Transcript

00:00 Patty Skinkis

This is the HiRes Vineyard Nutrition Podcast series, devoted to helping the grape and wine industry understand more about how to monitor and manage vineyard health through grapevine nutrition research. I am your host, Dr. Patty Skinkis, Professor and Viticulture Extension Specialist at Oregon State University.

00:21 Patty Skinkis

A major part of monitoring vineyard nutrition requires that we collect tissue samples that are analyzed and interpreted for nutrient concentrations. Leaf samples are collected at either bloom or veraison, or both. We had several episodes last season that discussed the merits of tissue sampling, and in this season's episode we return to that question about sampling, but this time from the standpoint of whether those are the best times to sample and how those results may fit into what the grapevine’s nutrient budget is for a given season. With us today is Dr. Nataliya Scherbatyuk, a post-doctoral researcher working in the Keller Lab at Washington State University. She's been working on a project over the past few years to optimize tissue sampling protocols and to determine the amount of nutrients removed at the end of the growing season so that we know what's being recycled back into the vine and what's not. Nataliya conducted field trials since 2021 in commercial vineyard blocks where they're manipulating both potassium and nitrogen and then looking at how those have affected the time the tissue samples, in terms of their concentrations, along different time points that they measured throughout the growing season. And I'm really excited to hear her talk about this work because I think it'll provide a lot of insights into how we will monitor and manage nutrient budgets in a vineyard and it's a critical component of any fertility program. Thank you for joining us today, Nataliya.

01:49 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

Thank you. It's my pleasure to be here.

01:51 Patty Skinkis

It's really exciting in the second season to jump into the details of some of the research projects and get a better understanding of what goes on when we, as researchers, do some of these trials to see what is going to work better. I want you to tell us a little bit about how you got started on this research and the main research questions you're trying to tackle through the project.

02:15 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

Thank you for your question, and it's a very interesting question because plant nutrition is something that I was always interested about and I've done a PhD at [Dr. Markus] Keller’s Lab, and I worked on the water movement, and when I had a chance to work with plant nutrition, I was like, “Yes, finally I can do it.” So, as it's been already discussed in previous episode--and who did not hear that go back and listen to previous episodes--they are super interesting. We focused in on the main criteria, so, vineyard nutrition, and the main goal is to set up some sort of sensor tools that can monitor nutrition in the vineyard. My part of this project is tiny. It's a baseline. It's basically to re-evaluate the existing sampling protocols. It's great that you mentioned in the beginning today that we have different types of sampling. So, we can sample leaves at bloom and veriason, and by leaves, that's also an interesting question because we can sample either leaf blades or petioles, or both as a whole leaf. So, all of these questions make a big point: so what actually is the best sample? Do we sample at a specific time as we did it before and do we sample the specific material tissue the way we are doing right now. So we are testing existing protocols by sampling these tissues at bloom and veriason, but also we do sample additional tissues like canes which are dormant canes, shoots, for the leaves we actually separated in the blades and petioles. So, we sample separately blades and petioles and analyze them separately. We also sample berries at lag phase and harvest, and even the whole leaves at senescence.

04:10 Patty Skinkis

So, it's great to hear that other tissues have been sampled because that's often times a question I get from growers. “Why can't we use something else?” Especially if they see something odd at a different time of growing season, like early season. You mentioned using leaves and fruit and dormant canes. How about small shoots during the shoot thinning process? Was that a time point that you considered?

04:33 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

Yes, well exactly. It's a good point because if we find a way to sample something sooner than what we have been doing for long period of time, like shoots or canes, and if we can correlate that analysis to what we already know, we can predict the nutrition of the vineyard of the growing season. And why is this important? For example, right now when the sample leaves at bloom or veraison, and if we do find something which is not let’s say nutritionally speaking, not what we want to see in our vineyard, we might not have enough time to adjust any nutrition until the next season. But if we can figure out something from the beginning of the season, we still have a chance to adjust nutrients of the same growing season. So, there's something that my tiny bit of project was focusing on. And, in addition to dormant canes, we've been sampling shoots at five-six leaf stage. So, this is about the same time when growers go ahead and thin the shoots, and it makes total sense and it's very convenient because there is another thing that we need to remember, that the best job being done in the vineyard, is when it's convenient and not too expensive for the grower. So for them, for example, to go and sample leaves at bloom or veraison or both, it's quite time consuming, right? And then also expensive to send it out to the lab and then they’re waiting for several weeks to get the results and then those results come in and it's too late to adjust, so they can use that data to adjust for the next season. But if they can sample early in the season, let's say shoots, and then they are going to thin anyway, right? So, they just go to pick up the shoots they just thinned, prepare them for the lab and send them out, and if they can get the results from those shoots and we can correlate that to what we already know, they would be able to adjust nutrition that they need for this current season.

06:25 Patty Skinkis

So, you tested all those different time points and those different tissues. Can you tell us a little bit about how you did those? It sounds like you were working in a couple different commercial vineyards and there were different fertilizer programs going on. How were those collected when you did collect them? Were they kind of in small sections or large areas? Can you tell us a little bit about that?

06:48 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

Yes, of course. So, what we are working on-- we have three trials in commercial vineyard with Chardonnay, Syrah and Sauvignon Blanc and that's in Ste. Michelle [vineyards], and also, we have a Concord vineyard, which is juice grapes, in private vineyard here locally. So, for this specifically, when I'm talking about shoots that we analyzed, we basically went to the field and checked the leaf number on the shoots and we were waiting for the time when it's between 5 to 6 leaves. It is not a big deal, it's pretty easy to count the leaves. But another helpful thing for the wine grapes is that we are very collaborative in the commercial vineyard management team. So what I did, I was basically constantly in communication with them about when they were planning to do shoot thinning, so as much as possible I could overlap some places when growers were going to shoot thin. So let me sample the shoots at the same time and see how convenient that would be for the growers while they are thinning and doing that. Also, as you mentioned, we do have different fertilization treatments. We are having potassium in Chardonnay where basically we are applying three different potassium rates, and the rest is nitrogen trials with the different grapes of Sauvignon Blanc, Syrah and Concord. Each treatment has its own data vines, so the best way of course, it to focus on the data vines and constantly coming back to the same vines throughout the season. So, if I was sampling canes from my data vines, then I would come back and sample shoots and leaves, berries and all of that throughout the season, so I knew what vine exactly it was.

08:34 Patty Skinkis

And you think those data vines allows you to also correlate to other measures that you would have collected during the season? So, kind of smaller scale sampling just for the definity of the data?

08:46 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

Absolutely. Yes, and it's a good point that you just mentioned about the correlation because at the same time we have a team of smart engineers from CPAS (from WSU), and when I'm collecting my shoots at the stage of five-six leaves at the same time they come in behind and they’re taking pictures of the vine, of their shoots, and they doing that for also leaves at bloom and leaves at veraison. So, the whole idea is here to see what we find on nutrition perspective from our tissue analysis and what they find from spectral analysis and see we can find any correlation between our data and their data and a way we can get closer to those sensor tools that I spoke in the beginning of the podcast.

09:29 Patty Skinkis

Yeah, so the goal would be that what we see in the fine data matches what they can sense in those sensors, and that's always the nervousness is--do they both align? You know, the best signal may not be when we see the biggest impact on the nutrition.

09:43 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

It is, and then plants are resilient. Sometimes it seems like it's easy but plants find a way, have to survive under extreme conditions and we not even notice that. So yes, it's a quite interesting project.

09:54 Patty Skinkis

So, what have you found so far? It sounds like you have three growing seasons of data?

10:00 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

So, the way project started, it was in the beginning of the season actually so the very first year we didn't have any chance to collect any early tissues of the season. So, the third season for the tissue collection will be actually this season (2023). It's about few months we will be going ahead with the shoots. It was quite interesting to see, for example, that it was slight correlation but positive correlation between shoots (5-6 leaf stage) and petioles at bloom and some blades at bloom, and by some I mean it depends on the variety. But what was interesting to see that exactly those shoots were correlated with petioles at bloom or blades at bloom. And of course, we can't draw any conclusion just yet because we need to repeat some of the tissues are still, like I like to call them, “they are still in the bag.” So, we still need to prepare them, grind them and send them to the lab to analyze them [the nutrients] and then analyze the data. It's quite time consuming to do it, but it was quite promising to see that correlation between shoots and the tissues because until now that's what we've been doing, it's leaves at bloom and veraison.

11:13 Patty Skinkis

You had said that there you see some differences between the varieties? Is that something, I mean, that that's one of the pieces of this this project that we presumed was the case. That there is going to be variety differences, possibly rootstock differences, and in what the nutrient tissue kind concentration is and do you see anything so far that's very clearly becoming a variety story in terms of what timing their concentration seemed to be impacted?

11:42 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

Not clearly in that way. So, for example, what I meant is when I was correlating shoots and leaf tissues at bloom for Chardonnay for example, there was a positive correlation for potassium between shoots and blades at bloom. I believe that's what it was. While for Syrah it was petioles at bloom, so it's not necessarily that I can say this Syrah is very different from Chardonnay, but those tiny bit of correlation difference is still where a tissue of the leaf at bloom. But in one case, there was blades at bloom, one case there was petals at bloom. But again, it's too early to say there was a difference because there was only one year of data and we need to repeat it several years to see.

12:29 Patty Skinkis

Yes, all of this always we look for those patterns over multiple seasons and why it's so critical to keep going with this kind of research instead of just doing once and done. So that's completely understandable.

So, with the fruit, so that's been another time point that a lot of growers are cutting fruit off, at least here in Oregon, during the lag phase, and they've often asked this question. I mean, not a lot of growers, a few inquisitive growers have asked, “Could we just measure this fruit we just cut off? It's just desiccating on the ground, could we measure that to get a good snapshot of what we're expecting to see, perhaps as a predictor for harvest?” Maybe for YAN or other nitrogen or maybe in potassium, if that's an area? Do you think that there's any potential there or have any insights from the work that you've done so far?

13:20 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

So, it's a fantastic question because I do feel like some fruit is just being laid on the ground with no reason and I didn't get any specific tips on the lag face fruit except I believe it was once that I saw a positive correlation between shoots and berries to lag phase, but I think it was only for one variety and it didn't repeat itself. So, this is something that I need to reanalyze for this coming year, and the data is supposed to be coming soon. We just finished grinding the berries at lag phase, so it should be analyzed pretty soon and see if there's any correlation. But it's a good point because if, for example, we can correlate shoot tissue nutrient analysis and predict berry [nutrition] at lag phase, we can also build up some story for a little bit ahead of time for the season. For the other part of the question that you've been asking about fruit at lag and YAN and all of that part, it's a fantastic question for our PhD student who is actually working on the YAN questions and wine-type of questions for that. So, if you do have a chance to interview Pierre Davadant, they would be great in the future. He might tell more about that. I'm focusing strictly on reevaluating samples, and a lot of sampling tissues and analyzing nutrients in the samples.

14:43 Patty Skinkis

And that's a really good point that all of this is being connected to, at least as much as possible, to the fruit end-product and also to wine, and so I know, luckily at WSU a lot of the wines are being made and fruit are being analyzed from both Oregon and Washington trials, and then in the east it's being analyzed by groups over there for more local project sites. So, there will be information coming on that.

So, you said they're going to have the third growing season in 2023. Are there any things that you are going to do differently this year that you're going to look at, or is it going to just be a replicate of those past years that will help confirm any patterns that you see in the data?

15:25 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

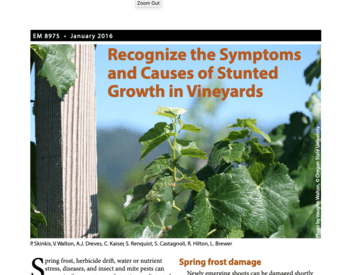

So, it will be a replica because it makes sense to repeat again to see if the correlation that we had in previous years will be repeating themselves again. Which, additionally, it's kind of important to mention that we are working on the same data vines so when we apply in different fertilization rates from previous years. It's interesting to see how they will affect current years as well because it's repetition for fertilization as well. Another thing which is quite interesting that I found and I haven't mentioned yet, but you did mention in the beginning, is the budgeting part, and that’s one of the most interesting for me. It's also interesting because there was not the planned work in the beginning of the project. But you know how it goes--we start something then we add additional [components], and it comes out quite interesting and we then repeat it. So, what part for that I've done is that at harvest when we collected fruit, when we harvested fruit for wine making purposes, we also analyzed nutrient analysis of that fruit just to see how much nutrients we can actually relocate or take out of the vineyard every growing season. But additionally to that, it was very interesting to see once that, I don't know about your location, but we do get a lot of winds, especially through September and November. Some days you can go home for your evening and the vineyard will be full of leaves and next morning there is no leaves. There are no leaves on the floor as leaves have moved out of your vineyard. So, the question that lays down is okay if those leaves do have nutrients still and those leaves have been blown away from your vineyards, are the nutrients being blown away as well? So that's quite interesting question because it brought up even more sub-questions to that. For example, if we do have beautiful senescence like past year or year before when we had all colors in the vineyard, it was beautiful, and we do know that during senescence the nutrients are relocating back to the permanent organs, and then next growing season those nutrients will be pushed back to the vines. But if we have those unexpected freeze sometime early in the season like September, even October when the leaves are still green, what's going on then? What happens then to those nutrients? So we’re assuming if the leaves are still green, the nutrients are still in the leaves, and nutrients haven't had enough time to recycle themselves back to the permanent organs. Now when we do have freeze and leaves are disconnected from the plant and on the ground, it means that those nutrients did not have a chance to be relocated to the permanent organs. If those leaves are still sticking around in your vineyard in the soil, it's probably good because at some point those leaves will be incorporated into the soil and nutrients at some time, not probably the next year, but this few years will be a chance for the plant to absorb those nutrients. But if you do get quite windy conditions and those leaves are being blown away to your neighborhood, it means you're losing quite a bit of nutrients out of the field, depending on when a freeze event happened. It’s quite interesting for me to actually figure out that for example, on average, between our four varieties and those three wine grapes and juice grapes, we can lose about eight pounds of nitrogen per acre and that’s just with leaves, we’re not talking about the fruit--just the leaves. Or for example, one pound of phosphorus, three pounds of potassium. And that might sound not that much, but if you think about how many acres you have in the vineyard and if the freeze happened early in the season, it's even more nutrients coming out. It might be not a big problem if you're talking from this growing season to next growing season, but if we don't think about that ahead of time for long term we do potentially, can face nutrient deficiency with time.

Plus, we do remove a lot of nutrients with the fruit. So just in average numbers, for example, we can say that per acre overall on average we can lose about twenty pounds of nitrogen per acre, and I'm talking with fruit removal and leaves. And that's if we assume that our yield was five tons per acre and sometimes can go higher and if you think about juice grapes when we have about ten tons per acre of yield, so it's even more. It can be up to 35 or so pounds of nitrogen per acre. So there's something quite important for us to remember when we plan the fertilization program for the next season to incorporate in that fertilization plan. Quite important, quite interesting. You know it's like so where are you leaves? I remember once, my advisor Dr. Keller--he sent me the picture and I was looking the picture I was like, “What does it mean? I mean it’s just a picture of leaves on the ground,” and then a few seconds later, yeah, I understood that there was senescent leaves from the vineyard and but they were in alfalfa fields, so clearly the whole leaves had been blown away. So, it means all that new nutrition went to somebody else and not in our nutrient [pool].

21:11 Patty Skinkis

So, during the project did you have any early freeze events that you could work with in that budget? Or is this something that you could potentially mimic in the future to try to see what a freeze event does to the actual budget?

21:25 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

Yeah, that was a good point. So basically, when I started the very first year, I believe it was fall 2020, we had quite early freeze and it was unplanned part of the project. But I don't know how that happened that I went ahead and I covered a few vines so we do have some leaf collection from that freeze event. Then we had the beautiful Fall of 2021 where our senescence was gorgeous, and freeze didn't happen until I believe in November. I just don't remember the dates exactly, but if you remember how beautiful it was in the orchards and in the vineyards. So yes, we do have naturally different freeze events that happen, and we can see it in the data as well. We can see the nutrient content difference between the years and that's great because you immediately try to see what was different during that year. But also mimicking question, it's quite interesting. We thought about that, we didn't set it up yet, it's time consuming. I wish we have another student or intern for a little bit more time but that's something when we do get great data to explore and continue. It's another question is to mimic and see what actually is being left in the field, in those leaves when freeze happens in different time.

22:47 Patty Skinkis

Yeah, that would be very interesting to see but I understand just how difficult that can be to try to orchestrate that. I want to go back to one of the tissues you said you used was dormant canes. Now I know Paul Schreiner's group has looked at dormant canes a little bit. Never published anything yet about that, but did you find anything useful? Or was the content or concentration just so low in dormant canes?

23:11 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

It's a good point that there is no wonder why Paul Schreiner has a hard time publishing anything because it's not that it's not useful, but canes itself is a little bit pain of working with. So, you're asking yourself a question: How do you collect dormant canes? What I did, I basically separated internodes and nodes and then of course I was like did I need to do it? Because every internode length is different basically for the varieties and then you’re becoming, you’re basically putting yourself in one question: was it too long? Was it too short? Was it in the middle? Was it, you know if what I was trying to see if there is a correlation between internodes and nodes and I didn't find any, so if there is no correlation, what do you suggest to growers to collect--just the canes or just internodes or nodes? So, I didn't get anything useful but another trick about canes that the material is so hard that I didn't have a good way of how to grind it. Because you do know, that the material has to be dried out and then ground and we just not too long ago finally found the proper machine that they grind the material. So basically, at this season I'll try to go ahead and have all the canes ground up and then analyze the data. So, more data should be coming closer to the end of the season to make any conclusions for the canes.

24:38 Patty Skinkis

And was there a certain time point that you targeted for the dormant cane selection? What time during the dormant period?

25:46 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

We usually do it sometime in February when we do our pruning, and again, this is a good point to remind that we try to collaborate with growers as much as we can. So, when we talk about wine grapes, they try to see when they going to prune that specific blocks that I'm working with. So, for example, the blocks that I'll be working with, my Chardonnay, Syrah and Sauvignon Blanc, they are planning to prune sometime the end of February-beginning of March. So, the plan for me is to have my pruning weights and samples done by the end of February, so that way I can say that the really overlappping was what commercial vineyard does.

25:27 Patty Skinkis

It's one of those things that you know we have a time a window of time when it's less pressing. It'd be nice to be able to get several different samples, but it is the tricky thing of not necessarily having it relate well to what's actually coming out in the nutrient kind of budget, of what's going on in the grapevine.

25:45 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

It is tricky. It is very time consuming and also time consuming to work on the tissues after we take our samples, but it's also very expensive to send it all to the lab and have them analyzed. And when we speak about data vines, we do want to have statistically well-represented sample amounts, so we want to go statistically proper way. So, we have tons of samples and you really need to pick and choose which ones to have it done. And financial perspectives as well, so we can build the proper story.

26:20 Patty Skinkis

I think that's a good component of our conversation that I want to come out to the listeners is the fact that something very simple can take a long time, and just sampling in particular. I think especially for growers we think, “Okay, we have a sample we can take, a test we can do, then we get an answer.” But we know that's not always the case. So when you do research onto the methods like this, it's a small part but one of the most critical parts of doing this kind of research. So that when we're getting a sample it's not like when a grower gets one sample per block. We're getting hundreds of samples at a given time point. So why it takes so long to handle that tissue sample and then store it and archive it and then finally get it to the lab, whether it's internal to the institution or if you have to send it away. And just for those of you out there who think we can just do all this for free, we can't; often times we're paying full price for the labs to do the analysis, too, if we don't have a ICP or C&N analyzer in our in our labs. So, it's a lot of work and I'm glad you're working on this project. I know that there's a lot of good potential coming out of this work and I'm glad that's it's being undertaken.

27:38 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

You brought a very, very, very important point when you've been discussing. You said the growers, they had taken one sample per block and this is another thing why we focused in on this re-evaluation of these existing protocols is not the only the fact that protocols itself, they've been created back in sixties (1960’s) and eighties (1980’s) when deficit irrigation hasn't been introduced, and we know that for example in Washington we are heavily on dependent deficit irrigation. Deficit irrigation does affect the nutrient absorption, right? So, we have that. But another thing why it's important to create a new sensor tools and but before creating any sensor tools to retest all that ground truth data is for example, when we end up taking only one sample, and it doesn't matter how many leaves you're going to take, it can be 50 leaves, 100 or 200 leaves. But if we combine all of those leaves in one sample and we analyze that and we have one number, it will never cover the special variability [of the land area]. If you do have, if you have your block, let's say of five acres but there is the one spot there, just different from the rest, if you don't focus separately on that one spot of your vineyard it’s just going to be scrambled, everything in one result. So, you will treat the whole block as average, and you will never focus on that one spot. That's why we’re trying to make it as variable as possible to cover those spots and see how that affects the nutritional situation of your blocks.

29:14 Patty Skinkis

That’s a good point. There's some research where we want variability and we want to exploit that variability to understand the relationship, so that's excellent. So, I wanted to ask you a question. How did you get started in viticulture research?

29:31 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

Fantastic question because, you know, I have a long, long background with overall horticulture. I went to university back in Ukraine, and my bachelor was with potatoes. Then my masters was with potatoes, and it was all focused on genetics of potatoes. Then I had a chance to be in an international program in Germany at Humboldt University, but the focus there was ornamental plants. I always loved ornamental plants, that hasn't changed. But the whole point what I'm trying to say, there was potato, ornamental plants, then I even had several courses to properly store grains, which is quite different. I did a few scholarships in Europe for ornamental plants and vegetables, and then I ended up doing my internship with the Tree Fruit Commission in Washington, and I was heavily focused on tree fruit. It's apples, cherries and pears, and at the time when I was doing my internship, it was a year of internship, I got to know about WSU a lot. And during the time they sent out a few emails, and one of my emails was from Marcus Keller, and of course nothing worked out in the time when I when I was planning. But later Marcus Keller connected with me back saying that he had this opportunity for a PhD student for viticulture and I was like, okay. Viticulture is new. So that's how I ended up being with grapes and clearly no regret here, I'm still with grapes, I love grapes. I do like grapes as a plant; I'm not so much into wine itself, but I love plants. I really like the grape as a plant, and it is just a resilient plant. We always like to joke in our lab that those are probably the most resilient plants. It doesn't matter where you're going to throw the cutting, it’s just going to grow. It's not as easy as it sounds but it is very resilient.

31:29 Patty Skinkis

Well, that's great. The diversity in the background of horticultural crops you've worked on has certainly probably led to some different perspectives coming into the viticulture world.

So, I know you love plants and to wrap up with the fun question: What is your favorite plant of all time and why? And it doesn't have to be grapes just because this is a viticulture podcast.

31:54 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

It's quite a hard question I think for any horticulturist, and I did get my PhD in horticulture department, so I always say I'm a truly horticulturist because I don't have favorites. But I think the biggest trick that I can be bought on when we speak about plants, is the foliage. I really, really like something different about leaves, and there are cool grapes by the way, as well. Some grapes are very decorative, so whatever is big and different color on the leaves, those are my favorites. So, if we speak about houseplants, and that's something that I always have, I believe the family Araceae would be my favorite family. They are so diverse, and they are so foliage, just different foliage by size and colors and shapes. So that’s what I'm biased towards to. Flowers are great. Flowers, they’re beautiful, but I will still choose leaves over flowers and maybe that's why this you know reevaluation of sampling protocols is quite interesting for me because we sample so many leaves and some days I wish I don't, but it still goes back to beautiful leaves.

33:09 Patty Skinkis

Well, I can understand that completely because the leaves are there much longer for most plants. You know, flowering is only a small period of time. Although you know that can make it a special part of that plant. But yeah, it's as a fellow plant lover, I totally can understand the appreciation for canopies and the leaf shape and size and color.

Well, it's been a pleasure having you join us today and share some of your research with us. If you want to learn more about Nataliya's project and the HiRes Vineyard Nutrition Project overall, you can check out our website at https://highresvineyardnutrition.com/and follow us on Instagram, LinkedIn and X (formerly Twitter).

33:59 Nataliya Shcherbatyuk

Thank you so much, Patty

In this episode, we break the status quo and discuss alternative grapevine tissues being investigated for nutrient sampling. Dr. Nataliya Shcherbatyuk, post-doctoral researcher at Washington State University and the HiRes Team’s Project Manager, describes the research she conducted to understand the validity of other tissues in correlating with standard methods and how that project led to interesting findings about nutrient losses due to frosts and wind.