Transcript

Welcome to part 2 of Scheduling Irrigation with a Pressure

Chamber.

I'm Dr. Alexander Levin, a viticulturist

with the Department of Horticulture

and core faculty member of the Oregon Wine Research Institute

at Oregon State University.

Now, before we make an actual measurement,

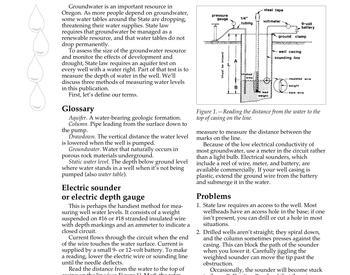

let's take a look at some of the key features of the instrument.

This is the actual chamber, the lid that seals it,

and the compression screw that seals off

the petiole from the outside air.

Over here is the compressed gas tank and its connection

to the chamber.

There are two gauges on the front of the instrument.

One gauge indicates the pressure in the chamber.

And the other gauge indicates the remaining pressure

in the tank.

Here is the main control valve that allows gas

to flow into the chamber and exhausts

the chamber when we're done with the measurement.

The rate valve controls the gas flow rate

into the chamber during pressurization.

The safety valve automatically releases gas

from the pressurized chamber if the chamber pressure

were to ever exceed the safety limits of the instrument.

If you are measuring leaf water potential,

you'll need a regular sandwich bag.

But, if you're measuring stem water potential,

you'll need an opaque aluminum bag.

I'll discuss the differences between the two measurements

in a moment.

You will also need a few other items, including a sharp razor

blade, a magnifying glass, and, of course, paper and pencil

to record the information.

So the best time of the day to make a measurement

is at midday, usually between 12:30 and 2:00 PM.

And this is also called solar noon.

This is the time when the sun is the highest in the sky

and when the plants are most stressed for water.

It's also the time when the water potential value

is changing very slowly.

Selecting a Vine

When you're ready to make the measurement,

you should select vines that are representative

of all vines in the block.

Avoid using vines that are growing at row ends,

end rows, or vines that are overly weak, too vigorous,

or that are diseased.

Once you've chosen your vine, you

must decide what kind of measurement you want to make,

leaf water potential or stem water potential.

Both measurements are highly correlated to each other.

And both give you an idea of the vine's water status or,

in other words, how wet or dry the vine is.

Both measures are also highly correlated

to many other aspects of vine physiology.

So, in the end, you should choose the measure

that you feel most comfortable with.

Leaf vs Stem

Now don't let the name of these measurements fool

you, as both leaf and stem water potential measurements

use leaf samples.

The main difference between the two measurements

is how long the leaf is covered by the bag.

However, as I suggested, both are

very indicative of the plant's level of water stress.

Leaf water potential measurements

use leaf samples that are mature and fully sunlit

and are generally located in the middle of the shoot.

The technique requires bagging the leaf

with a plastic bag just prior to excision from the plant.

Leaf water potential measurements

are quicker to make.

But they are potentially more prone

to operator error compared to stem

water potential measurements.

Stem water potential measurements

use the same kind of leaf samples

as for leaf water potential.

However, the technique requires bagging

the leaf with an opaque Mylar bag

at least 30 minutes before sampling.

Bagging the leaf stops transpiration,

allowing the leaf's water potential

to come into equilibrium with the water

potential of the stem, hence, the name of the measurement.

Stem water potential measurements

tend to be less variable between operators.

But they require more time to make a measurement.

And sometimes it can be difficult to locate

the pre-bagged leaves in the vineyard.

Selecting a Sample

So, to measure leaf water potential,

you want to choose a leaf sample that's

fully expanded and mature and located

about in the middle of the canopy and exposed to the sun,

like this one here.

You also want to make sure that the leaf

sample is free from any sort of damage or disease.

For stem water potential measurements,

you want to have the sample be the same kind as for leaf water

potential.

But you want to make sure that it's bagged

prior to the measurement.

And we've already selected and pre-bagged one right here.

Note that the technique is the same for both measurements.

The only difference is how long the leaf

is bagged before you measure.

Once you're ready to make a measurement,

bag the leaf and use the razor blade

to cut the leaf off of the shoot,

leaving as much petiole tissue as possible attached

to the leaf.

Next, bring the bagged leaf to the instrument immediately.

Put the bagged leaf into the chamber lid

so that the petiole only protrudes about half an inch

and tighten the compression screw.

Then carefully put the bagged leaf in the chamber

and lock down the lid.

Open the control valve to the chamber position

and slowly open the rate valve to let gas into the chamber.

Note the pressure gauge showing the increase

in chamber pressure.

As you increase the pressure, use the magnifying glass

to view the cut surface of the petiole.

Making a Measurement

Close the chamber valve at the first sign of water

appearing at the cut surface.

This is called the endpoint.

Record the pressure shown on the chamber gauge.

To get an accurate reading, it is

important to increase the pressure slowly so you do not

overshoot the endpoint.

Using the rate valve, increase the pressure

at about one bar per second until you

get within two bars of the endpoint.

Then increase at half a bar per second

until the endpoint is reached.

After you've made a few measurements,

you'll get a feel for where the endpoint is

and get a sense of when you're within two bars.

Before taking any official readings,

practice with a few dummy leaves first.

Also, because the operator can be the largest source of error,

it's advisable to have a dedicated operator making

measurements if possible.

Now let's discuss some potential errors and problems

when making a measurement.

One of the largest sources of error in leaf water

potential measurement results from not bagging the leaf prior

to removal from the plant.

When the leaf is removed from the plant,

it loses water very quickly.

And that can affect your reading.

In addition, when the leaf is placed into the pressure

chamber, it is heated during pressurization, which

can also affect the reading.

Removing the Leaf

It's important to make the measurement rapidly yet

precisely.

As I just said, the leaf can lose water quickly

once you remove it from the vine.

For that reason, it's important to remove the leaf within two

seconds of bagging and to pressurize it

within 15 seconds of removal from the vine.

For this reason, it's important to not collect

a bunch of samples and bring them back to your truck,

but rather to bring the instrument with you

into the field.

And an ATV or some sort of farm vehicle can help you do that.

Broken Leaf

Sometimes the leaf can be broken when

it is put into the chamber.

And, when pressure is applied, air

is forced through the water in the xylem

and causes bubbling at the cut surface.

This can make it difficult to detect the endpoint.

If this happens, you can stop the pressurization

and exhaust the chamber immediately,

which will cause the sap to return into the leaf.

Then dry the cut surface with a dry cloth or Q-tip

and restart the pressurization.

If making leaf water potential measurements, as opposed

to stem water potential, where you

have to wait for equilibration, it's

better to just get another leaf sample.

If the bubbling starts again with your original sample,

you are likely at or have missed the endpoint.

Remember, at the correct endpoint,

the xylem sap should just wet the cut surface

and not form a lens or hemisphere of water.

The importance of slowly reaching the endpoint cannot be

overemphasized.

Cut End

The appearance of non-xylem water at the cut end

also can make it difficult for you to detect the endpoint.

This may occur when you are tightening

the seal on the chamber lid and accidentally

squeeze the petiole, causing water

from the outside of the xylem to be forced out.

For this reason, it's important not to overtighten the seal

around the petiole.

In addition, keep as much of the petiole inside the chamber

as possible.

Leave only enough tissue outside of the chamber

so that you can see the cut surface.

Leaf Anatomy

It also helps to be familiar with the basics of leaf anatomy

so that you can be sure the water you see

is coming out of the xylem and not the phloem.

Luckily, grapevines have large and easy to distinguish

vessels.

And they also don't exude any resins.

So it's easy to pick out the xylem from other tissues.

Finally, only use compressed nitrogen

to make measurements, not air or CO2, which

can affect leaf physiology and confound the water potential

value.

Make sure your gaskets and grommets are in good condition

to make the seal, both at the petiole

and at the chamber lid itself.

In general, it's good practice to have your pressure

chamber professionally recalibrated

before each field season.

How Many Measurements

So the question is how many measurements

should you make per vine?

When you're first starting out, it's

a good idea to make about a couple

of measurements for each vine.

If the two measurements are within about a bar

of each other, then you can move on.

If they're not within a bar of each other,

then it's good to make a third measurement for that vine.

And then the question becomes how many measurements do

you make per irrigation block?

It's a good idea to choose about three

to five representative vines for that irrigation block.

And then, once you get a good idea

of the water status of those vines,

then you can move on to the next block.

So let's see what this process looks like in real time

from start to finish.

Additional Tips

Here are some additional tips with interpreting

the measurements.

Leaf water potential measurements

give you lower, or more negative,

values than stem water potential measurements,

usually by about one to two bars.

Leaf water potential values higher, or less negative,

than negative 10 bars are considered non-stressed.

Between negative 10 and negative 12

is considered mild stress, between negative 12

and negative 14, moderate stress.

And negative 14 or lower is considered severe stress.

Stem water potential values higher than minus 8 bars

are considered non-stressed.

Between minus 8 and minus 10 are mild stress.

Between minus 10 and minus 12 are moderate stress.

And minus 12 or lower is considered severe stress.

Outro

Thanks for watching, everyone.

And, if you have questions about any of these techniques,

please visit our website site at owri.oregonstate.edu, where

you can find my contact details as well as

a bunch of other information related to viticulture.

Thank you.

Step by step instruction on how to use a pressure chamber as a tool to help you schedule irrigation in wine grape vineyards. Dr. Alexander Levin walks through the steps of using a pressure chamber to measure leaf water potential and stem water potential. Part 2 of 2 Oregon Wine Research Institute

Catalog - PNW 713