With another long, wet spring on the horizon for the Pacific Northwest, particular attention should be paid to wet spring soils. As rainfall continues, rivers swell and fields are saturated well into estimated production start dates.

It may be tempting to go ahead and cultivate fields or open up pastures. In these conditions, however, the potential damage to the soil far outweighs the benefits of an earlier start to the season.

Ponding

At the most basic level, soils are composed of mineral particles (sand, silt and clay). Pore spaces separate these particles. Pores are filled with a dynamic balance of air and water. Both of these are necessary for soil life, including plant roots and soil biota.

Large amounts of rain or irrigation water over a short period of time can fill pore spaces and exceed the water-holding capacity of the soil. This condition is known as field capacity.

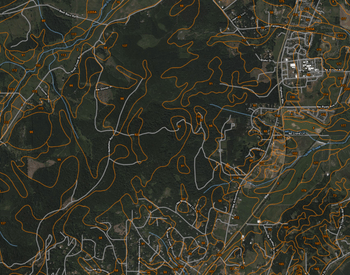

Under this condition, excess water cannot enter the soil, so it runs off the surface. This runoff from local topographic high points can lead to erosion across bare soils. The result can be rills, gullies and ponding in topographic low areas.

Soil type and drainage rate also affect runoff and ponding.

- Finer textured soils with more clay have greater water-holding capacity. However, they can also have slower drainage rates, which results in more surface water.

- Coarse, sandier soils have less water-holding capacity. As a result, they drain more quickly and remain saturated for shorter periods of time.

Compacted soils have less pore space and lower drainage rates. Thus, they have more ponding and runoff than do less compacted soils.

Observations during and after heavy rainfall events can shed light on variations in soil type and condition across the farm. Ponded areas may highlight management problems that lead to increased compaction. In other cases, they may simply reveal areas to avoid for a longer time following rainfall events.

Watching the flow of water from higher to lower landscape positions also can indicate where bare soils pose more threats of erosion. In these areas, care should be taken to stabilize soils with vegetation or residues throughout the winter and early spring.

Water flow after a rainfall event also illustrates how irrigation water is carried by the field and pasture soil. This may explain variations in water availability and plant growth during irrigation season.

Plugging

Soil compaction is the most serious threat to wet soils. As soil pore space fills with water, pressure and weight on the soil surface force soil particles together. When this happens, soil pore space is reduced and plugged with finer soil particles.

Clay soils are more vulnerable to compaction, but sandy soils can also be susceptible given improper management. A soil does not have to be completely saturated to be vulnerable to compaction.

Plugging reduces the water-holding capacity and drainage rate of a soil. It also reduces the diffusion and availability of oxygen and nutrients to plant roots and soil microbes.

Compaction is shown to reduce yields due to its effects on plant root growth. Across a field, the availability of air and water, as well as yield variations, often are the result of differences in soil compaction.

The effects of compaction can be reduced by some management techniques. However, compaction is difficult to reverse.

The most obvious causes of compaction are heavy machinery and tillage implements. High animal traffic can also lead to compacted trails or areas around feed or watering troughs. The result is a reduction in available forage. When a soil is moist, the effects of these practices on soil compaction are even more pronounced.

Checking the moisture conditions of your soil before cultivating will pay off in the long run. Determining soil moisture by feel is really more of an art than a science.

As a general rule, soils are too moist for cultivation if they fail the ribbon test or the ball test.

- For the ribbon test, push the soil between your thumb and forefinger. If the ribbon breaks before 1 to 2 inches, there is less risk of compaction. If a ribbon extends for 4 to 5 inches, the soil is too wet for cultivation.

- For the ball test, form the soil into a 2-inch ball. If the ball holds together when thrown into the air, it is too moist for cultivation.

Soil moisture probes are also available to help determine when the soil water content is too high for cultivation.

The importance of not cultivating a wet soil cannot be overemphasized. When in doubt, wait a day or two to reduce the risk of damaging the structure of your soil.

Pugging

Pugging occurs when animal hooves break through the soil surface. Wet soils are extremely susceptible to pugging because the soil surface is less stable when saturated.

Pugging can bury or uproot pasture plants. Localized compaction also occurs and further reduces pasture productivity.

Pugging damage can decrease pasture productivity from 20 to 80% during the year after the damage occurs. Yields can be reduced by up to 20% even after pastures seem to have recovered.

With pugging, a pasture surface becomes more uneven. This reduces forage utilization by animals. Additionally, weedy species are better able to compete with desired pasture species after pugging damage.

To avoid pugging, it is important to recognize the moisture condition of pasture soils. Under very wet conditions, it may be advisable to keep animals off pastures entirely.

Other options include moving electric fences more frequently or increasing the paddock area. Hardening high-traffic areas can also improve conditions for animals.

Timing is an important factor in preventing pasture pugging because the resiliency of a pasture is affected by its vegetative cover. Bare soils are more susceptible to pugging. The strength of grass roots increases with new pasture growth in the spring. This factor is an important consideration in timing turning animals out in pasture.

Seasonal variations in rainfall and the previous year’s grazing affect the strength of pasture roots. Thus, there is no definitive time to let animals out on pasture.

The best rule of thumb is to perform a pull test on your pasture plants. If they are easily uprooted by pulling, they are probably too fragile for grazing. If grazed too soon, the resulting bare patches will be more susceptible to pugging in the event of spring rains.

Conclusion

Watching the water on your landscape during a long, wet spring offers insights into differences in soil and topography. It also can help you identify management challenges and opportunities.

Wet pastures and fields are extremely susceptible to damage from compaction due to animals and machinery. In addition, pugging can reduce pasture productivity.

Appropriate timing of spring cultivation and grazing under wet conditions is essential. The goal should be to preserve long-term soil productivity and prevent the need for costly remediation efforts.