (aka toxemia) and more importantly — how to prevent it.

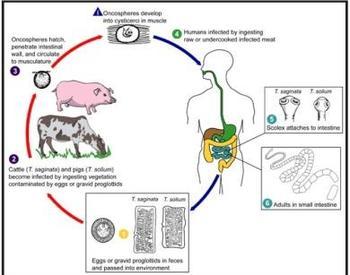

Sheep and goat fetuses add 70% of their final birth weight in the last six to eight weeks of gestation. A singleton increases a dam’s nutritional requirements by 1.5 to 2 times maintenance in the last trimester. Multiple fetuses greatly increase energy demands on their mother: twins require 1.75 to 2.5 times maintenance requirements and triplets demand up to 3 times maintenance. Twins and triplets are common in some breeds of sheep and goats; quadruplets and even more are not uncommon in Boer goats, Finnsheep and Romanov sheep.

Concurrent with a pregnant dam’s increasing nutritional needs, her physical capacity for feed intake is reduced by the rapid abdominal expansion of her pregnant uterus. Without managerial changes, the dam will be unable to ingest the calories needed to support herself and her fetuses, sending her into negative energy balance.

Detecting a drop in blood glucose levels, her body’s regulatory systems will liberate energy from reserves stored as body fat. The release of stored energy will address her low blood glucose issues (remember the Krebs cycle?) but not without side effects: byproducts of fat mobilization called ketone bodies can accumulate to toxic levels and suppress appetite. Without intervention and sometimes despite it, affected does or ewes may spiral downward in a fatal negative energy balance, taking their unborn fetuses with them.

Besides multiple fetuses, health and management factors can predispose a pregnant ewe or doe to ketosis during pregnancy.

For example, if there isn’t enough feeder space, timid individuals may not be able to eat their fair share of the ration. Lameness or other health issues may prevent affected animals from walking to food or standing to eat. Thin does or ewes already lack sufficient nutrients to maintain themselves, let alone grow a fetus or three; they are predisposed to ketosis as pregnancy progresses.

Any issue that causes a late-term pregnant doe or ewe to have reduced feed intake even temporarily — transportation, shearing, inclement weather, etc. — can result in ketosis. This is especially true for overconditioned animals; fat mobilization can cause fatty infiltration of the liver and fatal ketosis after a relatively minor period off feed. Large amounts of intra-abdominal fat in obese sheep and especially goats further limit free space in the abdomen for the rumen to expand into to receive a high-fiber diet.

Signs of pregnancy ketosis (see photo) are initially subtle and include depression, lethargy, poor appetite, dull eyes, low fecal output, changes in behavior and general “slowness.” As the condition progresses, affected animals may manifest tremors, circling, teeth grinding, blindness, wandering, stargazing and incoordination progressing to recumbency, coma and death.

Managers can monitor and/or diagnose individuals for ketosis through the use of urinary ketone detection strips, blood ketone tests and/or checking the breath for a fruity or acetone smell (although not every person can smell this). Early cases that are still eating can be given more energy (molasses, more grain, better quality hay) and two to three ounces of propylene glycol orally every eight to 12 hours until birthing; this substance is converted to energy by ruminants. Detection of the first case of ketosis should motivate a producer to reevaluate the herd’s ration, assess body condition scores of all pregnant animals and make adjustments as needed.

If a pregnant doe or ewe totally stops eating due to ketosis, her outlook declines greatly. Traditional treatments include intravenous dextrose and oral propylene glycol. Recent additions to treatment protocols may include the use of calcium, potassium, sodium bicarbonate, ionophores, flunixin, probiotics and thiamine.

Few of these medications are approved for use in sheep or goats, so they must be used under the guidance of the farm’s veterinarian. Labor induction or a C-section may be warranted as well. The purpose of these actions is to remove the source of energy drain on the dam (i.e., the fetuses), but the fetuses are often sacrificed in the process or already dead.

Prevention of pregnancy ketosis includes giving pregnant does and ewes a more energy-dense ration beginning in the last four to six weeks of pregnancy. This dietary change should begin slowly and increase gradually. Using the results of ultrasound pregnancy tests, individuals can be separated, fed and managed as a group, depending on the number of fetuses they are carrying.

Does and ewes pregnant with twins and triplets will require a more energy-dense diet than those with singletons. Those with singles still need to be monitored, but could grow excessively fat on the higher-energy ration required for twins and triplets. Exercise helps prevent obesity and improves muscle tone. Providing feed, salt, water and housing in separate areas will force animals to move more than they might choose to do voluntarily.

Aim for body condition scores of 3.5 at birthing. If animals are overweight, late pregnancy is not the time to take the extra weight off; keep them eating well and monitor closely because they are at elevated risk for ketosis.

Animals with body condition scores below 3 should be identified and fed to improve body condition before birthing so neonatal vigor, colostrum production and lactation are not compromised. Depending on body condition score and the number of fetuses being carried, individual animals may require one-half to three pounds of energy concentrate per day, often averaging one pound per fetus. Dividing the concentrate into two or three meals per day fed after hay is best for rumen health.

Given the close profit margins achieved by small ruminant producers, it is essential to understand pregnancy ketosis and how to prevent it. Experiencing it once is enough for a lifetime.

Additional reading

- Goat Medicine by Smith and Sherman. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, 2nd. ed. ISBN-13: 978-0-7817-9643-9.

- Sheep and Goat Medicine by Pugh and Baird, 2nd. ed., 2012. Elsevier ISBN 978-1-4377-2353-3.

- Maryland Small Ruminant Page: Pregnancy Toxemia in Ewes and Does

- Merck Veterinary Manual: Pregnancy Toxemia in Ewes and Does